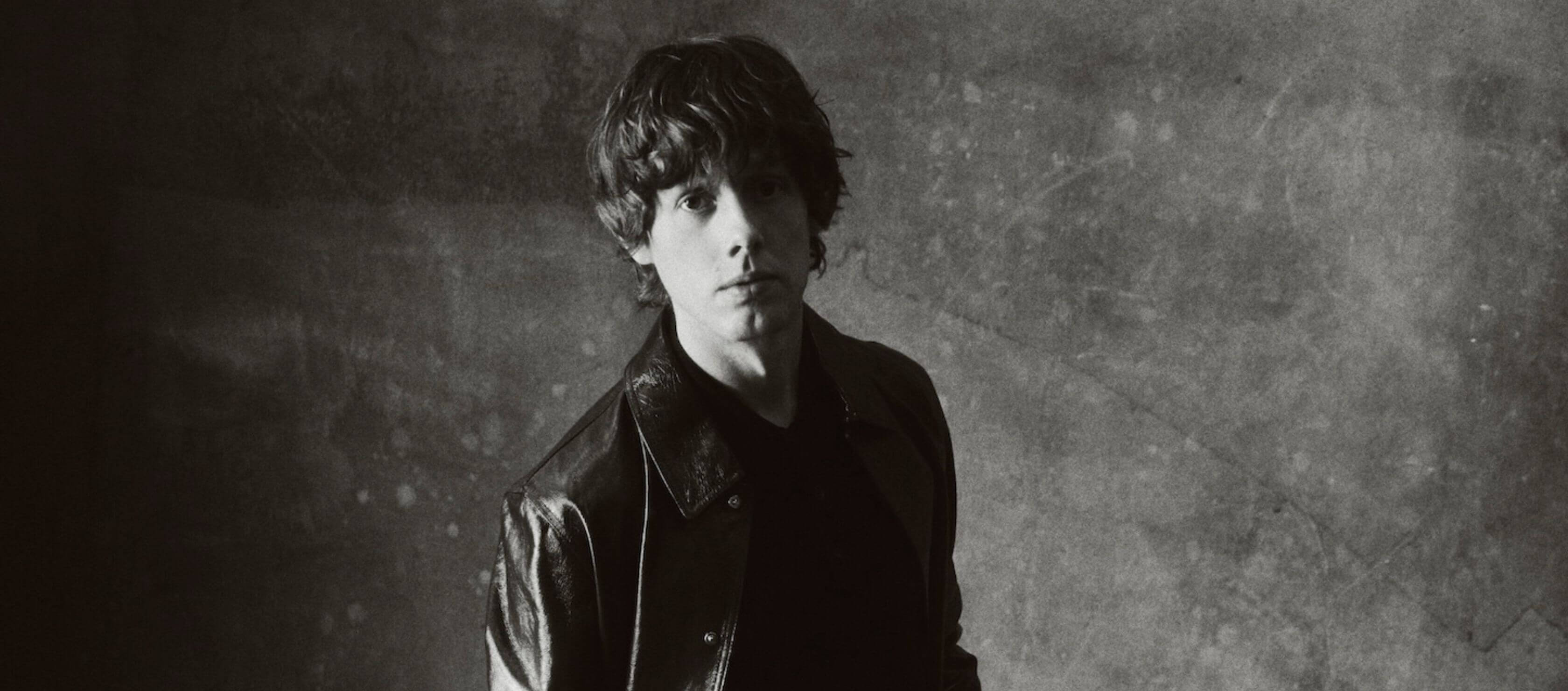

Davóne Tines is the Virginia-hailing bass-baritone countering his medium’s antiquated narratives – and fighting for its survival.

Classical music has long been a no-go area for younger audiences. And as those generations have grown up, the labels of ‘dull’ or ‘outdated’ have been known to linger. ‘It’s a beautiful but obsolete relic of a time long gone,’ kinder skeptics might say. But, actually, when you look beyond the generalisations, it’s a field of music in which some of the most striking and innovative contemporary art is currently flourishing – work that challenges the very notion of what creativity and classical music, itself, can be.

And at the top table, you might find Davóne Tines. A leading architect in the reconstruction of how operatic classical music sits in the cultural imagination. Born and raised in Virginia, Tines acquired a bachelor’s degree in sociology at Harvard University – his learnings and political ideas still rooted within his creative output – before exploring his true passion in music, interning at Cambridge’s American Repertory Theatre before studying a master’s in voice at Juilliard.

Fast forward to now, and the 38-year-old visionary boasts an eclectic and evolutionary portfolio, which spreads widely across concepts and sound palettes, from ROBESOИ – a 2024 debut record with his band THE TRUTH that explores Tines’ intrinsic bond with 20th century baritone and civil rights activist Paul Robeson – to premiering operas with some of today’s leading composers (Pulitzer Prize and Grammy-winner John Adams and current scene figurehead Matthew Aucoin).

Now, Tines lands on UK soil, enlisted by The Barbican to be their Artist in Residence from October 2025. As someone whose relationship with one of London’s most iconic cultural and creative spaces weaves through the tapestry of his career to-date, it’s a collaboration that feels seamless for the musician. “When I think about it, I realise I’ve been getting to know London and The Barbican for a decade now,” he says. “I’ve been lucky and privileged to have had some of my most formative musical experiences there which has led to other exciting things.”

The residency – on until February 2026 – will see Tines offer a trio of performances across the season, showcasing radical new works. He’ll be exploring, in a project curated by cellist Seth Parker Woods, the life and work of Julius Eastman, a pioneering gay, Black composer who revolutionised minimalism with classical theoretics in the 1970s. Elsewhere, he’ll join the BBC Symphony Orchestra and conductor Daniele Rustioni for ANTHEM, an exploration of American national pride in its past, present and future. And, finally, he’ll join Pulitzer Prize-winning conductor Tyshawn Sorey and other musicians in the Barbican’s canal-side St Giles Cripplegate Church for Monochromatic Light (Afterlife).

And to top it all off, THE TRUTH will return – with Tines currently working on a new record with the group amalgamating styles spanning alt-pop to Baltimore club beats and quiet R&B. It’s self-described as his “most universal project yet.” But, for now, The Barbican beckons and Tines is reflecting on his own journey, those nagging misconceptions of classical music, what Julius Eastman symbolises for him and why The Barbican’s Brutalist architecture feels like home.

Ben Tibbits: How did you first find yourself within this creative world? What initially drew you into it?

Davóne Tines: Looking back, I think I’ve always been fascinated by how creation has changed. In middle school, it was possible to touch a piano and change the vibe of the room. It was possible to play a violin in an orchestra and change the alchemy of the audience. In high school, it was possible to sing certain chords with my church and school choirs, which really helped calm my nervous system. In college, while studying sociology, I came to understand why art exists and how it influences and changes generations. I was hooked and had to expand my obsession with change beyond music.

BT: What do you think is the biggest modern misconception of opera and classical music?

DT: The biggest modern misconception of opera and classical music is how it misperceives itself. Somewhere in the middle of the 20th Century, these practices entered a ‘golden age’, helped in part by the modern industrial revolution, which flattened creation into the replicable – the optimised. It was the first pump of the brakes on a huge locomotive destined to lose momentum and come to a halt – the Titanic’s iceberg. Opera and classical music became museum temples too loved and sanctified to be questioned and rebuilt. Institutions have failed to encourage their wealthy, dying disciples to pass on the tenets of their worship and patronage to the progeny-cum-stewards of their migrating generational wealth.

Classical music and opera forgot that it had to entice its audience, rather than being overtly about them. Offering a continual invitation that meets people where they are, takes people to a place they didn’t know they needed.

BT: Congratulations on your artist residency at The Barbican this autumn! What’s your relationship with the space?

DT: I’ve always known The Barbican as a place of quality and adventurousness. It seems to have a special, authentic way of honouring the past and the future at the same time; something many, many institutions fail to attempt. In terms of the space, more literally, I’ve always had a love for Brutalism. The metro in Washington, DC, near where I grew up, had its own classical-brutalist style that still fascinates me. My home airport, Dulles in Virginia, to which I’ve travelled innumerable times, is also Brutalist, and its unique aesthetic has become associated with the idea of returning home for me. The Barbican is starting to feel that way, too.

BT: In the residency, you’ll be exploring the work of Julius Eastman. As a leading advocate for the revered composer, what makes his work so special to you?

DT: Eastman used the tools and context of classical music to bend the medium into an apparatus of his own singular and seminal expression. He reached that reality through the sheer power of his conviction to exist fully as himself at all times in all contexts. Existing this way is the personal thesis of my life. As a Black, gay triple-threat composer, pianist, and singer, naming his pieces things like “Evil N***”, “Crazy N***” and “Gay Guerrilla” – he asserted his identity in the concert hall by repurposing the words used to attack him. Under those titles, he wrote the most expansive, stunning, intimate, powerful, and revelatory music. In Berlin, we programmed solo Eastman a cappella works interspersed with movements of Beethoven’s most monumental work, the Missa Solemnis. The Eastman held up soaringly against the giant. I consider him an ancestor. I am endlessly inspired by him.

BT: How significant is pushing the boundaries of what classical music can be in the minds of the public?

DT: If the boundaries aren’t pushed, the zeitgeist will continue to divest and move on, and the art forms will sadly die a natural death. As one way to look at remedying this, I want artists to know it’s okay to be themselves all the time in everything they do. And to know that they’re not a cog in a machine, they can change the alchemy of the machine, by continually learning who they are and using their artistic output to articulate that ever-evolving truth. I want institutions to thoroughly support artists in this foremost task, and not in a patronising, reductive or lip-service way. That will require entire ideologies to fall and be rebuilt, not unlike the ideologies at odds in our current world. Forms of expression are meant to evolve. Otherwise extinction is nigh.

![Picture of “This Mixtape Is Kicking The Door Open To The [Tsatsamis] Project”: Tsatsamis Talks Tsycophant](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2FTsatsamis-Hero-export-768x335.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_HaJn5DvkMiR7b3yLhqRbLkCcwnHD)