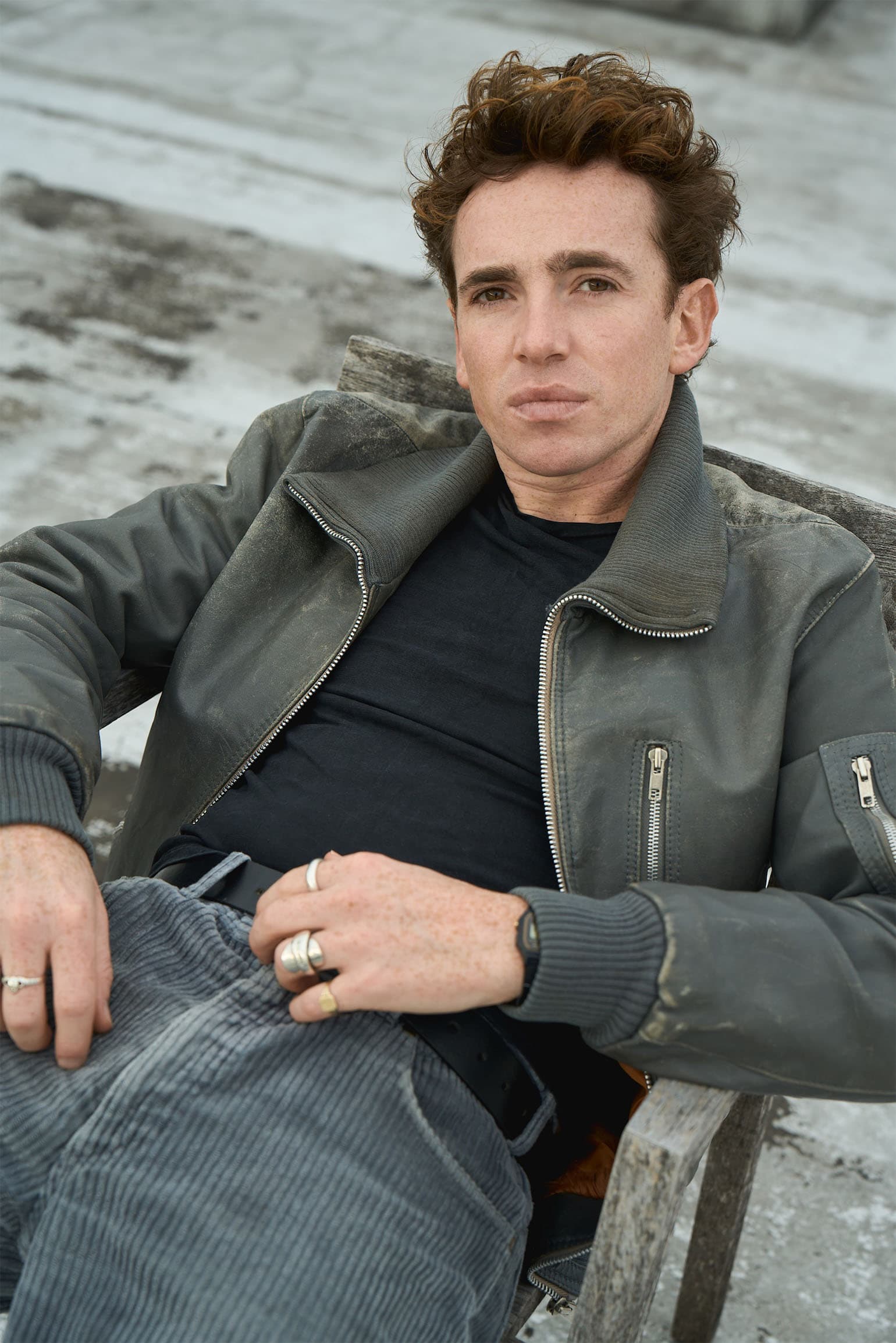

From gentle comedy Leonard & Hungry Paul to absurd indie mockumentary Lady and his upcoming National Theatre debut – the British actor’s enjoying a well-paced career high.

Laurie Kynaston finds, often, that people know his face, but they can’t quite place why. “The worst is when they say, ‘What do I know you from?’ And you list a few things, and they say, ‘No.’ ‘No.’ ‘No.’ And I feel like a twat by listing my CV,” he laughs.

That robust, thoroughly impressive CV has been amassed by the 31-year-old – across film, TV and theatre – since moving to London from his native North Wales. It’s been a somewhat piecemeal process. “[My career has] been a slow and steady race,” he says. “There’s been peaks and troughs.” There were early bit parts in the training ground of British continuing dramas (Casualty, Doctors), a young breakthrough moment, aged 21, in BBC comedy Cradle to Grave, and a turn alongside Brian Cox and Patricia Clarkson in the 2024 London revival of Long Day’s Journey Into Night. He’ll often deduce that it’s Harlan Coben’s suspense-laden thriller Fool Me Once that prompts people to approach him on the street, however. That show was watched for a total of 238 million hours on Netflix in the first seven days following its premiere in January 2024. “This very elderly man and his wife came up to me in a silent cathedral [in Spain] and took my hands and said, ‘Congratulations on the series,’” he says incredulously.

However, the fact that people struggle to recall their familiarity with Kynaston seems less reflective of a low profile, and more so the breadth of cultural contributions he’s made since he set up shop in the British capital 12 years ago. For him, the company of the industry’s most esteemed is customary, as is being tasked with his craft’s most storied repertoire and finding himself at the sharp end of stories unravelling new perspectives.

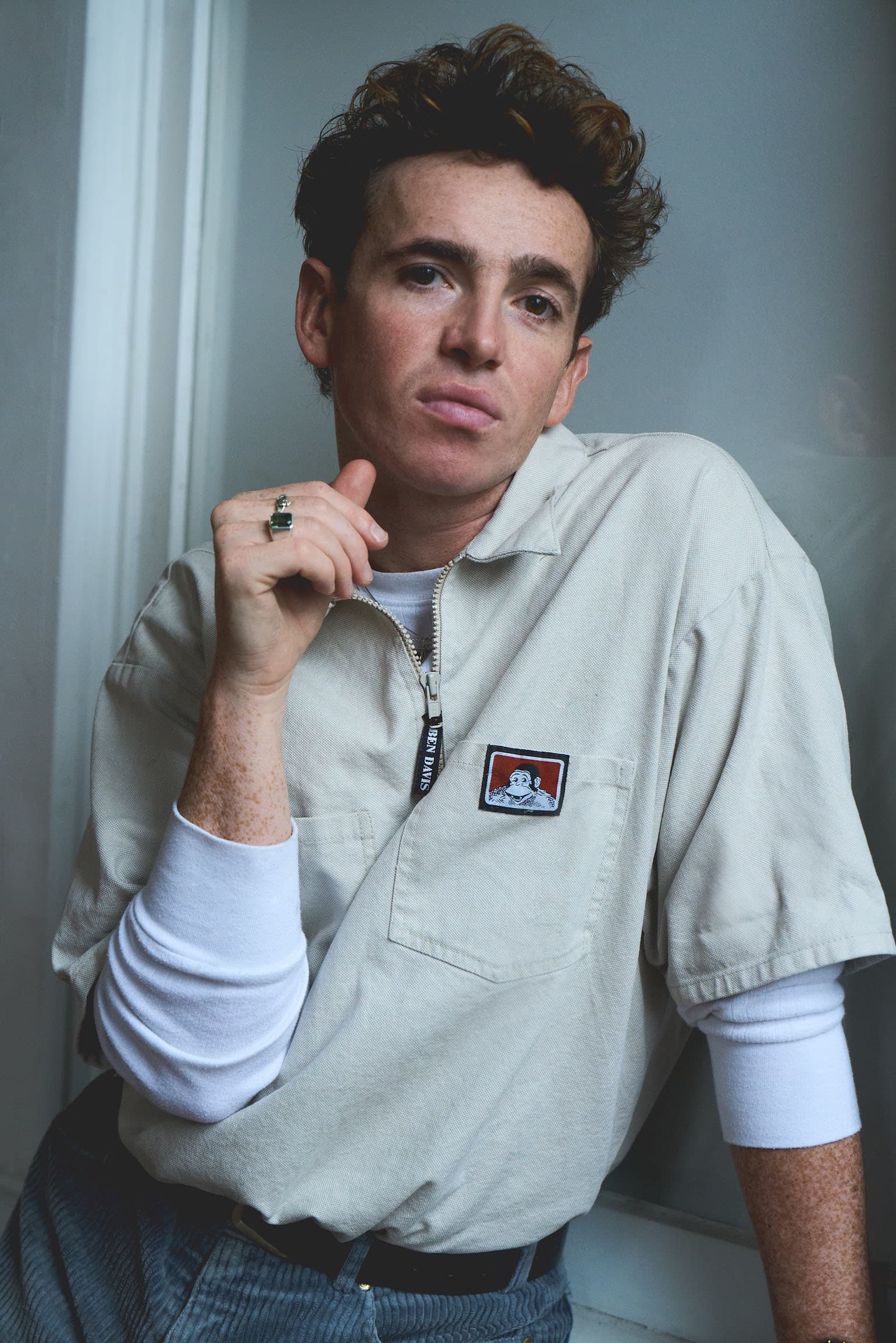

You just have to look at his current array of promotional talking points for a glimpse at that variety in action. When we meet on a November Thursday in East London’s Cat & Mutton – a Broadway Market watering hole with prestige to rival Roberts, Cox and Clarkson – it’s three weeks since Leonard & Hungry Paul’s release. The critically-beloved BBC adaptation of Rónán Hession’s 2019 novel sees Kynaston share a credits roll with Julia Roberts (the show’s narrator) and co-lead alongside The End of the F***ing World’s Alex Lawther. It has been embraced as “a warm hug” by a “world that needs it” if the reflections flooding Kynaston’s DMs are anything to go by.

We catch up on the afternoon preceding the final of one of the broadcaster’s other autumnal triumphs, The Celebrity Traitors. Kynaston, alongside 11 million other Brits, has been a faithful consumer; however, he darts back to his nearby home after our chat, as he missed the penultimate episode due to a loosely-termed research mission to New York. His upcoming stage return in Man and Boy was the cause of his field trip. The National Theatre’s take on Terence Rattigan’s account of the relationship turmoil between a 1930s financier and his estranged son Basil (Kynaston) is backdropped by The Great Depression and the Broadway and jazz the era played host to. “I was like, ‘While I have the time, I want to go and sit in as many bars in Greenwich as I can,’” Kynaston smiles. His trip was preceded by the London Film Festival premiere of the third entry in this career trifecta – flamboyant mockumentary Lady following, as Kynaston describes, a “nightmare, rude and flippant” fictional member of the British aristocracy, played by Fleabag’s Sian Clifford. Kynaston plays director Sam Abrahams (named after the feature’s real writer and director), who pitches up at Lady Isabella’s country estate to commit a fly-on-the-wall account of her existence to film.

The film was lapped up by critics in a similar fashion to Leonard & Hungry Paul. The latter was called “the perfect antidote to modern life,” in The Guardian’s four-star review. “I think people really get it,” Kynaston beams of the series. The comedy ambles along as a tender celebration of introversion, with modestly documented highs and lows for its titular characters – Kynaston’s Hungry Paul and Lawther’s Leonard – as they go about their innocuous existence in a Dublin suburb. Hungry Paul serves as a confidant for Leonard, not least in their weekly board game night, as Leonard embarks on a steady expansion of his horizons following the passing of his mother. “Hungry Paul just kind of lets his life flow like a gentle stream,” Kynaston says. “And that was a really lovely person to get to inhabit.” When he’s not completing his weekly postal shift, Hungry Paul’s weathering shifts in his own reality – the marriage of his sister, for example. And he’s almost always donning a buttoned-up shirt with an illustration-bearing piece of knitwear sat on top as he navigates.

As for his name, the character doesn’t seem to be wanting for food, and so the moniker is one aspect of his life that isn’t immediately untangled with a concrete rationale. “I just think it’s the thing in life where every family or every friendship group has an infamous story or a certain nickname they call somebody that has gone down in history and nobody really even knows why,” Kynaston says. “[My family] calls my Dad Alman, which is a kind of amalgamation of old man.” Even that gets shortened to Al by the family. “We would be like, ‘Have you spoken to Al?’” Kynaston’s father is called Steven.

Another feature of the show that prompts additional enquiry is, naturally, the presence of Julia Roberts. One might ask how the dulcet tones of the Hollywood luminary ended up draped over such a decisively un-Hollywood production? “It’s quite strange isn’t it?” Kynaston admits. As he explains, Roberts’ casting stemmed from her stumbling across the book in a shop, and reaching out to Hession after reading it to express her love. Roberts’ contributions were recorded over four hours in her San Francisco home, so Kynaston hasn’t come face-to-face with her yet. But the fact that she’s watched the scenes and, by dint of her participation, endorsed the work is enough. “It’s when she’s like, ‘Hungry Paul is…’ I’m like, ‘That’s so weird that you’re watching the screen when you say that,’” he enthuses.

Kynaston has found, since filming earlier this year, that he’s been enacting the matter-of-fact approach of his character when faced with the junctures life presents. “What I did find with Hungry Paul that I’ve been trying to exercise is the willpower of not overthinking things. This whole mantra and philosophy: ‘Try not to sweat the small stuff.’ There’s a line in the show where my dad is talking to my sister, and he’s saying, ‘I’ve been wondering, maybe I should have been there for you more as kids.’ Hungry Paul says to him, ‘Too late, it’s all gone.’ And there’s something kind of gorgeous about that. Just live in the present, right?”

One thing that didn’t rub off was Hungry Paul’s inclination for staying at home. “I’m very rarely in of an evening,” Kynaston admits, enjoying the rich social life a Hackney existence has long offered its often creative community. “I’m out and about. I love being out and going to the pub and being with my mates or going for a dance.” Last year, more than 200 people attended his 30th birthday party at local venue Night Tales, including his parents, siblings and the several drag performers within his circle. “I think my mum’s question [to them] was, ‘What do you keep in your handbag?’” he laughs.

“I play much more introverted characters than I am in real life,” he continues, although he’s unsure why. “Maybe you’re able to access it and then throw it away? Or if you’re an introvert playing an introvert, then maybe it would get a bit intense. I mean, I don’t think I’m like, life and soul and massive extrovert. But I really enjoy the company of others.” It doesn’t mean he doesn’t crave the stillness of his countryside roots when the moment requires it, however. When the opportunities of both Leonard & Hungry Paul and Lady came calling, he was back home in Wales after having a “classic actor freak out of, ‘I’m never going to work again’” during a quiet spell. He retreated to the family farm, “Just to get some fresh air and be like, ‘Oh, maybe I’ll move back and be a farmer, and that will all be fine.’” He filmed self-tapes for both projects in his dad’s study. Kynaston is something of a professional at the modern-day pre-recorded video format for most acting auditions, however. He’s been the proud co-owner of Hackney Self Tape Collective, alongside fellow actor Thomas Flynn (Red, White & Royal Blue, Bridgerton), since February, aimed at providing a space for the process to be completed with ease.

Self-tapes submitted, Lady was secured first. And so, when it came to the chemistry read with Lawther for Leonard & Hungry Paul – unusually conducted on Zoom – Kynaston was on set, and had to grab 10 minutes between takes. The conditions were less than ideal – “We were doing this stupid scene where I had to have my face smashed on the floor, covered in egg and blood. It was really stressful,” he laughs. Thankfully, his existing friendship with Lawther helped seal the deal.

Such chaos does offer a keyhole glimpse into Lady, which was pitched to Kynaston as following a “‘Fabulous, mad woman in a big manor house as she invites a camera crew to come and film her every move because she thinks she’s so very interesting.‘” As Kynaston explains, “It turns out she is very interesting, but not for the reason that she thinks.” The judge of children’s talent contest, Stately Stars, Clifford’s Lady Isabella throws a curveball when she declares she would, this year, like to compete against the children. As Isabella’s conduct proves more absent-minded and erratic by the minute, Kynaston’s fictional Abrahams – a determined if green documentarian – cashes in on the haywire situation he’s been granted access to. “He’s a bit of a user,” Kynaston admits, “but it’s because he hasn’t had much luck, and you see later on in the film he has something that is holding him back that he’s not in control of.”

“Also, Isabella is hard work,” he adds. “But she also is a product of her culture and also needs protecting and needs some love. She lives on her own in this big, massive fucking castle and needs somebody there to just come and make a cup of tea. Her version of making a friend is paying a whole crew to come and film her because she’s so interesting.”

Playing a fictional iteration of one’s director could prove surreal. “I guess the character is maybe an extension of [Sam],” Kynaston explains. “I think he just wanted to keep that realism. Although Sam the character is a lot more of an asshole than Sam in real life. But maybe [real-life Sam] was able to exercise some demons in there, and put his foibles out there on screen.”

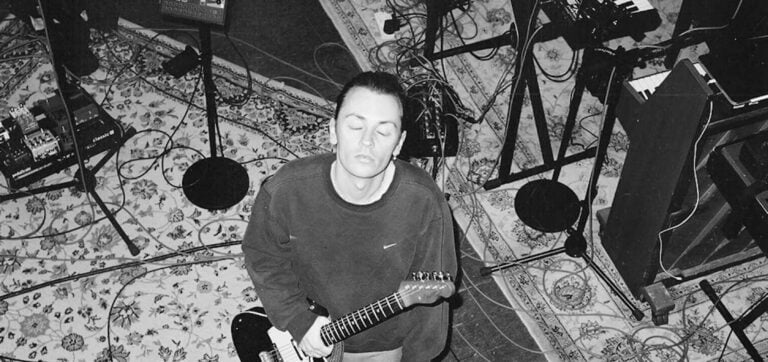

The mockumentary style meant the feature shot on one camera, with no lighting, and so filming days would be dense, with the usual breaks to rejig set-ups off the schedule. “We were basically shooting all day. It was absolutely knackering. And Sam would just let the tapes run and run, and sometimes it would be like, ‘We just now need you guys walking through the house, dicking around,’ or playing ping pong. And some of those takes would be half an hour. But we also just threw ourselves into it.”

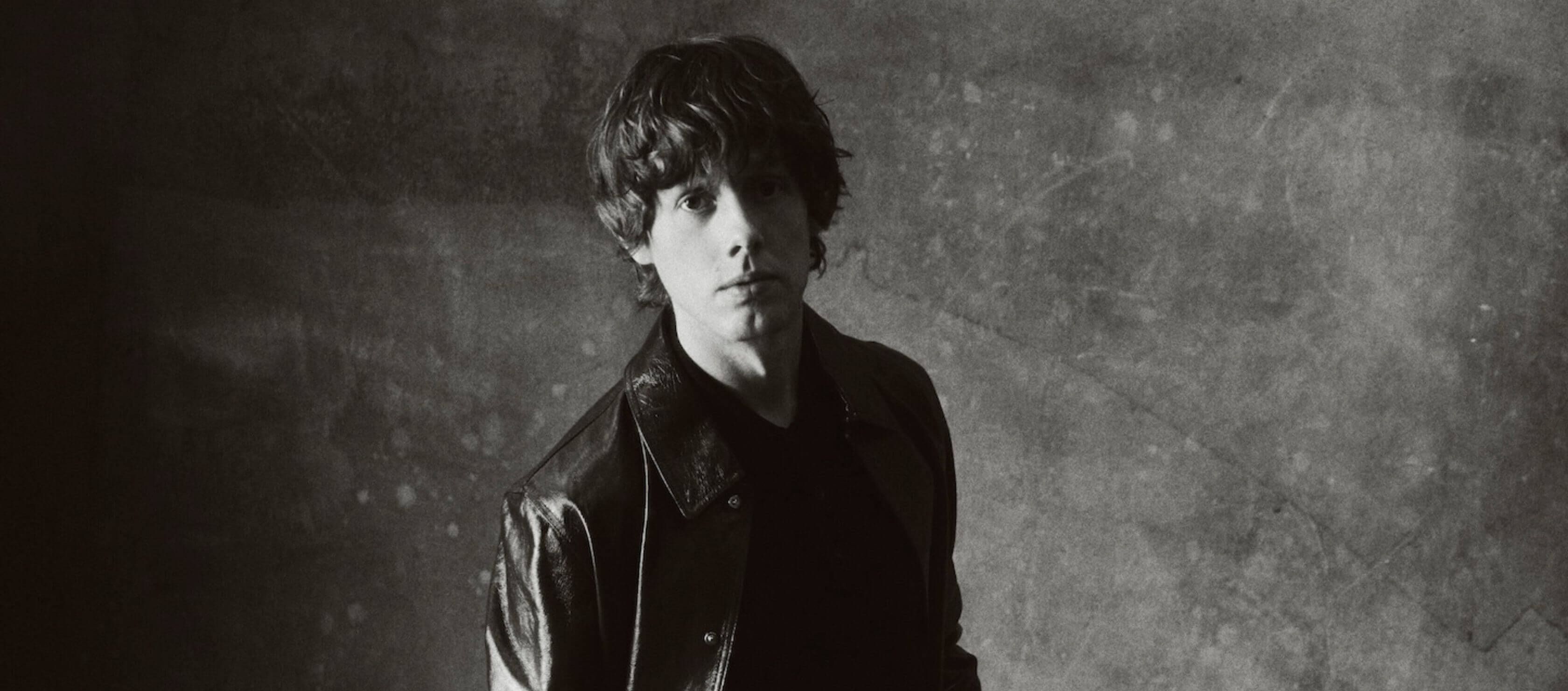

The lack of the usual stop-start process of screen acting was perhaps helpful preparation for Kynaston’s upcoming return to the stage in Man and Boy. The stage is a comfort zone for Kynaston, however. It’s where he can perform at his most passionate. “You feel more of an ownership over your work. As a company, you create that show from the ground up, from literally nothing to the whole of the British press sitting in the room.” And Kynaston reads all of the reviews that follow – not just of his own performances, but any new major theatre launch. Hours before we meet, The Guardian’s rarely-used zero-star rating is deployed for Ryan Murphy’s Kim Kardashian-starring legal drama All’s Fair. “Do you think [The Guardian] is trying to make a statement there?” Kynaston weighs in. “One star is bad, but surely there’s something salvageable in it… like, ‘The makeup is good.’”

Man and Boy is his first time acting before an audience since Long Day’s Journey Into Night. “I love [doing theatre]. I really love it,” he enthuses. The play also signals his first appearance at the Southbank’s iconic National Theatre, a “full-circle moment” given his debut stage production, 13 years ago, was another Terence Rattigan piece. It’s the kind of career pinch-me moment befitting of Kynaston’s current epoch – and the fourth decade of life he’s currently easing into. His milestone birthday has been accompanied by a change in his casting bracket. “I was very much playing teenagers for a long time and then, people in their early 20s, and now, Hungry Paul is in his 30s,” he smiles. As for the pace of his career, so far? He’s happy with it, interpreting his success with a Hungry Paul-esque pragmatism. “Hopefully the [career] choices that I’ve been making are quite solid.”

Photography

Victoria Stevens

![Picture of “When We Were Developing Series [2], We Were Very Conscious Of The Live Debate About What It Means To Be British”: Tom Hiddleston On The Night Manager’s 2020s Comeback](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2Fdigsfo.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_AhPDpVcvBHi6ZdoK89nsTL2Qj1WA)

![Picture of “[The Bridgerton Press Tour] Is Like Being On Some Sort Of Hallucinogenic Drug”: Luke Thompson Is Next In Line](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F01%2FLUKE-THOMPSON-hero.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_AhPDpVcvBHi6ZdoK89nsTL2Qj1WA)