From The Queen to Jimi Hendrix – David Montgomery’s eye has made him one of the defining fathers of modern photography. For Man About Town lensman Max Montgomery, he’s also dad. The pair sit down to talk craft and capturing legends.

“I always say I’m a bit like a doctor,” David Montgomery says. “Somebody comes to me and they’re not well, and I try to make them better. Whoever it is – a dustman or The Queen, I will try my best.” With a subject list as expansive and illustrious as photography icon Montgomery’s, deploying the indiscriminate professionalism of those bearing stethoscopes has served him well. “But naturally, the Queen was a one-off,” he admits. “She was like a god for the rest of the world. Nobody could get near her, and here I was in the room with her.”

Brooklyn-hailing Montgomery became the first American to capture Queen Elizabeth II, travelling from his adopted home of London, in 1967, to depict the late monarch in the more domestic surrounds of the Balmoral estate. Subsequently, he’s said to have never felt trepidation prior to a shoot. His later subjects would have tested the nervous system of most, however. There were the 20th-century cultural dignitaries – Andy Warhol, Jimi Hendrix, Barbara Streisand, Mick Jagger, Dolly Parton – to name only a fraction. And five British prime ministers, including Margaret Thatcher twice, plus Bill Clinton. Muhammad Ali just “growled at me like a bear,” he tells his son Max Montgomery, over Zoom, on one of the final searing days of London’s summer. “I kept saying to myself, ‘He can’t hit you. It’s against the law.’”

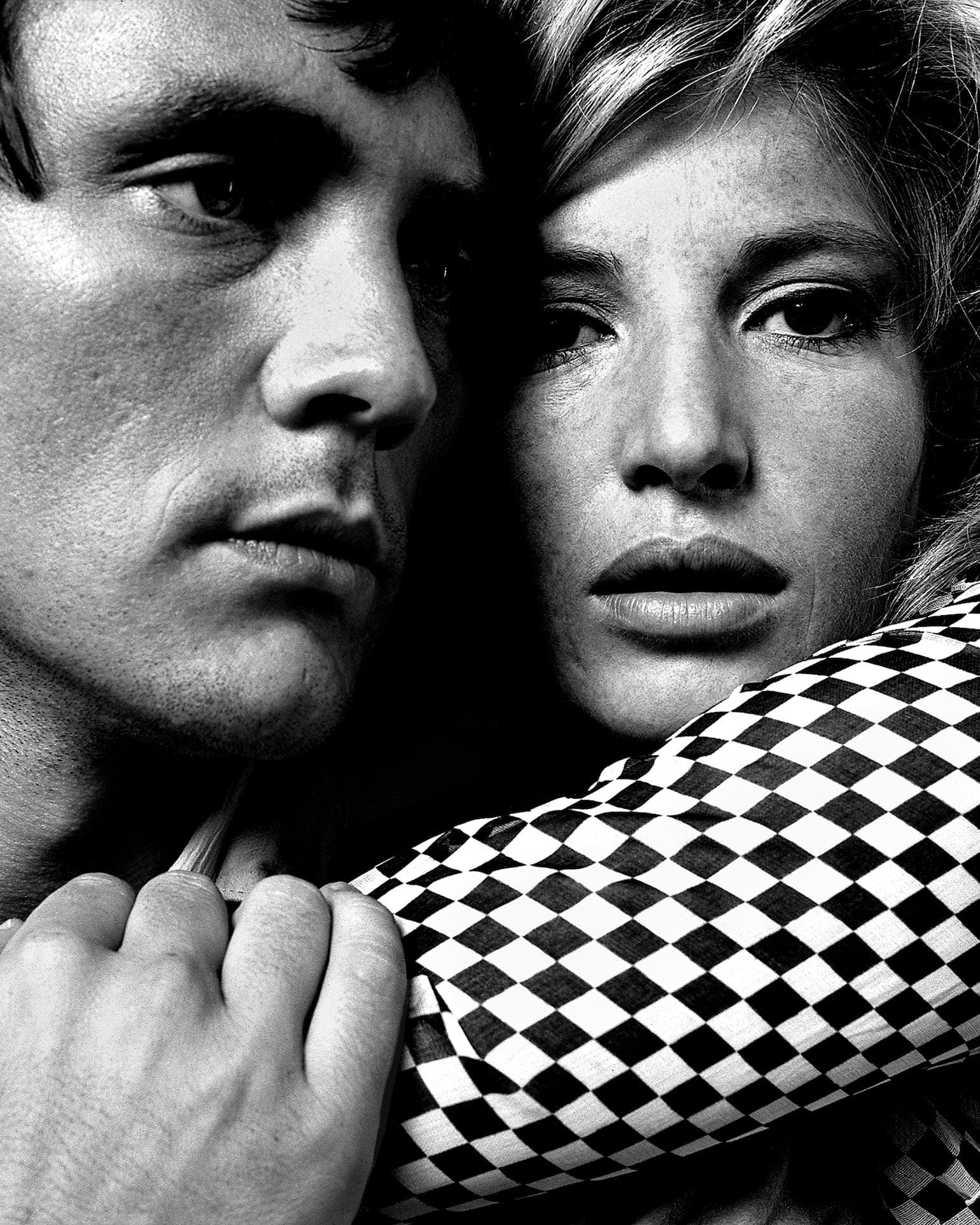

Terence Stamp and Monica Vitti, 1966

Max and David connect at tail-ends of their respective days – for Max, it’s morning in LA, the city in which he’s carving out his own career as one of the most notable Hollywood photographers of today. David, now aged 88, is in the studio-turned-home in Chelsea that he first rented in 1960 for £4 a week upon his arrival in London. Father and son were together, in person, some weeks earlier, when Max was tasked by Man About Town to lens Matthew McConaughey for the actor’s Autumn/Winter cover. The shoot took place back on UK soil, allowing David to accompany Max to set. “[That shoot] was everything it should have been,” Montgomery senior enthuses of his one-day return to the office.

These days, David has largely put down his camera. “So I’m very happy that you are carrying the light onwards,” he tells Max. For now, however, Max is taking a retrospective glance at his father’s story, turning the lens on a decades-spanning legacy forever etched into their craft’s annals. “I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about my past,” David says as they begin their conversation. “Tell me what you were dreaming about,” Max replies.

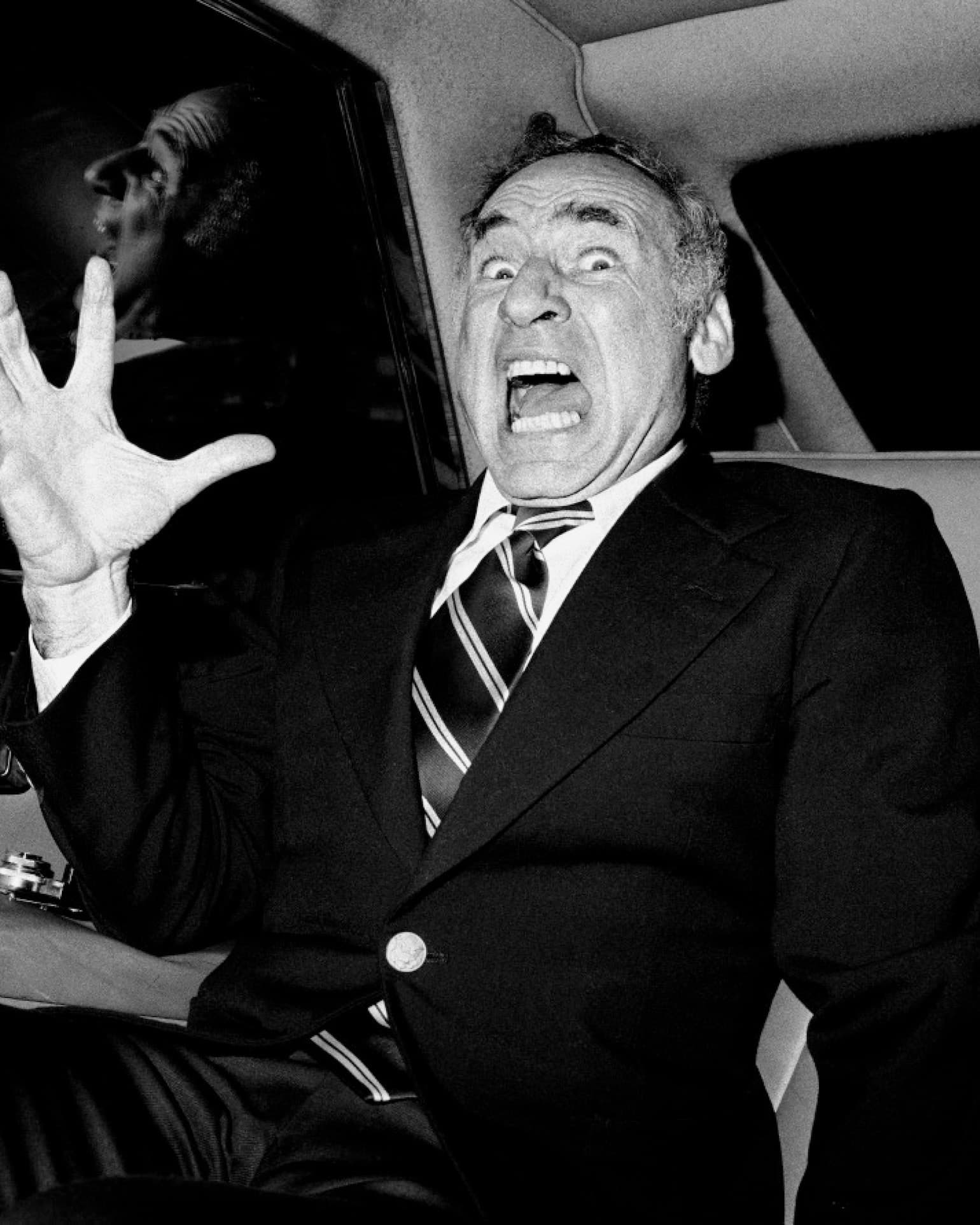

Mel Brooks, 1980

Max Montgomery: I want to go back to the beginning. Do you remember the first photo you ever took that was of significance to you?

David Montgomery: I took a picture of a jazz musician called Ben Webster in Birdland in New York. It was all dark except for a spotlight on him. His skin was bleached white, and the front of the saxophone was out of focus, and I just thought, ‘Hey, this is magic.’

MM: You’ve had this whole journey with photography. It’s something that I know you think about a lot. Something that you love, something that you at times have loved less.

DM: When I started, I never really wanted to be a certain kind of photographer. I just wanted to take pictures, nothing more than that.

MM: When you look back at your archive, are you more excited by the photos you took of a Jimi Hendrix or an Alfred Hitchcock than the photos of girls in clothes for Vogue?

DM: Yeah. But then there are people who feel that any picture that was in Vogue belongs in a museum. I think it’s just selling a dress.

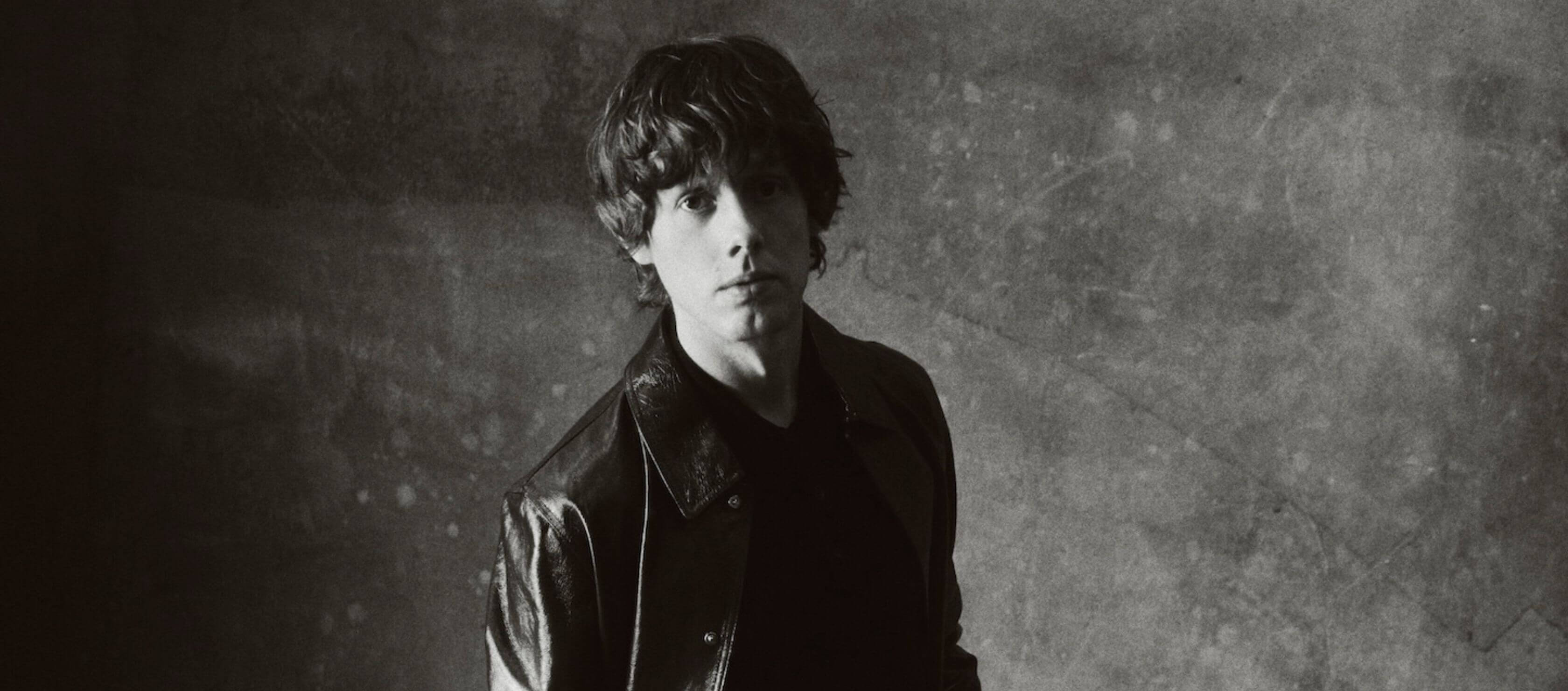

Alfred Hitchcock, 1976

MM: Who is the most difficult person you’ve ever photographed or been on set with?

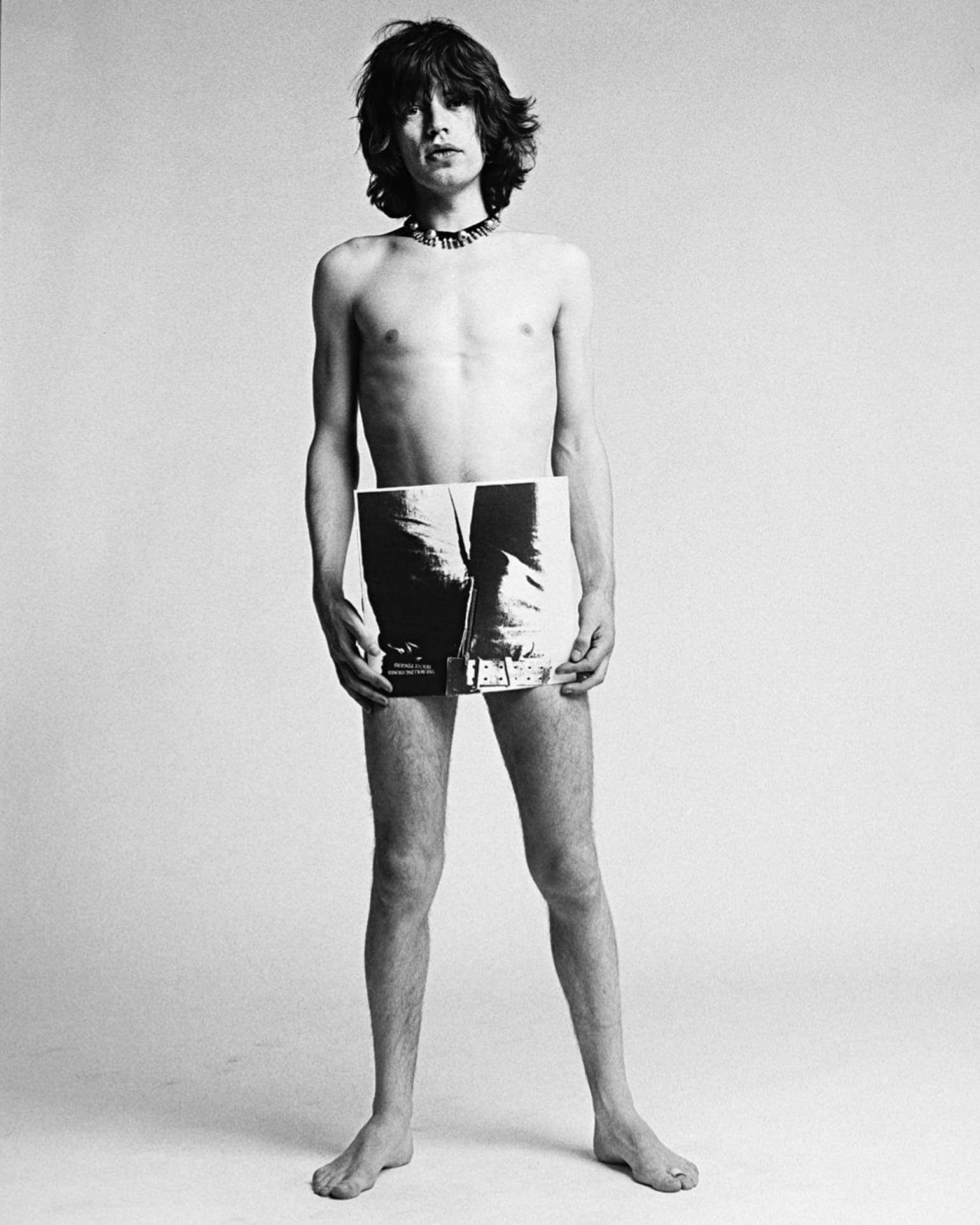

DM: Well, there are a couple. Prime Minister Ted Heath – tricky. Barbara Streisand – tricky. Mick [Jagger] was a bit cantankerous, but I wouldn’t put him on top of my hate list. Muhammad Ali – he was nasty.

MM: Sometimes when I’m photographing people and they’re really bad, I think, ‘Are they an asshole or did I catch them on a bad day?’ I try to put myself in their shoes.

DM: Why would anybody in their right mind have their picture taken and then be nasty to the photographer? That’s like going to the dentist and saying, ‘Give me your worst shot,’ because then maybe deep down, the photographer who has to look like none of this is affecting him thinks, ‘Well, screw you, babe. I’m not going to give you the best I’ve got. You’re going to get the worst.’

MM: When I get given a really big assignment, I think to myself, ‘I want to make sure that these photographs, in some sense, stand the test of time.’ When I look at your photos of, for example, The Queen, I just wonder if you can put yourself back into your mind at that time when you were asked to go to Balmoral. What was your process like? Were you aware of what those images would mean to you in your life?

DM: The story goes like this… The Observer called me up to take a picture. I was young, I had been working maybe two years, it was 1964. They asked me if I would like to take a picture of The Queen because they liked whatever pictures I was taking at the time. And I thought about it for a minute, and I said, ‘No, thank you. I don’t think I can do it.’

And then I got home and told my wife about it, and she said, ‘When are you going to shoot it?’ And I said, ‘I’m not going to shoot it.’ And she said, ‘Well, I think you’re being very stupid.’ And I remember exactly, it was 5:30 pm on a Friday afternoon. I called up The Observer and I said, ‘Hey, if you haven’t got another photographer, I’d like to do it.’ And then I was just thinking about all the pictures of her and how I would do it, blah blah blah. When I got there, she was very nice. There was no hair and makeup, and her skin was like a pearl. And the weather was okay. We were in a room the size of an aeroplane hangar, and I explained to her that the light meter said the exposure was half a second. I said, ‘So that means you have to hold very, very still.’ And she said, ‘Not a problem.’

MM: Did she seem like a regular person to you?

DM: She was extremely nice. I didn’t ask anything outrageous, but whatever I asked her to do, she did it no question. At the end of the shooting, we all wanted to hug her and kiss her. She was like an aunt or a grandmother. But of course, you didn’t do that. And I’d gone through life with ups and downs and hardships, I’d come to a foreign country, and then I’m photographing The Queen of England.

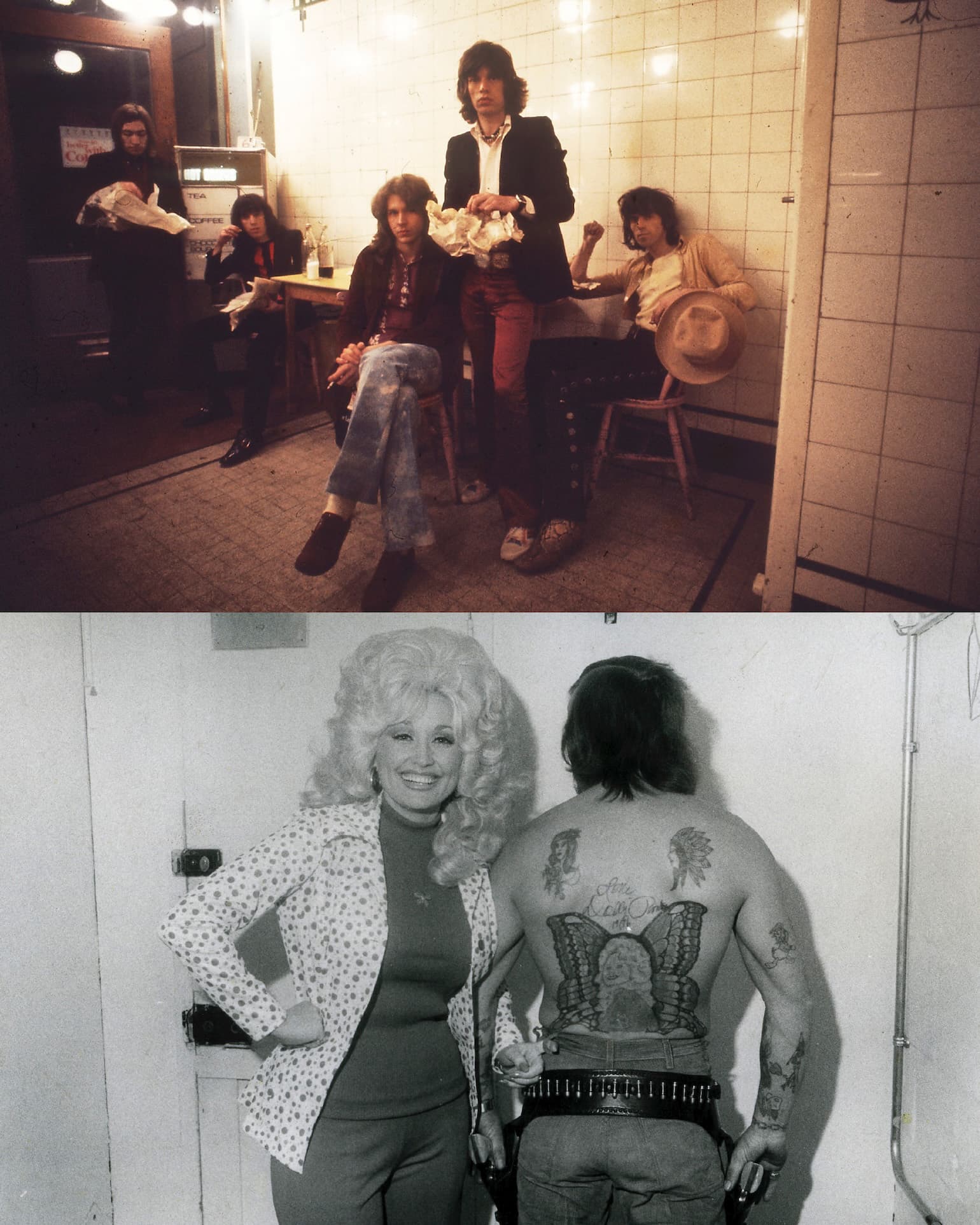

MM: What about when you were photographing Dolly Parton? I know that you were big into country music, and she was obviously a smoking hot babe. How did you end up photographing her in a lawyer’s office, and did you ever fall in love with the people you photographed, even just for 45 minutes?

DM: I don’t know how we ended up in that guy’s office, because it was in St Louis or some place, and there was nowhere to shoot her, so somebody said, ‘Oh, my friend’s a lawyer, we can use his office.’ Dolly thought it was pretty hysterical.

I always liked models. Most models, the really good models, can transform themselves into this super-vision of body movement and looks. They are superlative, better than your best dream. It’s like moulding clay. It doesn’t really exist. And some people don’t learn that, and they fall in love every 45 minutes, or they fall in love with the image which doesn’t exist.

MM: I think when I look back at some of your Vogue magazine shoots, the fashion photographs, especially the ones where you put [models] in East London and surrounded them with people, they were incorporating more storytelling. Did you ever see yourself as a director as much as a photographer?

DM: Well, I think it goes a little deeper than that. With a lot of those photographs, there was absolutely no budget. There wasn’t enough money for a ham sandwich for everybody. And so if I were shooting for Vogue, say, two or three times a week, and then a bit for Harper’s Bazaar, you’re like a comedian. You’ve got to keep coming up with new jokes.

MM: Who is the most difficult person you’ve ever photographed or been on set with?

DM: Well, there are a couple. Prime Minister Ted Heath – tricky. Barbara Streisand – tricky. Mick [Jagger] was a bit cantankerous, but I wouldn’t put him on top of my hate list. Muhammad Ali – he was nasty.

MM: Sometimes when I’m photographing people and they’re really bad, I think, ‘Are they an asshole or did I catch them on a bad day?’ I try to put myself in their shoes.

DM: Why would anybody in their right mind have their picture taken and then be nasty to the photographer? That’s like going to the dentist and saying, ‘Give me your worst shot,’ because then maybe deep down, the photographer who has to look like none of this is affecting him thinks, ‘Well, screw you, babe. I’m not going to give you the best I’ve got. You’re going to get the worst.’

MM: When I get given a really big assignment, I think to myself, ‘I want to make sure that these photographs, in some sense, stand the test of time.’ When I look at your photos of, for example, The Queen, I just wonder if you can put yourself back into your mind at that time when you were asked to go to Balmoral. What was your process like? Were you aware of what those images would mean to you in your life?

DM: The story goes like this… The Observer called me up to take a picture. I was young, I had been working maybe two years, it was 1964. They asked me if I would like to take a picture of The Queen because they liked whatever pictures I was taking at the time. And I thought about it for a minute, and I said, ‘No, thank you. I don’t think I can do it.’

And then I got home and told my wife about it, and she said, ‘When are you going to shoot it?’ And I said, ‘I’m not going to shoot it.’ And she said, ‘Well, I think you’re being very stupid.’ And I remember exactly, it was 5:30 pm on a Friday afternoon. I called up The Observer and I said, ‘Hey, if you haven’t got another photographer, I’d like to do it.’ And then I was just thinking about all the pictures of her and how I would do it, blah blah blah. When I got there, she was very nice. There was no hair and makeup, and her skin was like a pearl. And the weather was okay. We were in a room the size of an aeroplane hangar, and I explained to her that the light meter said the exposure was half a second. I said, ‘So that means you have to hold very, very still.’ And she said, ‘Not a problem.’

MM: Did she seem like a regular person to you?

DM: She was extremely nice. I didn’t ask anything outrageous, but whatever I asked her to do, she did it no question. At the end of the shooting, we all wanted to hug her and kiss her. She was like an aunt or a grandmother. But of course, you didn’t do that. And I’d gone through life with ups and downs and hardships, I’d come to a foreign country, and then I’m photographing The Queen of England.

MM: What about when you were photographing Dolly Parton? I know that you were big into country music, and she was obviously a smoking hot babe. How did you end up photographing her in a lawyer’s office, and did you ever fall in love with the people you photographed, even just for 45 minutes?

DM: I don’t know how we ended up in that guy’s office, because it was in St Louis or some place, and there was nowhere to shoot her, so somebody said, ‘Oh, my friend’s a lawyer, we can use his office.’ Dolly thought it was pretty hysterical.

I always liked models. Most models, the really good models, can transform themselves into this super-vision of body movement and looks. They are superlative, better than your best dream. It’s like moulding clay. It doesn’t really exist. And some people don’t learn that, and they fall in love every 45 minutes, or they fall in love with the image which doesn’t exist.

MM: I think when I look back at some of your Vogue magazine shoots, the fashion photographs, especially the ones where you put [models] in East London and surrounded them with people, they were incorporating more storytelling. Did you ever see yourself as a director as much as a photographer?

DM: Well, I think it goes a little deeper than that. With a lot of those photographs, there was absolutely no budget. There wasn’t enough money for a ham sandwich for everybody. And so if I were shooting for Vogue, say, two or three times a week, and then a bit for Harper’s Bazaar, you’re like a comedian. You’ve got to keep coming up with new jokes.

What are you going to do to make it look a little different? Just a little something. ‘Let’s go out by the river.’ ‘Let’s go to this place, that place.’ And then try and make it so just you and your little camera – the magic box – gives it another look.

Queen Elizabeth II, 1967

MM: Talk to me about Jimi Hendrix.

DM: Okay, well, that was pretty simple. I mean, nobody had ever heard of him – this American guitar player. The story goes like this… apparently, Linda McCartney shot the [Electric Ladyland cover] first. She took a picture of two little kids, a white boy and a Black boy, playing in the park. They looked at this picture and they said, ‘What the hell is this about? So they said, we need a good picture of [Jimi].

MM: So your shoot was a reshoot?

DM: Oh, that was a reshoot.

MM: I didn’t know that.

DM: I worked a lot with a guy called David King. He was the top art director at The Sunday Times Magazine. And David used me to shoot a few album covers. So he says, ‘Look, we got this guy, Hendrix. We’ve got to do something shattering.’ And because I had done a lot of group shots, he says, ‘We want to have a bunch of girls.’ So I said, ‘Okay.’ And they rounded up all these girls from nightclubs. I had nothing to do with that. I was just waiting in the studio. And all these weird-looking girls came in. They were strange. And they take their tops off, and I take a Polaroid, and the art director says, ‘This is no good. They’ve got to be naked.’ So I’m thinking, ‘Well, how are you going to take a picture of naked girls that’s going to be able to sell all over the world?’ Well, anyway, I took the picture. When I look at it, it’s pretty weird. I would have done it much better five years later.

Mick Jagger, 1971

MM: I wonder where these women are now and how many of them are still alive.

DM: Some people have tried to track them down. But then I took that other picture of Jimi on his own in front of the fire with the flames behind him, and that was one where I had more control over the art direction.

MM: You were close to incinerating him at one point, no? I think about how you would do that now if Jimi were alive. You’d have to have a fire marshal. You would have a whole production team.

DM: It’s a miracle we didn’t cook him alive, really. He was only six feet in front of this 20-foot-high wall of flame.

MM: How did you make the flames?

DM: Jimi was standing there. I had two assistants behind him, and then some background was up. One assistant had a cigarette lighter, the other assistant had an oil can with petrol in it. We shot it in The Roundhouse, which was where they repaired locomotives. So it was a concrete floor. He poured the petrol on the floor. And I said,

‘Okay, Jimi, get ready.’ I said, ‘Light it.’ And the guy lit it with a Zippo, and it sounded like a jet plane taking off. And there was a wall of flame, 20-foot high. I just started shooting. But the flames didn’t stay up that long, so then it started falling down around his back.

MM: You just did one take?

DM: Yeah. That was the thing back then, it was a bit loose and magic, and nobody knew what was going to happen.

Sophia Loren, 1966

MM: This is a bit off topic, but you know everybody now has a phone, everybody’s on social media, and if you go into a nightclub, everybody’s photographing you. It seems like the celebrities had a little more privacy back then, and everything was a little bit more intimate and magical. You moved to London in the swinging 60s.

DM: Yeah. But if you ask, ‘What would be the difference between whatever pictures I took and whatever pictures Annie Leibovitz did for Vanity Fair?’ The main difference, I think, is that the British people, the wildest people I could think of, were still quite reserved. And also, the budgets were so low. You’re lucky if Michael Caine or even David Bowie or Paul McCartney would actually show up. But if they showed up, they were like normal people, like ‘Let’s do it and get it over with.’ It didn’t have the theatricality of the American magazines, because there was no money.

MM: Who’s the one that got away? Or who is still alive that you would love to photograph?

DM: Elvis. I’ll tell you, Mae West. She was a blast. She was quite a number. She was great. Nobody knew anything about her.

MM: You were a jazz drummer. You’ve taken these iconic images of so many musicians – The Who, Sade, The Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney. You made quite a contribution to music imagery. And you are still playing music. You’re part of an Irish band?

DM: It’s sort of an Irish-tinted, rock band, yeah.

MM: And you’re down with all the boys playing a couple of times a week in Camden, drinking Guinness and having a good time.

DM: Yeah, as a drummer. I don’t practice at all. And they play very fast. It’s my job to keep everybody together and keep the tempo constant. I just try to keep very simple time, not get in anybody’s way and just set this locomotive going along.

MM: Are you still taking pictures? And what does that look like for you?

DM: Well, to tell you the truth, I feel that, if I see something, I don’t have to take a picture of it to prove I saw it. I’ve got thousands of photographs. I wonder what the hell I could possibly see on the streets of London that nobody else hasn’t seen a hundred times. And then all of a sudden, some quirky thing happens. If you look at Gary Winograd’s pictures of New York, the most mundane, stupid, idiotic, everyday things he made into the unknown.

MM: Which of those guys, like Winograd, Louis Faurer, Robert Frank, were your heroes?

DM: Well, I’ll tell you something, Tony Ray-Jones. Nobody heard of Tony Ray-Jones. And poor old Tony Ray-Jones. Nobody used him, and he died in obscurity. I think Martin Parr ripped him off. In my opinion, ninety-nine per cent of all the Tony Ray-Jones psyche is Martin Parr.

(Top) The Rolling Stones, 1971 (Bottom) Dolly Parton, 1970s

MM: I think so many photographers are influenced by so many photographers. I personally am reluctant to say ‘total rip-off’, but I would say heavily influenced. Martin Parr’s photos are so colourful, and I think Tony [mainly] shot in black and white. The colour was a large part. They are stylistically similar, but maybe the narrative was a little different. You were on set for my shoot with Matthew McConaughey. What were your reflections? He walked in the door, and the first thing he did was come over and give you a big hug.

DM: I thought he was everything a movie star should be, but hardly ever is. So he impressed me. And then when I said I was your dad, he was extra nice. It was just really nice to have been in that surrounding, for me, because I was just an observer. There was a synergy between you and him.

MM: I found it very useful having you there because you had lots of great ideas for poses and how to manipulate the setup, often to give it a bit of a sense of humour, which I think is an incredible skill. A lot of my favourite photographers, sometimes I look at their photos and I think, ‘Just even the way they left one cup of tea in one place it shouldn’t be or one newspaper.’ Things that are a little bit off. When I look at your images, something that I quite consistently see is something like the lampshade is not straight. And I wonder, is that a muscle that you’ve trained or is that something that you’ve always had?

DM: Both. Things can be too perfect. You don’t want that. A little bit imperfect is more perfect than perfect. Plus, none of us are perfect.

MM: Who are your top three photographers?

DM: There are the top three after David LaChapelle. We’ve got to put him in a special box, because I think he’s quite an amazing character. He’s Superman. But I love Avedon for the most part. And I like Louis Faurer.

MM: Irving Penn?

DM: Well, he’s great. He’s like Michelangelo, that guy. There’s a guy called Danny Lyon. You know him? He shoots like Robert Frank.

MM: Obviously, I am following down the path that you have chosen to make a living. I have two boys who are your grandchildren now, and I almost wouldn’t want them to be photographers, because it’s such a strange and uncertain existence, as great as it is. I would love them to be successful photographers, but it is just such a complicated path to take. What have you tried to instil in me to help me progress?

DM: You know, Max, it’s interesting because my father, bless his soul, loved photography. He loved to hold the camera, and he didn’t think like we think in the artistic way. He just liked to take a picture. And so whatever that love is that he had, it must have gone on to me and on to you. We’ve got no control over it, that’s how it is.

MM: I like that it’s a love passed on.

DM: And the fact that you have left this wet country and gone somewhere else, I always tell everybody, your photographs are ‘An Englishman abroad.’ You can see the most obscure and different things in California or anywhere in America that most American guys miss. Because it’s so commonplace for them that they would never think, ‘Hey, this is special.’ You’re out there doing it.

MM: I think we should try to do a shoot together soon. Maybe we can do it for Man About Town? It’d be fun.

![Picture of “This Mixtape Is Kicking The Door Open To The [Tsatsamis] Project”: Tsatsamis Talks Tsycophant](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2FTsatsamis-Hero-export-768x335.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_HaJn5DvkMiR7b3yLhqRbLkCcwnHD)