With another year of celebrity overexposure hitting a peak, Alex Russell’s directorial debut Lurker, starring Archie Madekwe and Théodore Pellerin, arrives as an eerily modern commentary on internet self-mythology.

A spiritual companion watch to Stan Twitter-satire Swarm, or even Eminem’s horrorcore hit from the year 2000, of which the term originated, Alex Russell’s Lurker is the unexpected parasocial parable closing out another year of cultural commotion and celebrity cringe.

Rachel Sennott’s I Love LA is a comedic love letter to the city that put her on the map, continuing to dominate Hollywood headlines while it still airs on smart devices. To her benefit, or detriment, it’s a chaotic look at internet creatives and WeHo’s gay scene, how to come of age with a vocal fry and a very online sensibility in vapid social surroundings. It’s certainly nothing new, rather taking an overfamiliar concept and running with it for the zillenial generation.

But in Lurker, through the ugly guise of a modern psychological thriller, Russell not only captures the current climate of entertainment’s elite. He chews up and spits out all the aforementioned showbiz ingredients that make up LA’s recipe for success. Nominated for four Film Independent Spirit Awards, it’s the perfect follow-up to an already standout career in TV: credentials include The Bear and an Emmy-winning run as co-executive producer for Beef.

“I think it just comes from my experience in LA, a lot of it we shot there,” Russell tells me through a fit of pre-lunch giggles. “The process was me being shown a lot of options at every stage, whether it was locations or the specific style of music.” Our conversation takes place at London’s Soho Hotel, Lurker is set to premiere that evening at the Prince Charles Cinema for the 2025 BFI London Film Festival. Sitting beside Russell are the rising stars of his film, Saltburn’s Archie Madekwe and Solo’s Théodore Pellerin, the latter of the two in quiet hysterics with the writer-director. Is there something on my face?

His multi-striped jumper washing out the sea of black that surrounds our junket setup, Madekwe, apologetic, reassures me that this is a combination of hunger and jet lag. The high of being made to film “a weird social thing” for the journalist before me. It seems pretty on the nose, given the nature of the project they’re promoting. Out of the threesome, Madekwe is the most composed, quite unlike his perfectly entitled pop star character, Oliver.

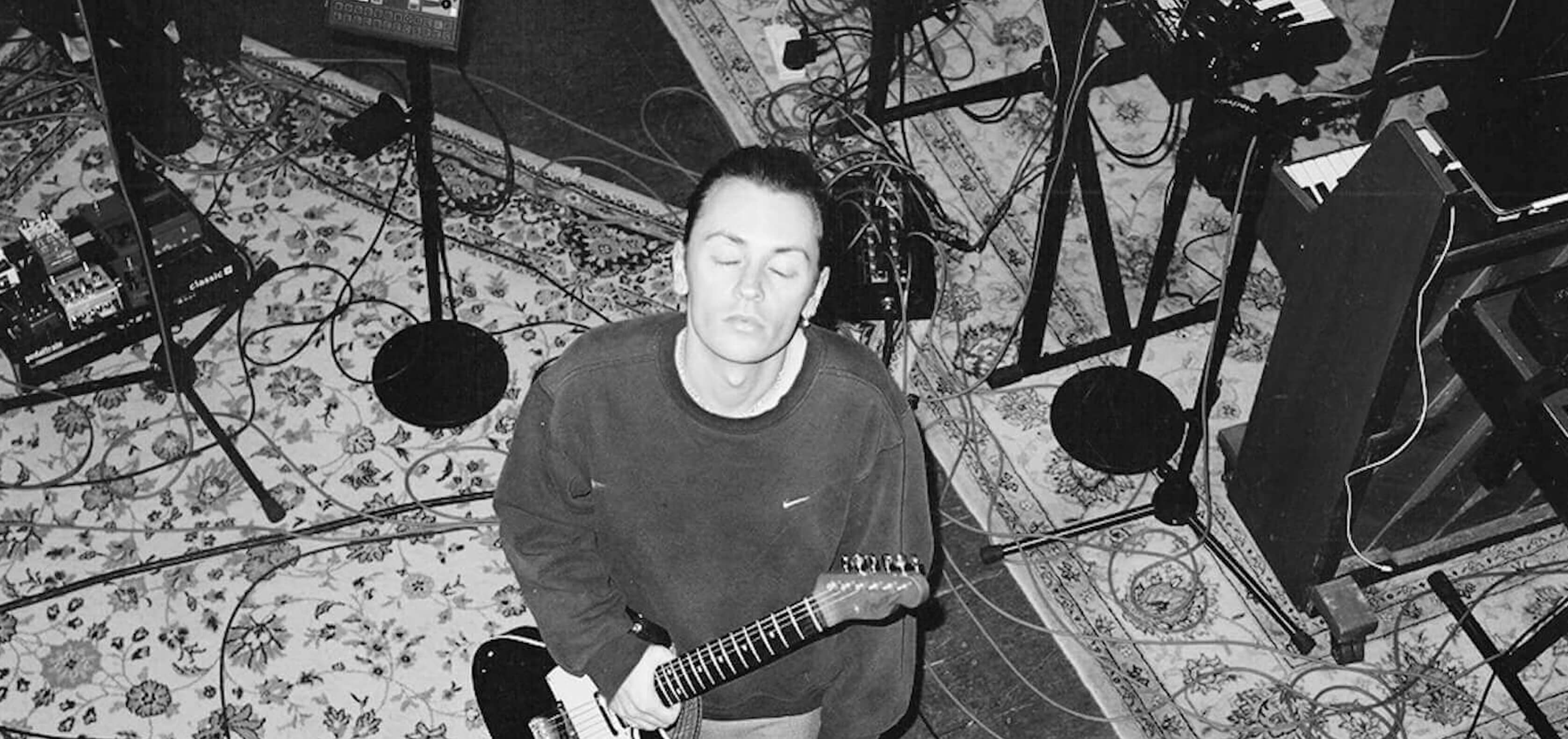

Through music video montages and painfully real moments of mollycoddling, Oliver makes for easy prey as the object of online fixation for Pellerin’s Matthew, where fan fiction meets frightening reality in a rousing performance as a twenty-something retail clerk who will stop at nothing to worm his way into the in-crowd. Friendships are tested; uber-tense interplays are scored by brilliant original music from Madekwe. “It seems like a lot of people are very triggered by it,” he says of the film.

In conversation with Man About Town, the threesome talk LA realism, masquerading male dynamics, and playing out the pitfalls of proximity to fame on the big screen.

Lurker is written from the point of view of a follower rather than the star. What made that desperate desire for proximity more compelling to explore than the typical “celebrity under siege” narrative?

Alex Russell: It’s a great question. I mean, I think when I was first considering, or when I was first sort of circling this world as setting, I probably thought of versions of it where Oliver or that character was sort of the main perspective. But I don’t think I was able to key into it that easily. It just felt fake for me to write it from Oliver’s perspective. I think I could relate more to an outsider. Then, obviously, the subjectivity starts to change a little bit, and these characters are a little more similar than you first imagine. But I think it was just when it started to spill out of me, when I thought of it from Matthew’s perspective.

The film observes male competition and quiet jealousy in a way that mirrors real, silent hierarchies among men, not just in Hollywood.

Archie Madekwe: A friend of mine, Aidan Zamiri, was like ‘Oh my God, I’m never calling myself a visual artist ever again.’ This really is a tale as old as this time; it happens again and again. There are so many visual artists, people, who become successful alongside somebody else who is more successful. Not saying this for Aidan, he’s an artist in his own right. But riding the coattails of somebody else, that happens so often, and I think that it’s a lot of people’s biggest fear, of ‘where does my success stem from? Am I doing something that feels authentic?’

A lot of people don’t speak about it because it’s so new, that thing of how accessible and easy fame, or proximity to fame, is now, and the luxuries that that brought so many people. All of a sudden they’re seeing it played out on the big screen. I think it was a hard watch and a hard pill to swallow for a lot of people. I’ve found that interesting in some Letterboxd reviews.

The entertainment industry, of course, champions men with power and access like Oliver, the envy that shrouds his circle is hard to ignore. From working in entertainment, did you recognise and channel dynamics from real life scenarios?

Théodore Pellerin: I didn’t, I don’t know, it’s a very different world than where I’m from, or what I know. Music is also so different from cinema, especially independent French-Canadian cinema. There’s always parts of ourselves that we draw from, but to me, it was connecting to being a kid trying to fit in, trying to make friends, than really the actual world of fame and music and cinema.

What attracted you to the character of Matthew in the first place?

TP: It’s a great script. It was, really, as simple as that. Matthew, I mean, I love despicable characters. I think they’re so fun, and I love to hate them, and at the same time, love playing them. I love to get to be the worst versions of myself sometimes on screen.

Stepping into such a volatile role, did you ever have any concerns about how it would be received, particularly by young male audiences?

TP: No, I never think of audiences, because I don’t think I’ve ever made a movie that was seen by anyone.

AM: So untrue.

AR: You say young audiences, what’s that demo? I feel like I knew younger audiences would get it, but I think I was just exploring what I wanted to say, and I hoped that all kinds of people would gravitate toward it. I was more curious about what my grandma would think.

AM: My whole family is coming tonight, for the first time.

AR: Oh, my God. What’s their demo?

AM: 60 and above.

What stylistic references informed your satirical interpretation of LA, Alex?

AR: A lot of the choices were just a little more specific, because I’d spent the time there. I remember a first thought of the house being in the hills, made out of a glass mansion or whatever. It felt more realistic to have this rented, pre-furnished place that was not huge like in Altadena, which is where we shot it.

I especially enjoyed those brief glimpses of ugly pop art in Oliver’s bedroom.

AM: That was in the script, that was very specific.

AR: It’s McDonald’s, Mickey Mouse and Jesus, and it’s because Oliver is obsessed with the idea of being an icon. Nothing is more iconic than Jesus. In the case of Mickey Mouse, it’s actually Steamboat Willie, which was one of the original Mickey Mouse iterations, and it had just become public domain that year, so we could actually have it up in the house. You can’t have McDonald’s, but you can have the arches. It was really fun to see what we could get away with on his walls. I think I was a little bit indulgent in keeping that in the film, but I’m glad you pointed it out.

As for music, Archie, you worked with Rex Orange County on producing the soundtrack?

AM: Yeah, well, he was a friend that I was just hanging out with, talking to him about the character, and was one of the people I was doing a bit of research with, I guess. As he came to know more about the film, he gifted us this song that he had written for his album, and it feels like it was written for the film. But it was very sweet of him, and it was really useful to have somebody being so open about their career, and the highs and lows of employing friends and loneliness and being on the road and male dynamics, it was really useful to me. He was an incredible, incredible resource.

You’re also credited as a producer on Lurker. What was that specific collaborative experience with Alex like?

AM: Very early on, a comfortability started where we were sharing ideas, or Alex would call me and be like, ‘Hey, what do you think about these two DPs? Can I talk them through?’ I really enjoy working like that, and so then it just became very collaborative. Me being like, ‘Hey, have you cast this part? What about this person?’, or, ‘I know you need a song for this scene. What about if I make a call and do this thing?’

I think it was [producer] Alex Orlovsky that actually mentioned it, ‘you’re doing more than some of the actual producers are doing’. My team flagged it as well, and I was like, ‘listen, I love working, that’s something that I am doing outside of this anyway.’ I was not a part of the conception of this, but it’s something that I always wanted to explore, and being then given permission to be a part of these conversations then allowed me to actively learn and speak to the rest of the producers, Alex, about what was happening at certain points, sit in meetings, be a part of the calls and the conversation that you never really get to be a part of as an actor. It was amazing to be a part of something that you love so much, and have that experience for the first time, being something that I felt so close to.

Did you have long discussions about what Oliver, as a character, actually longs for, fame or friendship?

AM: I initially auditioned for the role of Matthew, and then two years went by, my agent called me and was like, ‘Alex Russell wants to meet you for Lurker.’ I was like, ‘I thought they made that film.’ He’s like, ‘No, they want you for Oliver’, I was like, ‘Huh, Oliver?’ There was such a switch in my head, because when you read a script, you fall in love with a character you initially read, or you see it from their perspective anyway. That felt so scary, to all of a sudden be the subject of a version of affection or obsession, and the person that was cool, and I was like, ‘how the fuck am I gonna do that?’

AR: You didn’t imagine being cool?

AM: No, I didn’t. You’re cool, and you don’t imagine that necessarily. If I were to say to you, ‘Act cool now, for this director,’ you’d be like, ‘Wait, what’s his perception of cool? What does that mean?’ That’s so subjective, and it’s just a very difficult–

TP: You think I’m cool, too?

AM: It’s just a really difficult thing to imagine, to present to somebody. Actually, all the things that the script kind of drew up for me in the first read, a lot of it applied to Oliver. The idea of private and public self, the idea of hierarchy and male dynamics and friendships and this kind of puppeteering thing and masquerading, all of that was happening for Oliver. And then all of a sudden, this new opportunity of making music potentially and performing felt so scary, but also really exciting. That fear, that kind of pulled me towards it.

Archie and Théodore, how did you approach those moments of homoerotic confrontation, particularly the scene in which Matthew wrestles Oliver on his bedroom floor?

AM: We definitely didn’t struggle with it. It was a scene, actually, that was for a second taken out of the script. We both without knowing, messaged Alex, being like, ‘Why the hell is that scene gone?’

TP: ‘We really wanna do that wrestling scene.’ I don’t know why that got cut out. It’s literally just a line that says, ‘and then they wrestle’.

AR: It was the only script notes they really had throughout the process. That wrestling scene was so fun to shoot; we hadn’t decided how the physicality would play out and who would be pinning who, ultimately. I actually think we shot it a couple of different ways, but it became more interesting to me. The obvious way is for Matthew to be on top at the end of that scene. But the more interesting way is that he’s sort of gotten pinned by Oliver, but you know that he’s still the one in control.

It also is not like they’re two closeted guys, it’s implied and actually shown that Oliver is bi, in who he’s talking to and who’s in his bedroom. So it’s not like they’re two straight guys, and they really don’t want to make themselves available to each other in that way. It’s just a way to show what they’re after.

AM: And to speak to the subject of queerness, Alex always describes it as about offerings. Especially in that scene, it’s like, ‘is there something that you want? Let’s put this on the table, would this make it stop?’ Listen, it’s not the thing that either of them is after in this relationship. They’re not looking to fuck, that’s not their thing. It’s not to say that there isn’t a world in which that couldn’t have been on the cards for either of them, in a world where Oliver might have thought, ‘Okay, if I sleep with him, I think he’s gonna give me back the thing’. I don’t know what the version of that would have been for Matthew.

TP: ‘If I sleep with him, will they keep me in the circle?’

AM: ‘Will he want me still?’ It’s a question for both of them, but ultimately it’s not the answer.

LURKER is in UK cinemas now

Images courtesy of MUBI