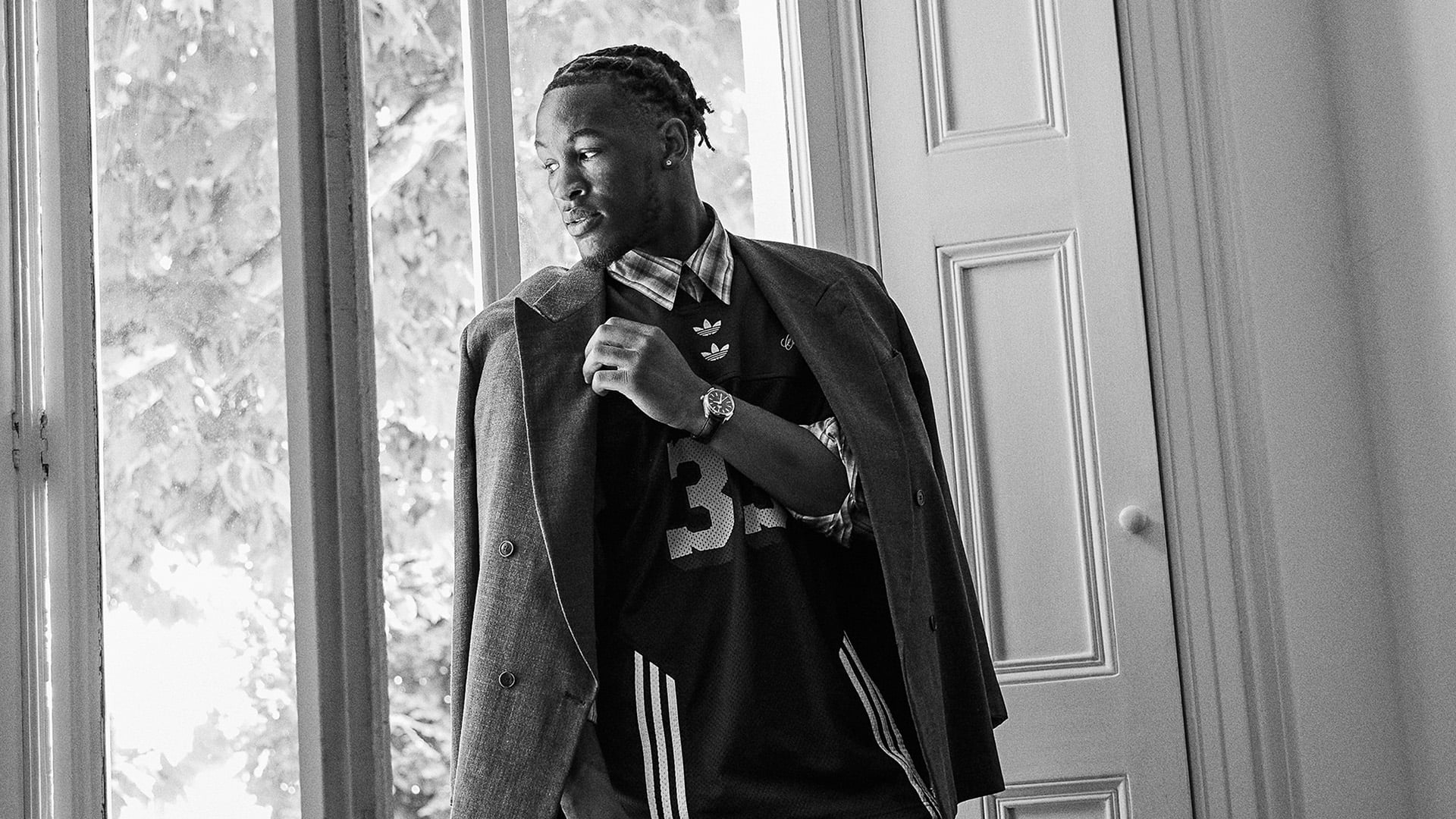

Revered British artist Leon Vynehall soars to artistic heights with his new album, In Daytona Yellow. He talks Japan, experimentation, and essence.

The growth of British electronic music in the past decade has been meteoric. Stigmas towards the genre have long dissipated, with a pantheon of potent producers transforming the landscape into a habitat of growth, development and innovation.

Atop of this burgeoning tree sits Leon Vynehall. The Ivor Novello-nominee is some 13 years deep into his tenure, from his inaugural endeavours dropping left-field house music on underground labels like Running Back and Rush Hour, to completely re-shifting the perception of his artistry with his astonishingly expressive and richly cohesive 2018 debut album Nothing Is Still. This was followed, three years later, by a sophomore record that took his artistic scope to new breadth, melding together avant-electronic tendencies with a post-punk garnish.

Some four years later, Vynehall has shared his third, and most personal, album. The most obvious difference with In Daytona Yellow in comparison to its duo of predeccesors is that the artist uses his own vocals for the first time. Vynehall’s voice is expressive and enduring, used as a technical and emotional tool alike. But the progression doesn’t end there. The album is the most mature music of Vynehall’s career, effortlessly roaming around emotional intricacies and immersive soundscapes, full of colourful contradictions – nocturnal yet bright, sharp yet dreamlike, melancholic yet hopeful.

To concoct this modern masterstroke of musicality, Vynehall convened a cohort of contemporaries, both rising and established. The project bleeds collective spirit, with the array of artists bringing texture, character and depth to the work. There’s regular collaborator TYSON, underground rap savant Jeshi, hugely slept on Birmingham four piece Chartreuse, Czech-Ghanian musician and dancer, and many more.

With this third album proving a career highlight for the much revered Vynehall, he connects with Man About Town, discussing how a trip to Japan kickstarted the album’s creation, the shifting landscape of British electronic music, and walking the line between emotional songwriting and sonic experimentation.

Take us back to your musical roots. Where did you first find your love for creation?

My grandfather, whom we called Pops, played guitar in a skiffle band back in the early 1960s. In New York, he and his friend would play in bars under the name ‘Derick & Eric From England’. He loved country music–Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, and Willie Nelson were his favourites. I would always see him playing his acoustic guitar, so my curiosity for playing music was there from a young age because of him.

I’m also told a story from when I was four years old and my parents got married, that I was obsessed with hitting the keys of a piano at the venue. I began learning the guitar at 10 and started messing around on the drums not long after. I would play music with my friends at school. It all kind of just snowballed from there.

After years of releasing EPs on left-field labels, in 2018, you signed for Ninja Tune and shared your debut album. How did signing with the label steer the direction of your career? How was the process of stepping up to make a full-length studio album?

Ninja Tune was a label I had admired for many, many years. My mum was, and still is, a huge Mr. Scruff fan and would listen to “Trouser Jazz” all the time. So when it came to signing with them, it felt like a full-circle moment. ‘Nothing Is Still’ was also a lot larger in scope than anything I’d done before–there was an accompanying novella and music videos, so doing it on a label with not only a solid reputation, but infrastructure and the means to do the project justice was important.

I had worked on that album for five years. There was a lot of research that went into the story, and sufficient time spent writing the novella with my friend Max Sztyber. I used the text as a brief of how the music should follow, so one thing had to be finished, or nearing completion, before I went onto the next step.

The album was somewhat of a departure from what I’d released previously. The deep-house and techno flavours I was known for weren’t front and centre on this, as the story and overall narrative didn’t ask for it to be that way. It would have felt like an injustice to tell the story solely through a genre that didn’t have anything to do with the time or the people.

It’s definitely the album that has garnered me the most requests for scoring film & TV, which is an area I’ve been working towards moving into for a long time.

How do you reflect on your prior catalogue? Looking back, what does your sonic progression suggest to you about your own artistry?

I’m someone who is creatively curious and eager to learn and discover new things. That could be production techniques, genres, instruments, or philosophical ways of being and approaches to life. I think all good artists use the world as a substance. Your work lives around, and it inevitably comes through in what you create. It’s hard for what you make not to become some sort of diary entry into who you were, or what you were consuming at the time.

What do you think of the description, ‘electronic’ music, within the context of your own work and within the wider direction of the producer scene?

Many young ‘producers’ (I think this word is a far too generic term that’s lost a lot of its previous meaning) don’t know how to play an instrument. Their instrument is the laptop. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, and ‘electronic music’ definitely feels like a fitting adjective, but it seems it’s only applied to people who make Techno, Drum & Bass, IDM, EDM, and the like, when in reality so much of modern music could be classed as ‘electronic music’ if we look at how it’s made.

In terms of my own work, I suppose it fits that definition, but I don’t feel it’s exclusive to it–more like a blanket word that does a fair amount of heavy lifting. My stuff is a hodgepodge of different influences.

How would you define your essence as a producer?

It can be a number of things, dependent on the environment and the people who are within it, but you have to be a non-exploitative Svengali and world builder in your work. If I’m working with another artist or band on their vision, helping to make the music is only half the job. You also have to be a confidant, or an armchair psychiatrist, and someone to corral the project.

Congratulations on your new third album! How are you feeling about the release?

In the best way, I feel nothing. That might sound glum on the surface, but I mean it in the sense that all I haven’t gotten and needed from this record has already happened. I learned a lot about myself in the process. So upon its actual release, I don’t feel the pull of needing external validation from it. I don’t mean that to come across as arrogant, or that I don’t need anyone else’s opinion of it because what I think I’ve done is so brilliant, it’s more that I pushed my self, what I’m capable of, and what I thought I was ever comfortable with sharing for the sake of music and art, than I ever thought I would, and that gives me a sense of strength and renewed validation of self–and should be the whole point.

What’s the story behind the album name, In Daytona Yellow?

All the while working on this record, I had a verse from Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” as a manifesto. It reads…

“Ring the bells that still can ring,

Forget your perfect offering,

There is a crack, a crack in everything,

That is how the light gets in”.

Daytona Yellow is that light, and this record is me stepping into it, cracks and all–hence, In Daytona Yellow.

The album’s genesis is rooted in a trip to Japan and a visit with “master of light” artist James Turrell. How did this drive the direction? Why did it prove consequently influential?

I had already been working on the music and the album’s theme, but seeing James Turrell’s Minamidera piece in Naoshima solidified how I wanted the record to be presented and where it all lived.

At the exhibition, you’re led into an incredibly dark room–you cannot see your hand in front of your face. You sit down against the back wall and are told that the work will reveal itself. Slowly, at the other end of the room, a rectangle of hushed violet hues begins to show. It’s like a portal to the next world. Two lights, one on either side of the rectangle, slowly appear, water falling the same purple light down the side walls. After 10 minutes, the guide who led us into the space returns and invites you to stand up and walk around the room. What was once disorientating and impossible to navigate is no longer. The work has been on the whole time, we are told. It hasn’t changed; you have.

It sounds so simple, but it felt profound in that moment.

It’s a metaphor of highlighting that through periods of discomfort, you are capable of adaptation–perhaps even growth.

I wanted the music to live in that room. The cover photography is meant to be a version of me in that room, with the light pouring in.

From your perspective, how is this new record an evolution from your previous works?

Well, the most obvious thing is that this is the first time I’ve collaborated with singers on my own work, and in doing so, a more traditional songwriting format–albeit through my skewed lens. I’m always trying to grow as an artist, and I enjoy expanding how and what I do. My goal is always to bring forward with me the things I have learned before to help inform what is to come next.

What were the main sonic pull points for the album? What steered its musical direction?

A lot of the musical influences of the album were contemporary artists like Rosalia, Toro Y Moi, Kelela, OPN, but also there was a period of time where I couldn’t stop listening to Lionel Richie – Penny Lover, or Tears For Fears’ ‘Songs From The Big Chair’. Talk Talk, Simple Minds, and Phil Collins also got heavy rotation. Essentially, artists whose approach to ‘pop’ songwriting was from a different angle.

The album walks the line between emotional songwriting and sonic experimentation. How did you find this middle ground? How do the two inform each other?

A lot of the time I like to start songs with sounds rather than melodies, so this can point you in a particular direction from the off, but it’s an interesting way to approach it from a songwriting sense because there isn’t a fixed point at which you’re headed towards, unlike if you have a set of chords there are melodic rules you follow – however loosely.

I can have an idea of how it needs to feel, or what it’s about, but I’m dictated by its emotionality without having to worry about its melodic structure straight away, necessarily. That can come after.

How have you found the process of discovering your voice within the context of more traditional songwriting?

I know, and have always known, that I’m no singer, nor do I want to be, but that it’s ok for me to use my voice when it’s fitting to. I can enjoy the experimentation without judging myself. I can hold a note and write a melody, but I’m no John Martyn, and that’s perfectly fine.

What lies at the core of the album’s thematic threads? What does this body of work mean to you?

Power in vulnerability, and it’s essential part in growth.

Aside from the album, what’s new with you for the rest of 2025?

I’m heading out to the US for DJ dates in October, and doing a big event in London at Earth (Hall) on Nov 7th where I’ll be playing all night and inviting some of the artists from the record to come out and perform. I’m already well into the next record, and I’m also about to start scoring my first feature film–something I’ve been working towards for a very long time.

![Picture of “[Whether Photographing] A Dustman Or The Queen, I Will Try My Best – But, Naturally, The Queen Was A One-Off”: David Montgomery On Capturing Icons](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F12%2FDM-Hero-768x339.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_BXUzDoVpt9tMsB28hbFKcUMT7sik)

![Picture of “It Makes My Heart Swell With Happiness When People Say, ‘[Watching Juice Is] Like [Taking] A Tour Inside Your Brain.'”: Mawaan Rizwan Will Bowl You Over](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F11%2FMawaan-Rizwan-Hero-II.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_BXUzDoVpt9tMsB28hbFKcUMT7sik)