The Texan Academy Award-winner, now leading survival-thriller The Lost Bus, has staked his career on a heady cocktail of belief, faith and conviction. With his new devotional collection, Poems and Prayers – already a New York Times Best Seller – he’s finally ready to share the recipe.

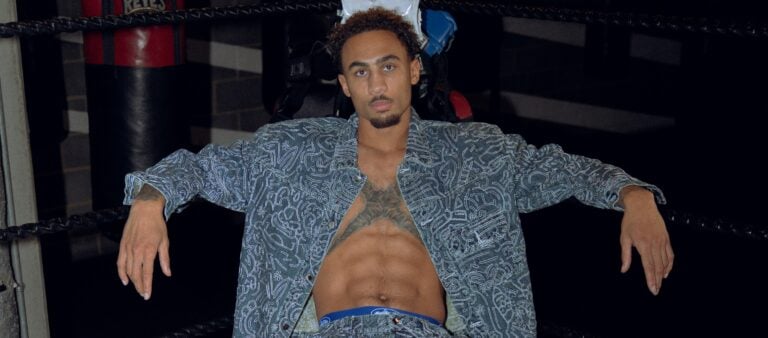

It’s late August, and Matthew McConaughey is perched on the porch of a verdant fish camp in his native Texas. Beside him sits Levi – the eldest of his three children with wife Camila Alves McConaughey, older brother to Vida and Livingston – watching on with quiet admiration. The tableau recalls Mud, McConaughey’s 2012 Southern fable set on the Mississippi, in which a backwater bromance between the fugitive Mud (played by McConaughey) and two boys who discover his weathered boat on the riverbank (Jacob Lofland and Tye Sheridan) unfolds into a lyrical coming-of-age story, culminating in one of his most expansive and widely regarded performances to date. Today, though, there’s no fugitive tension – only the easy harmony of family, and a budding bond between father and son. In just a few weeks, The Lost Bus will premiere at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival, marking the first time the McConaughey men have shared the screen.

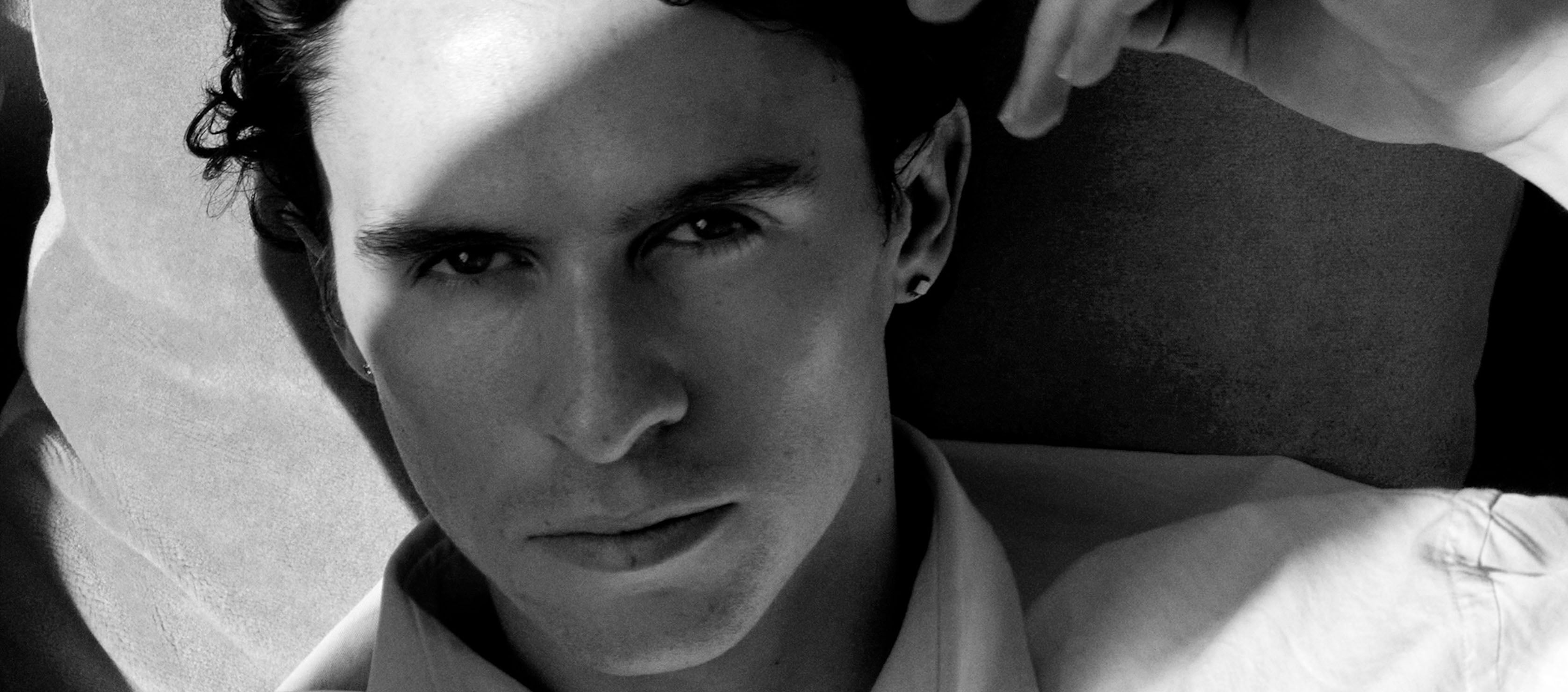

“Hopefully, we get a little rain soon,” the 17-year-old interjects, his shaggy mop of brown curls already a fixture in the fashion world after a Dior campaign and a turn on the red carpet at London Fashion Week put his name into circulation. His next supporting role, in Way of the Warrior Kid, set for release in 2026, only cements a trajectory that shadows his father’s own – McConaughey senior reportedly slipping onto set with words of encouragement, something he has never been short of.

For the Oscar-winning actor, the moment is rich with symmetry. McConaughey has long argued that faith, persistence and timing count for more than raw talent, though he’s hardly short of that either. It’s a sentiment that has carried him from his 1993 cult debut role in Dazed & Confused through to breezy rom-coms like 2001’s The Wedding Planner and 2003’s How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, and the so-called “McConaissance” of the early 2010s – Hollywood’s term for his leap from perennial heartthrob to authoritative dramatic force. After a self-imposed two-year hiatus following 2009’s Ghosts of Girlfriends Past, he returned with an extraordinary run: an acclaimed turn in 2012’s Killer Joe, followed by 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street and Dallas Buyers Club (the part that won him the gold statuette and for which he shed 22 kilograms), before True Detective and Interstellar the following year.

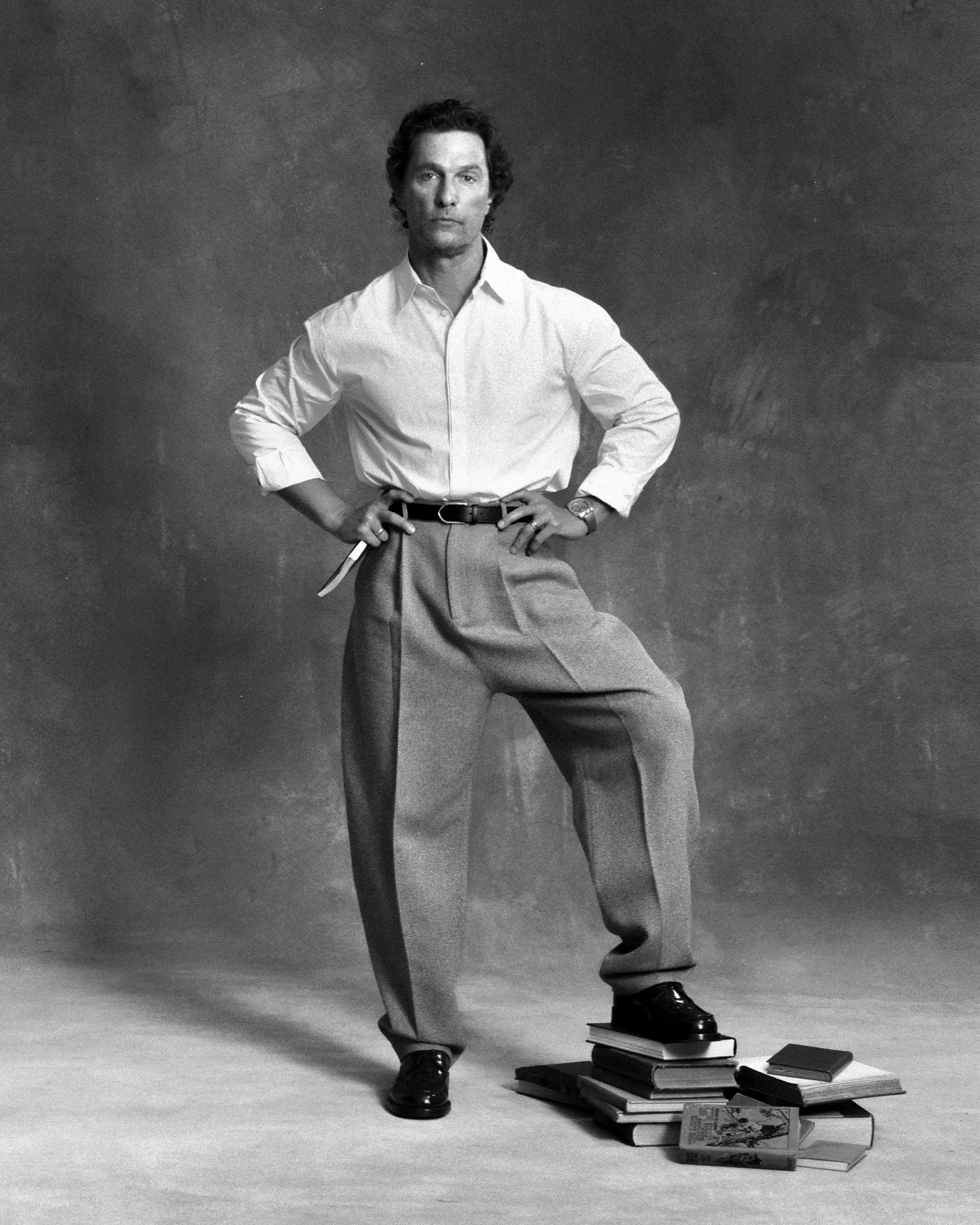

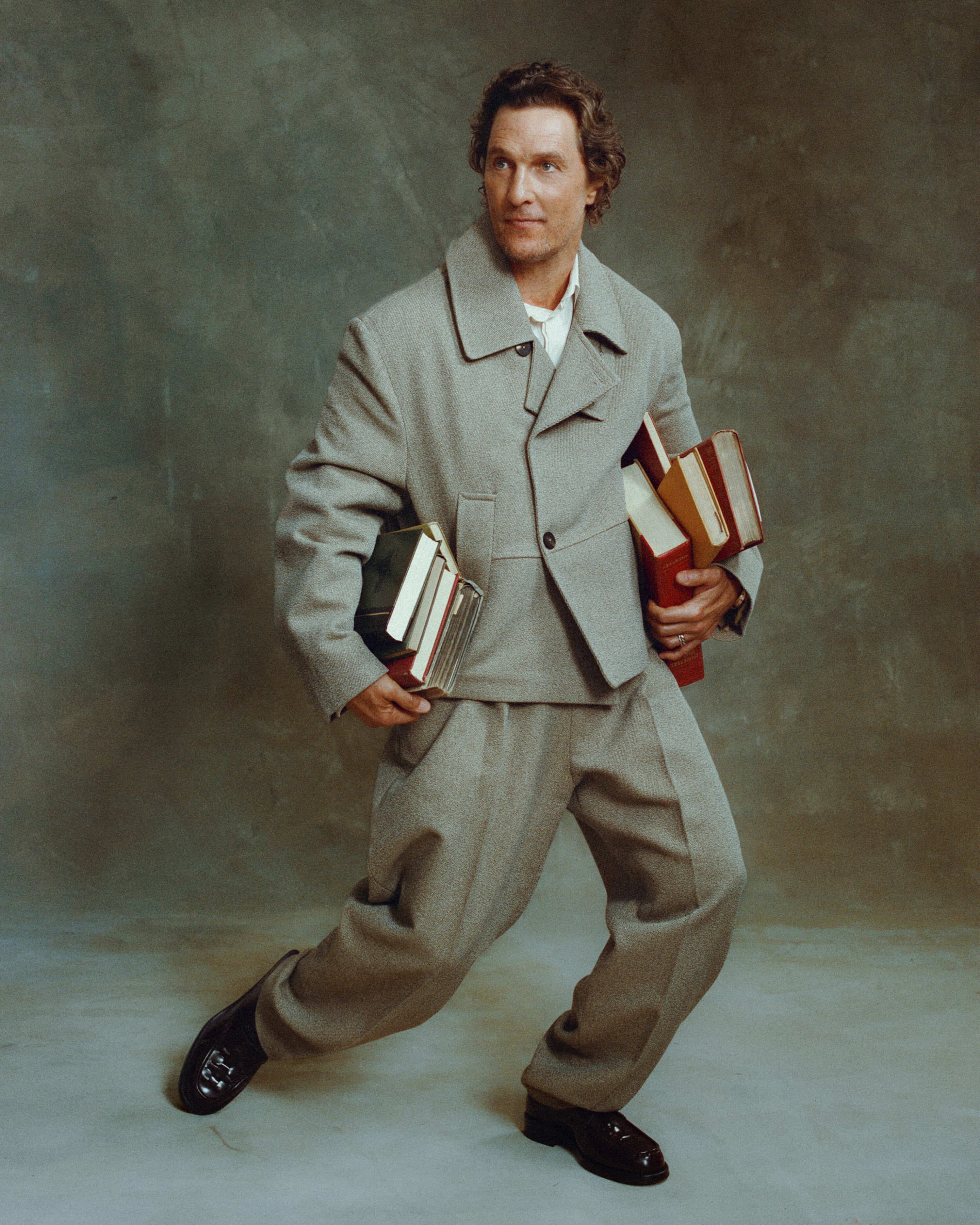

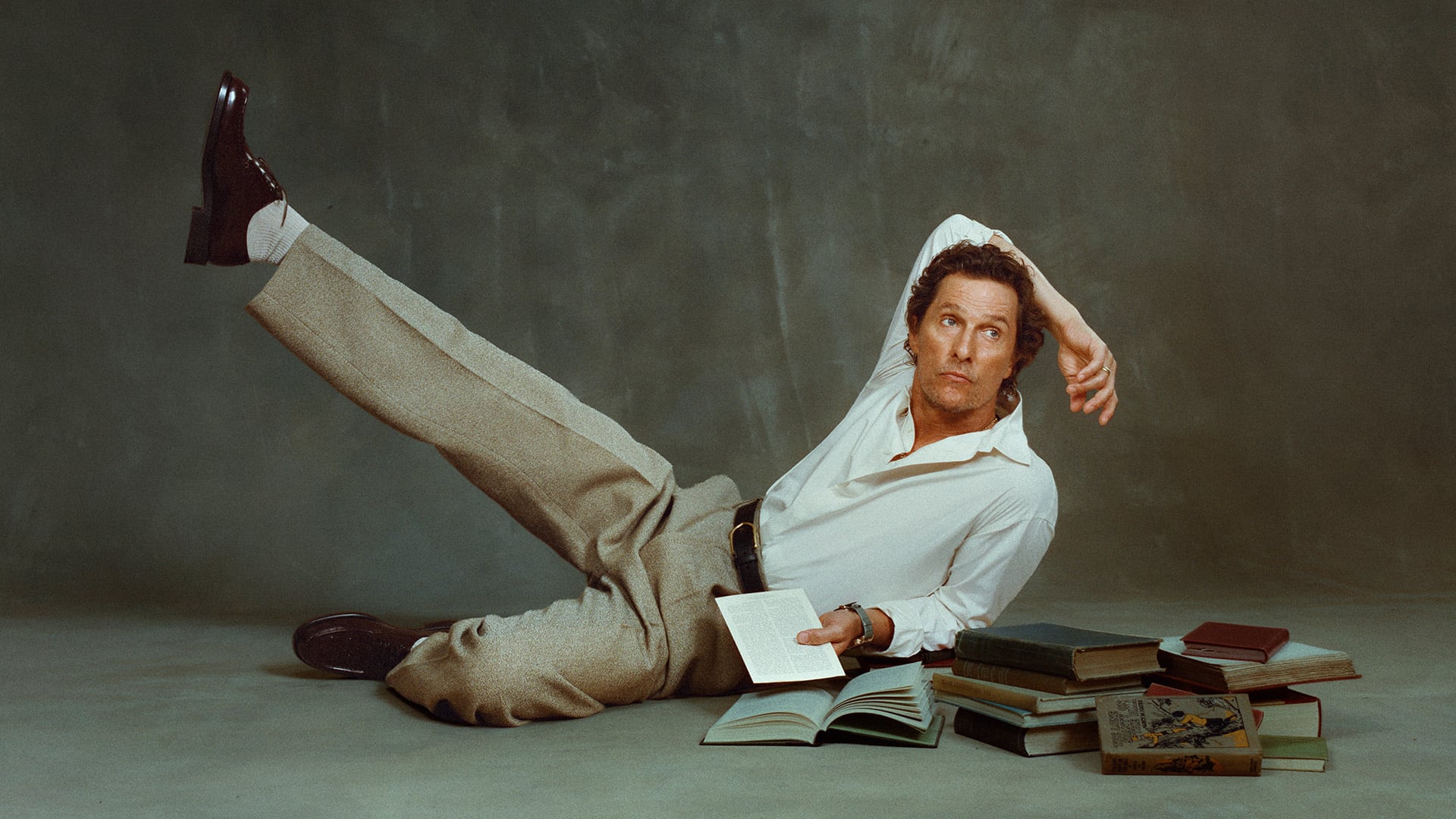

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS

“Hope is not really a plan,” he tells Levi, his oddball intensity kicking in, offering a glimpse of the kind of generational wisdom fathers like McConaughey pass down to their sons. “Hope doesn’t come with a path. It doesn’t come with an owner’s manual. It’s more like: ‘I hope it happens.’ And if it does, well, you just got lucky. But belief is different. Belief says: ‘Yeah, I hope it happens, but I can also see how it can happen. I see a pathway. There are constructive things I can do to make that belief come true.’ Belief is the engine that makes dreams come true.”

Now, with his new poetry collection Poems and Prayers, McConaughey is intent on passing that philosophy down, not just to his children, but to anyone willing to listen. It’s a creed that’s served him well – so well it makes you want to etch his words into your skin as a permanent reminder. But that’s what Poems and Prayers is for: a bible to his way of life, a rhythmic extension of the wisdom first mapped out in 2020’s Greenlights, his bestselling memoir that has sold over six million copies.

That same unwavering faith anchors his latest role as Kevin McKay in The Lost Bus. The disaster-thriller from director Paul Greengrass (The Bourne trilogy, Captain Phillips) documents the true story of a devoted bus driver who, alongside a schoolteacher played by America Ferrera, fights to save a busload of children during the 2018 Camp Fire – one of the deadliest wildfires in California’s history. Levi, fittingly, plays Kevin’s teenage son. Under Greengrass’s unflinching gaze, the terror is tangible: flames closing in, panic rendered through chaotic camerawork that feels plucked from the event itself rather than staged for drama, illuminating the devastation wildfires continue to inflict year after year. Yet it’s Kevin’s determination, channelled through McConaughey’s strikingly visceral performance, that emerges the fiercest lifeline – a belief that survival is always a possibility, despite the odds seeming insurmountable.

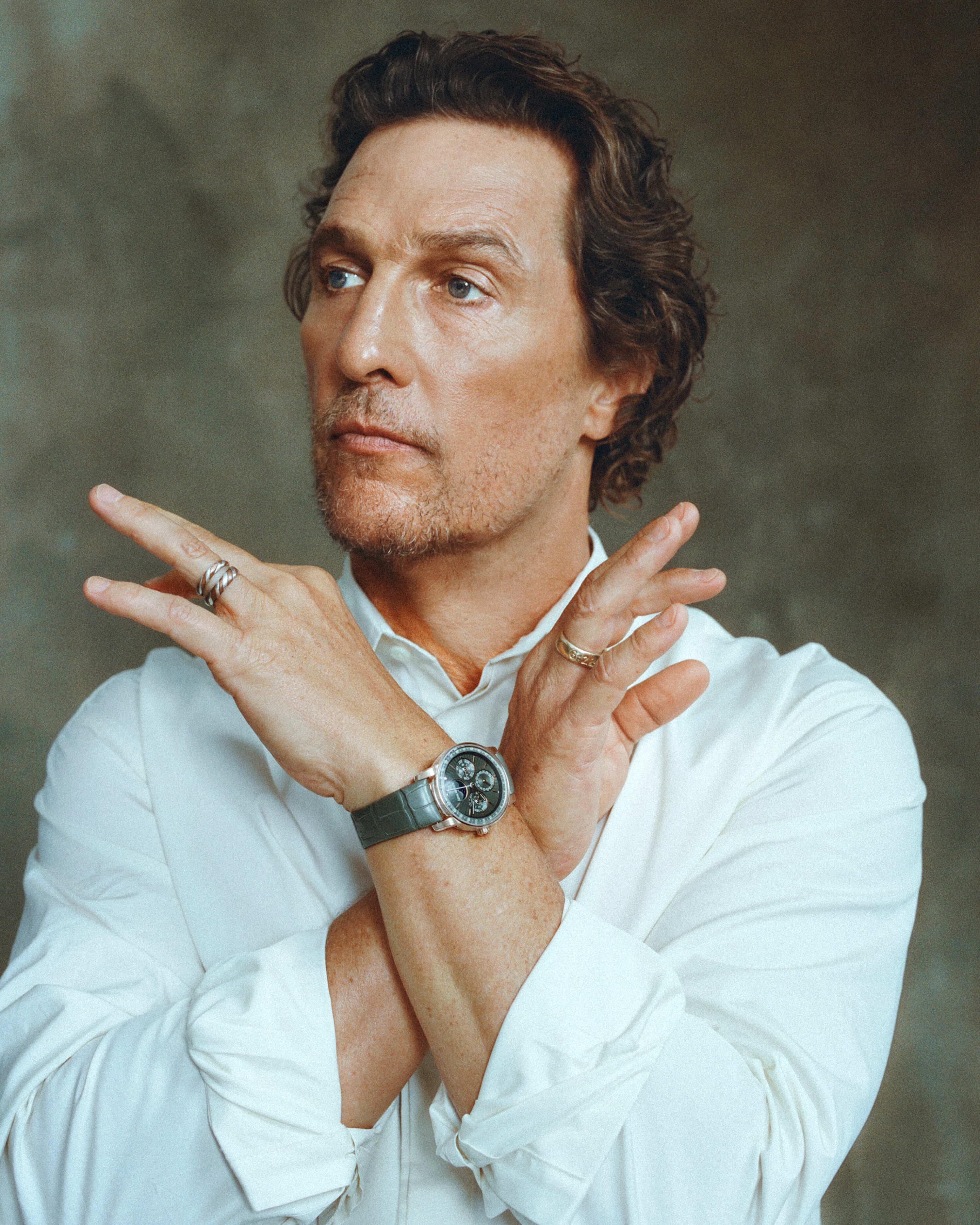

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS; watch AUDEMARS PIGUET

“Belief is in short supply, and I understand why. When you look around the real world, it can be tough to find something to hold onto,” McConaughey says. “But we don’t need to quit believing, because if doubt wins, we all lose.”

And so, father and son trade lessons: McConaughey passing down the hard-won truths that continue to shape him as an actor, as an author, as a father and as a husband.

Levi McConaughey: I have some questions for you.

Matthew McConaughey: Great. Hopefully, I have some answers.

LM: You’ve had decades in the public eye as a movie star, and then surprised people by becoming a best-selling author with Greenlights. With Poems and Prayers, what do you want people to understand about you now?

MM: I struggle with doubt, and I’m tempted to be cynical sometimes – just like I think all of us are – and I’m not ready to lay down and raise the white flag and say, ‘Oh, that’s just how it is.’ So I’m really chasing down belief. I don’t want to quit believing in me, you, God, our potential, and a better humanity. And so Poems and Prayers is a book full of poems and prayers that are places to seek dreams. Poems are a wonderful place to try and make sense of the world through dreams without rules, and a place where you can dance with ideals. When a good word and an aspiration rhyme, it’s even easier to digest and more fun to listen to, and that’s what I hope people get out of this book.

LM: What do you mean by ideals?

MM: Ideals: the way it ought to be. In other words, aspirations. I’m aspiring to be a better man, a better father, a better husband, a better actor. We get those from ideals. We project into the future and go, ‘What do I need to do to get there? Maybe I’m not hitting the mark that I wish I could hit in life?’ Are we hitting the mark as humanity? I don’t think we’re hitting the mark, and it’s ambiguous where people should go to get a bit of a roadmap. What’s something we can all agree on that’s a good way for living, that’s a good rulebook for how to live, you know? And if you’re not seeing it around you every day – which I’m not seeing as much as I wish I was – I’m like, ‘Hey, pump this up a little bit, get those dreams down, and make them become real.’ That’s why I went to Poems and Prayers.

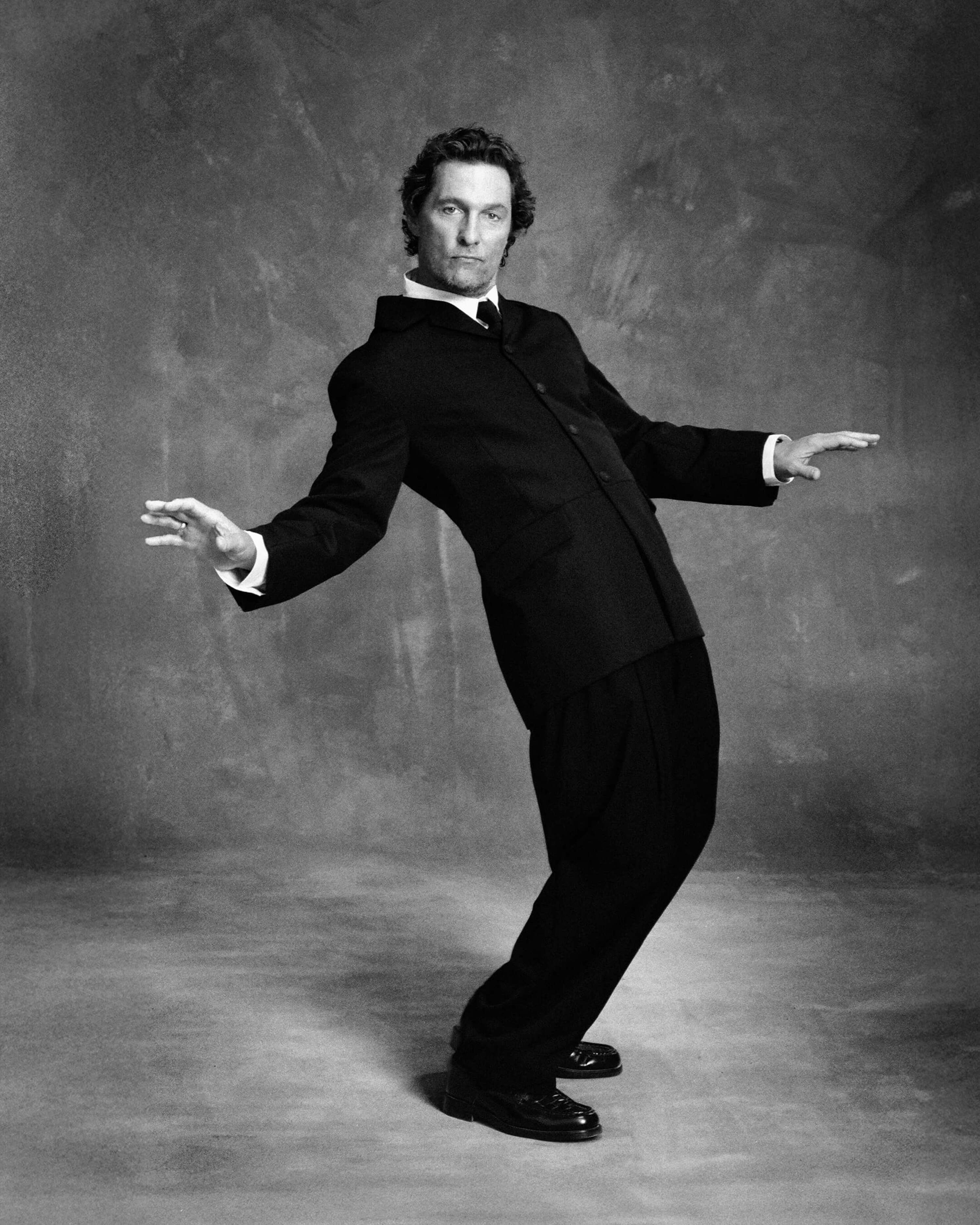

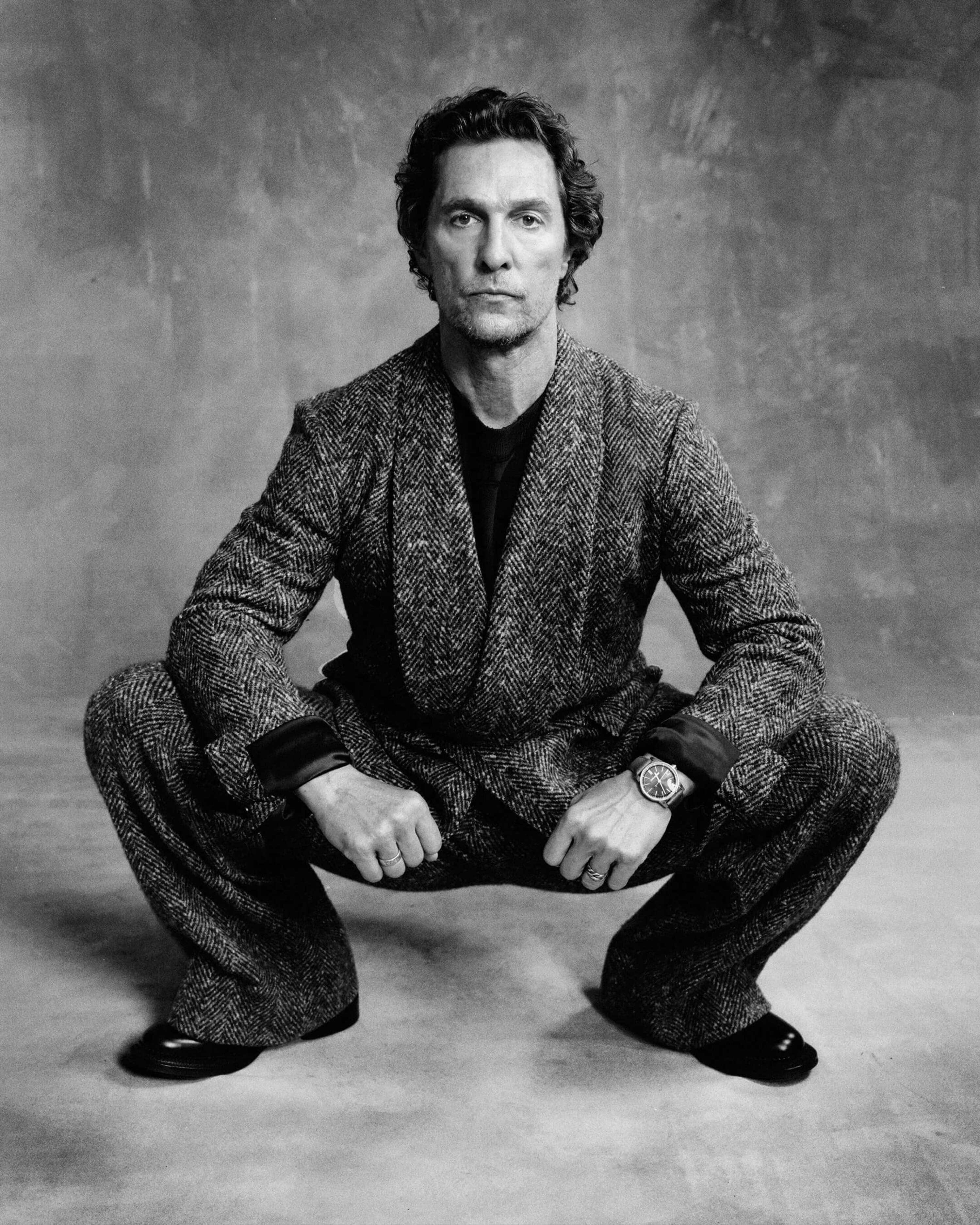

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS; watch AUDEMARS PIGUET

[Poems & Prayers], for me, is like, ‘Hey man, let’s lay it on the table, McConaughey.’ Even the stuff that’s not all happy, jolly, and cool.

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS; watch AUDEMARS PIGUET

LM: So, do you feel like Poems and Prayers is a little bit like bits and pieces of that roadmap?

MM: Yeah. It’s spiritual reminders. It’s artistic reminders. It’s ways of seeing, ways of perceiving, ways of desiring, so we can understand the way to behave. Because I don’t think we’re perceiving correctly, which means we aren’t desiring correctly, which means we aren’t understanding correctly. And if we don’t understand correctly, we can’t act correctly.

LM: It sounds like I need to read Poems and Prayers.

MM: I hope you do.

LM: Was there a part of yourself that you felt nervous putting out there? I mean, I know you felt that with Greenlights. There’s a lot of personal stuff in there.

MM: Yeah, and there’s some personal things in there that I intentionally made very short. Because if I explain them – some of those things in Greenlights, like being blackmailed early, sex, my first time – I knew those were going to be the headline. And I didn’t want people to see that, because that’s not what the book’s about.

I found myself being cynical and looking around at the evidence in the world and going, ‘Nah, I don’t see enough to believe in. I’m not believing.’ And I’m going, ‘Whoa, that’s an early death. Why? You’re still alive,’ you know?’ And so [the book] is for me too, when I say ‘we’ in Poems and Prayers that includes me. I’m not making As in all these classes. So where am I evangelising? Am I sermonising? Sure. But I’m also talking to myself. I’ve got work to do. You know, we all do. I have a lot of people come to me with these same questions that I have. And so I’m sharing it through Poems and Prayers.

LM: I think so much good stuff can come out of things that are meant for other people, but mostly they come from your own necessity. You know what I mean? Like, it’s not, ‘Oh, I’m writing this because of other people.’ It’s, ‘I’m writing this for myself and sharing it with other people.’

MM: Look, I think at the end of the day, it always has to be personal if it’s going to have all-access and more people can understand it. I didn’t set off writing my first poem when I was 18, thinking, ‘Oh, I think I want to publish this one day.’ I’ve been writing things all my life, and then I gathered them and thought, ‘These were all deeply personal and, you know what, they sound like they’re putting up a mirror to what I hear a lot of my other friends and even strangers talking about, what they’re struggling with. So I thought, ‘Let’s share them.’ Maybe we can go, ‘Oh, you too? Yeah, me too.’

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS; watch AUDEMARS PIGUET

LM: Is it easier to be honest on the page than it is in person?

MM: Oh, sometimes, yeah [laughs]. You know, I’ve shared things in Greenlights that your mother – my wife Camila – comes and goes, ‘Oh, so that’s what you’re talking about’ [laughs]. ‘Now I understand more about the man I’ve been sleeping with for 19 years.’ And that’s part of what writing is, but even this book, for me, is like, ‘Hey man, let’s lay it on the table, McConaughey.’ Even the stuff that’s not all happy, jolly, and cool. Some people call that being more vulnerable. I don’t know if that’s the right word for it, but share it, because we all have similar struggles. And again, step one of evolving is admitting that and sharing that. You know, I’ve been more interested in that African proverb about sharing your struggle, sharing your problem, sharing your doubts with community, friends, and family. When you share them, everyone can then have a dialogue and see each other in themselves. And that’s how you get past more challenges. So Poems and Prayers is partially sharing those.

LM: What is the first poem you ever wrote that you still keep?

MM: So, the first poem I ever wrote… I’m not going to include the very first poem that I signed my name to, which I didn’t write, but I did win the middle school poetry contest for. That was an Anne Ashberry poem that my mum, your grandmother, fully convinced me to sign my name to. She said, ‘If you believe in it, if it means something to you, then it’s yours.’ And since I’m that far down the story, I’ll go ahead and tell it. The poem was: ‘If all that I would want to do would be to sit and talk to you, would you listen?’ And mama goes, ‘Write that for your poetry contest.’ I was like, ‘But it’s not mine. It’s Anne Ashberry.’ She goes, ‘Yeah, but you understand it?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I understand.’ She goes, ‘Yeah. Does it mean something to you?’ I said, ‘Yeah, it’s beautiful. It’s like, sometimes you just want to talk to somebody. Sometimes you just want someone to listen.’ She goes, ‘Yeah, write that.’ I go, ‘And sign my name to it?’ She goes, ‘Yeah, it’s yours.’ I took home the blue ribbon. I won the middle school poetry contest. That was full plagiarism. So that was the first one I wrote. Let’s go ahead and stick with that story – the first one, at least, I signed my name to [laughs].

LM: Who are some poets you look up to?

MM: Oh, look, I think some songwriters are poets. I think Emerson [Hart] is a poet. Rumi. [John] Mellencamp in the ‘90s was a real poet for me. [Bruce] Springsteen’s a great poet. Those are some off the top of my mind. There are others. I think philosophy can be poetry. I even have some poems in here that do not rhyme. They just pose both sides of a question. Like one of my poems, “Heaven or Not”. It’s all about misery in this world, with or without a heaven, believing that there is a heaven and something to aspire to and believing that what we do here in this life has to do with whether we get there. Even if there’s not a heaven, that will get us unstuck, and it gives us the best chance to get out of our misery here in this life, heaven or not. And that’s not a rhyming poem, but it’s a beautiful question and a beautiful thing to consider. So, we’ll consider it poetry.

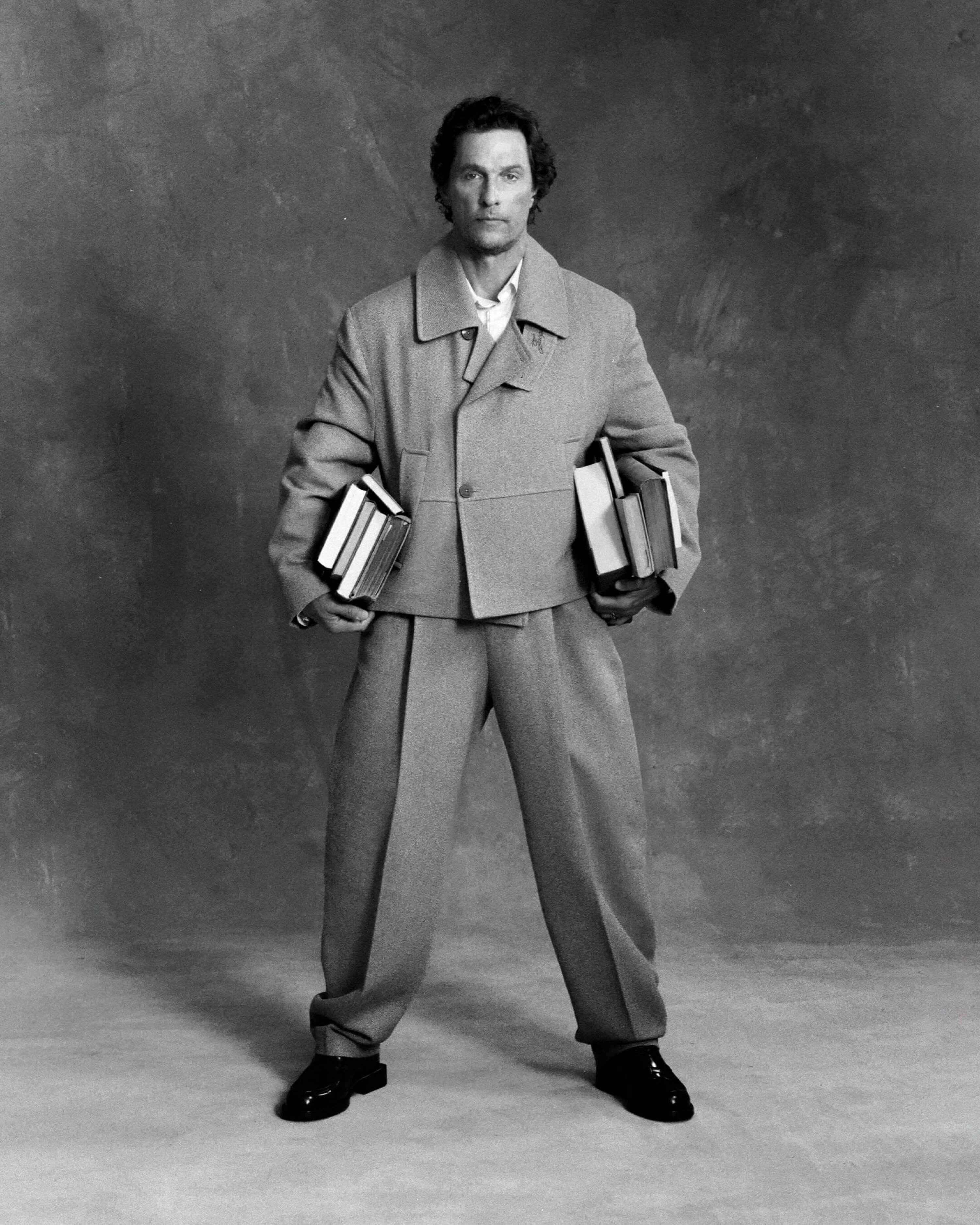

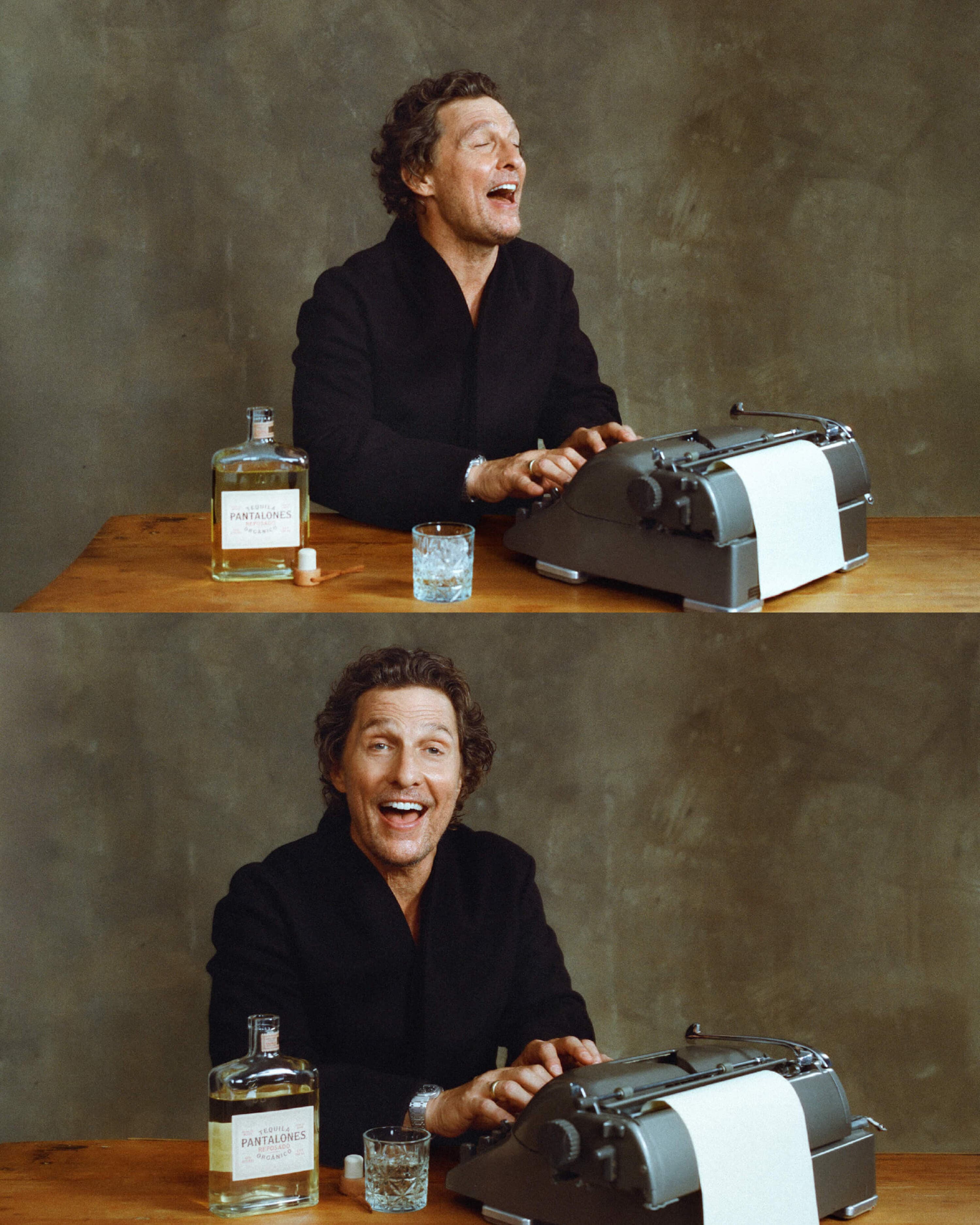

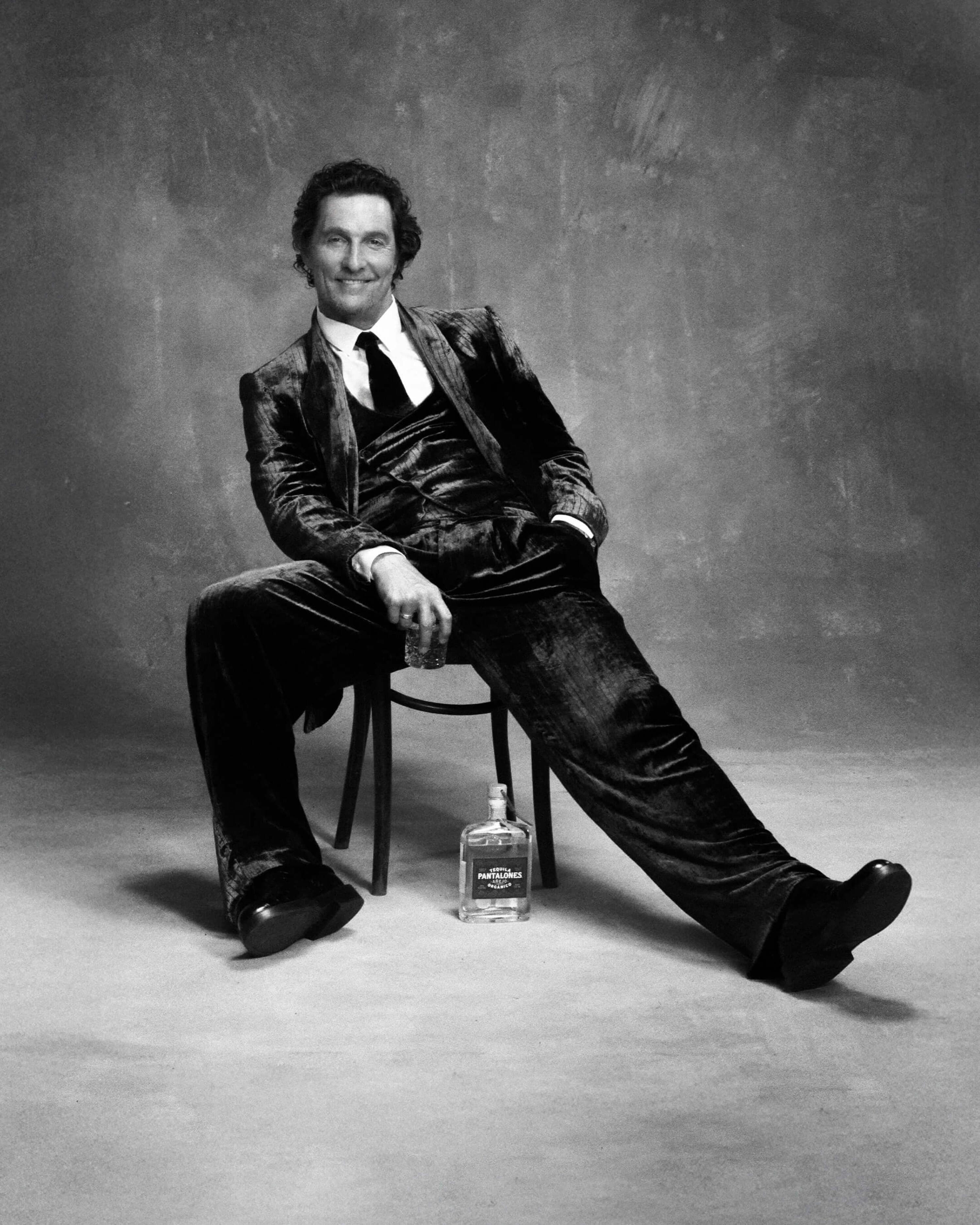

Matthew wears all clothing DOLCE & GABBANA; watch AUDEMARS PIGUET

LM: You described this new book as faith-filled but also hilarious. How do you hold reverence and irreverence in the same hand without one undermining the other?

MM: I’m a big believer in humour. Humour is actually not only a great way but a chosen way to share reverential things. It makes it so it’s not like giving advice. It’s not like I’m talking at you – I’m talking to you. I’m not telling you what to do. Humour unlocks a lot of wisdom and also unlocks us to receive things. They’re not in opposition. And I think, actually, humour unties so many knots of crises. Because nobody likes to be told what to do – I know I’m the last guy who likes to be told what to do. So if I’m sharing a story or someone’s sharing a story with me, or a poem in Poems and Prayers, and inside of it they’re going, ‘I’m talking to you, but I’m talking to me too.’ That makes you go, ‘Oh, okay, now we’re talking about the human condition.’ You’re in on it, we’re laughing at this, we’re all in it. Why not laugh at it? When you laugh at something, when you find humour in something – even a crisis – that doesn’t mean you’re giving the crisis no credit. It means you’re just admitting, ‘This is a crisis, we’ve got to figure this out, so we might as well have a giggle on the way, because, shit, how’d we get in this predicament?’ You know what I mean? It doesn’t mean you care less. It just puts a little sugar on it, and the broccoli is candy. That’s part of what humour does: it makes the broccoli candy.

LM: When you’re giving me a teachable moment or I come and ask you for advice and you maybe bring up a story from when you were younger that’s kind of funny, when I’m already coming in feeling a little bit down on myself or unsure or confused, and then you add in humour and we can both laugh at it, that already takes the initial nervousness or uncertainty out of it. Those stories stick with me because they made me laugh, right?

MM: Humour is a great, wonderful tool. I think it’s almost necessary for teaching, for learning, for surviving.

LM: Facts. It would be so boring if everyone just didn’t like humour.

MM: Imagine a world without giggles, smiles, and chuckles – or big, just laugh-out-loud funny. One of me and your mum’s favourite sounds through the years with you kids is hearing the three of you in another room or downstairs just heckling and laughing loud. It’s such a beautiful sound to hear your children’s laughter. And like I said, even when sometimes we’re having a bum day and we cannot seem to get one in a row of anything, to sit there and go, [laughs] ‘What hand did I draw today? Are you kidding me? What the hell?’ To laugh at it just takes a little pressure off our shoulders. To think, ‘I’m going to laugh at this rut I’m in, because I think it might help me get out of this rut.’

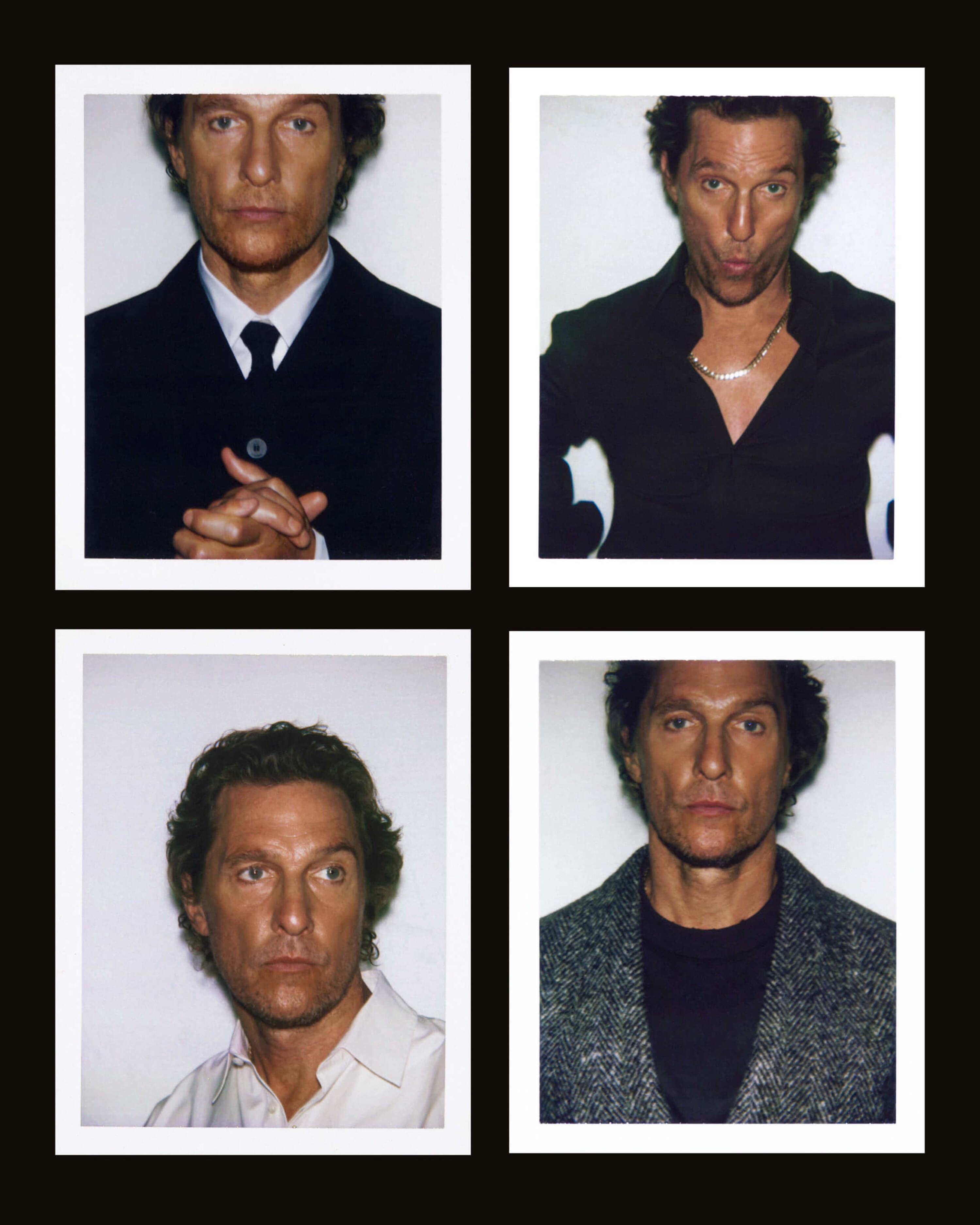

(Top & bottom left, top right) Matthew wears shirt JACQUEMUS. (B ottom right) Matthew wears all clothing DOLCE & GABBANA. Opposite: Matthew wears shirt JACQUEMUS

LM: What’s the difference between what you believed at 25 and what you believe today?

MM: Oh, the difference is marrying your mother and then having y’all kids. At 25, life was a one-way ticket. ‘Hey, want to go to Paris tonight?’ ‘Shoot, yeah. Let’s go. Put a backpack on, head out.’ ‘When do you want to come back?’ ‘I don’t know – when I get back.’ But with kids, y’all as dependents, you get a more peripheral vision of the world, because no matter if I’m with you or not, as your parents, we are carrying you with us and we’re responsible for you. So you always have to have a proverbial return ticket in your life. You can’t just head out on a whim and come back whenever you get back. And that’s a great privilege and responsibility of being a parent. I would say you think more towards the future. I know I do. I think more towards the future. You live more for the future as well. And that comes with, I think, marriage and especially having children – much more so than at 25.

LM: How much of your faith comes from lived experience versus something that you were taught?

MM: Oh boy, that’s a good one. I’m not quite sure. Going to church on Sundays or saying grace before every meal became ingrained rituals. Even when I was young and not really listening to the preacher, just sitting in the pew, hearing a sermon, songs being sung, fellowship on a Sunday morning – no matter how late your Saturday night was – it reminded me to bow, tend, and remember we’re at best number two. That’s humility. Sunday is about humbling. I think it can be a reminder for anyone – religious or not – a day to rest, give gratitude, and humble yourself. Experience has also taught me compassion, forgiveness, grace, courage, even judgment. Humility, too, which in full faith leads to surrender. I’m not there yet. Pride gets in the way, but that’s where I am in the process. I try to carve out time – on Sundays and through the week – to notice beauty, multiply it, make the positives plural and the negatives singular. Not denying the negatives, but blocking their path. That practice shapes my optimism. When I act in more divine ways, the world responds, and roads open – more greenlights in my life.

LM: What surprised you most about working with me on The Lost Bus?

MM: Well, there were two surprises. One was early on when you first came to me, and I told you what the story was about. Afterwards, you were like, ‘So how old is this son of yours in the movie?’ And I said, ‘He’s like 14, 15, 16.’ And I saw that little twinkle in your eye. That’s all I said, because I wanted to see if you were just in a passing whim or whatever. And then you said, ‘Well, can I read for it?’ I was like, ‘Yeah.’ And I didn’t do anything about it. You came to me two more times after that.

Matthew wears all clothing EMPORIO ARMANI

LM: Three more times

MM: On the third time, you said again: ‘Can I read for [the part]?’ And I said, ‘Okay, this is on his mind. He wants this.’ So I recorded you reading it, and I thought you’d be good. You were. That was the first surprise: that you pushed three times to be able to read. Then the next surprise, which was a beautiful surprise, was that on the way to your first day of work, we were driving together and we’d been talking about how to approach, how to study, how to try to find character, etc, etc. All the talk. But now it was time for action. We were going to set, and all the lessons, teaching or prep was done. If you ain’t got it now, you ain’t got it. I remember driving to work that day, and you had a steely look. You were not looking at me. You weren’t asking any questions. You were locked in, kind of looking out the window. We listened to music. We didn’t talk about the scene. You didn’t want to talk about it. You took ownership. You were like, ‘Yep, it’s game time.’ I could tell by the look in your eye, you were thinking, ‘I don’t need any more advice. Don’t hold my hand. Let me walk my own path now.’ That was a surprising but very cool moment for me, as your dad and as an actor. You were very present in it. You also made yourself very directable by [The Lost Bus director] Paul [Greengrass]. And as we played with scenes and changed things up, you rolled right with it. Those are the two surprises for me.

LM: What’s one thing you hope that I see in you that has nothing to do with being a dad?

MM: Do everything you can to get to know yourself and be able to be yourself. There’s no better mortal person in the world to know better than yourself. Only when you know yourself really well can you find a track and be what somebody else is looking for. Then you have that discernment. You are who you are. You not only go after what you want, but you draw things that are true for you, to you.

LM: That’s a good one. Looking back at the ‘McConaissance’ era, was that true reinvention or just the world catching up to who you were becoming as an actor?

MM: I think it was just me getting the opportunities. I had been looking and feeling like that’s the kind of dramas I wanted to do for a while, but I didn’t have the chance. So I wasn’t sharing any of that work. I’m not saying that if I’d got those same roles 10 years earlier, the world would have reacted the same. No, I think I was a different man. I was also coming out of a real struggling time where I didn’t have any work, where I was questioning what I had done, wondering if I’d written myself a one-way ticket out of Hollywood. [After] fighting through that time, I was hungry. I was coming out with fangs, man.

LM: What was the first thing after that?

MM: I think it was Lincoln Lawyer or Killer Joe. And then it went, Magic Mike, Mud – The Paperboy was in there. And then I started losing weight – Wolf of Wall Street, Dallas Buyers Club, then True Detective. That was kind of the run. But look, a reinvention? I didn’t come up with a new invention. I’d say it was a discovery. Definitely. I think that term, ‘McConaissance,’ was the rest of the world, or my peers in Hollywood, going, ‘Oh, this is a discovery of a new McConaughey we hadn’t seen.’ Now, I thought it was always there. So I don’t think it was an invention. But timing, who I was at that time, how hungry I was, how much I needed it, the price I almost paid to get it without the guarantee of ever getting it. I felt I had it in me the whole time, but it was just the right time for it to come out. The right roles and the right stories. And a lot of very interesting things came my way. I was working with some very interesting people and doing some roles that – like them or not – you were going, ‘Whoa, okay. There’s some identity there. There’s something.’

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS

LM: Teaching, which you do at University of Texas, has made you into a mentor, helping to forge new generations of legacies. How has being in the classroom changed how you view your own legacy?

MM: Oh yeah, good question. Because, you know, I had an idea for this Script to Screen class for a decade before I got the confidence to actually go, ‘Hey, let’s make this into a curriculum.’ And part of the reason I didn’t have the confidence for 10 years was, I guess, I still kind of felt like I was a student. I wasn’t confident that I had enough experience that was worth telling. I remember what led me to start the curriculum was I started talking to students about film and advertising. I would say stuff that was really basic, that I thought, ‘Well, of course you understand this, but let me repeat it.’ And they would go, ‘Oh, wow.’ And I’d go, ‘Oh, wow – you didn’t know that?’ ‘No.’ And I’m like, ‘Oh, I inherently have some experiences that have given me knowledge that’s worth sharing, that I’d been taking for granted, that I didn’t have back then, and it’s worthwhile to these students.’ So to be able to come in and have the confidence to go, ‘I’ve actually got experience and knowledge to share that can help these students along the way to understand the craft,’ to be able to technically teach like that and have something worth teaching, and to be able to have experience that I could share – that’s a new chapter for me. And again, I had the idea when I was 40. I didn’t start the class until I was like 48. I wouldn’t give myself enough credit to understand that I had something worth teaching.

LM: Your book, Greenlights, has offered advice and help to millions of people around the world. What’s one piece of advice that you’ve been told that’s always stuck with you?

MM: There’s many. I’ll pick one, though. And this one is: ‘In my view, I’ve had thousands of crises in my life, and most of them never happened.’

LM: [Laughs] Yes, sir. John?

MM: No, it’s not [American basketball coach] John Chaney. Actually, it’s Samuel Monroe Wills. He’s my Alabama friend. It was his great-grandad.

LM: Really? That’s cool.

MM: Don’t create drama, man. It’ll come.

Matthew wears all clothing JACQUEMUS

LM: Okay, I feel like this kind of ties to a little bit of what you’ve said. You talk a lot about never quite reaching the goal. What’s something you still haven’t figured out – as an actor, author, father – no matter how many years or miles you go?

MM: I haven’t figured out how to 100 per cent, 24/7, be in that solely subjective spot where I am the passenger with myself. So in it, the story, and the character that I don’t even recognise that there’s anything fictional going on, that we’re on a set, that this is actual writing. Just in it, and it unravels in real time, and all of a sudden you look up and go, ‘Whoa, that was magic.’ So, becoming almost unconscious in that. It happens sometimes, and every artist knows this – it’s a beautiful, blissful feeling. But boy, to be able to do that and stay in it when you need to, to click that on and off, that would be awesome [laughs]. But it is not achievable for me yet.

LM: [Laughs] Yeah, getting there is something special and beautiful.

MM: Keep chasing it. It’s fun.

LM: Yeah, I mean, the work to get there – you’ve said this before – where it’s no longer work, but…

MM: It’s play.

LM: Exactly, which is what’s fun.

MM: Thanks, Man About Town, thanks, Levi. Love you, babe.

LM: Love you.

Photography

Max MontgomeryStyling

Luke DaySet Design

Po LinPhotography Assistant

Gabriel LloretStyling Assistant

Olly CookFashion Film and BTS Video

Naive StudioVideography

James RogersVideography Assistant

Will DeanEditor-in-Chief

Luke DaySenior Editor

Andrew WrightArt Director

Michael MortonProduction Director

Lola RandallJunior Art Director

Natasha Lesiakowska

![Picture of “When We Were Developing Series [2], We Were Very Conscious Of The Live Debate About What It Means To Be British”: Tom Hiddleston On The Night Manager’s 2020s Comeback](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2Fdigsfo-768x338.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_GwYtxMeHtoBZdDSHj1tcpGrG3Czy)

![Picture of “[The Bridgerton Press Tour] Is Like Being On Some Sort Of Hallucinogenic Drug”: Luke Thompson Is Next In Line](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F01%2FLUKE-THOMPSON-hero-768x339.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_GwYtxMeHtoBZdDSHj1tcpGrG3Czy)

![Picture of “[Whether Photographing] A Dustman Or The Queen, I Will Try My Best – But, Naturally, The Queen Was A One-Off”: David Montgomery On Capturing Icons](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F12%2FDM-Hero.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_GwYtxMeHtoBZdDSHj1tcpGrG3Czy)