As his “art project”-meets-film – Peter Hujar’s Day – hits UK cinemas, the storied British actor guides Fehinti Balogun through immortalising an ordinary 24 hours in the extraordinary New York photographer’s life.

No one eats a cupcake like Ben Whishaw. Or, more precisely, no one eats a cupcake like Charmaine, Ben Whishaw’s character in short film O Holy Ghost – Mark Bradshaw’s 2019 study of spirituality, co-led by Whishaw alongside a pre-House of the Dragon Emma D’Arcy and Down Cemetery Road’s Fehinti Balogun. Three words are all Charmaine utters in that particular scene, atop a water tower, after he leads a transcendent religious ceremony. His consumption of the iced homebake does the talking instead.

“You make the banal and the mundane quite epic,” Balogun tells Whishaw, six years on, over Zoom. “That [scene] will stick in my head for maybe the rest of my life. It was such a clue into that character’s life.” It’s just over two weeks shy of Christmas Day when the pair convene for Man About Town, and three weeks until the UK theatrical release of Whishaw’s current project – a turn as foundational New York photographer Peter Hujar in Ira Sachs’s Peter Hujar’s Day. “You can tell so much about a person by the way they eat,” Whishaw concurs. The 45-year-old has been a touchstone British actor for over two decades, but to this day, it’s the quotidien that lights him up the most. “I always find undramatic things peculiarly fascinating.”

The realm of the everyday – or, more accurately, one day – is where Whishaw finds himself as he reunites with director Sachs, following caustic 2023 love triangle Passages. In 1974, as journalist Linda Rosenkrantz set out to document a day in the life of her artistic milieu, she tasked Hujar with writing down his activities over a 24-hour period, before inviting him to her apartment to recount them, on record and in granular specificity, the following day. The book she had in mind that would collate these stories never materialised; however, in 2021, the transcript of her conversation with Hujar was published by Magic Hour Press, 34 years on from his death from AIDS-related pneumonia, aged 53. Sachs’s adaptation sees that conversation reenacted verbatim in a two-hander between Whishaw and BAFTA winner Rebecca Hall (The Town, The Prestige) that only leaves the confines of Rosenkrantz’s apartment for a roof-terrace cigarette.

While technically a duet, the feature swells with the reference to supporting characters in Hujar’s countercultural Big Apple existence. His day features a New York Times shoot with poet Allen Ginsberg, at which he discusses his next subject: author William S Burroughs. He later ponders whether Fran Lebowitz would pen an introduction to his upcoming monograph, although the greater star power – at the time – of Susan Sontag enchants him more. “I often have a feeling that, in my day, nothing much happens,” he admits to Rosenkrantz – perhaps a symptom of the fact that the magnitude of Hujar’s impact as a lensman was only fully acknowledged after his death.

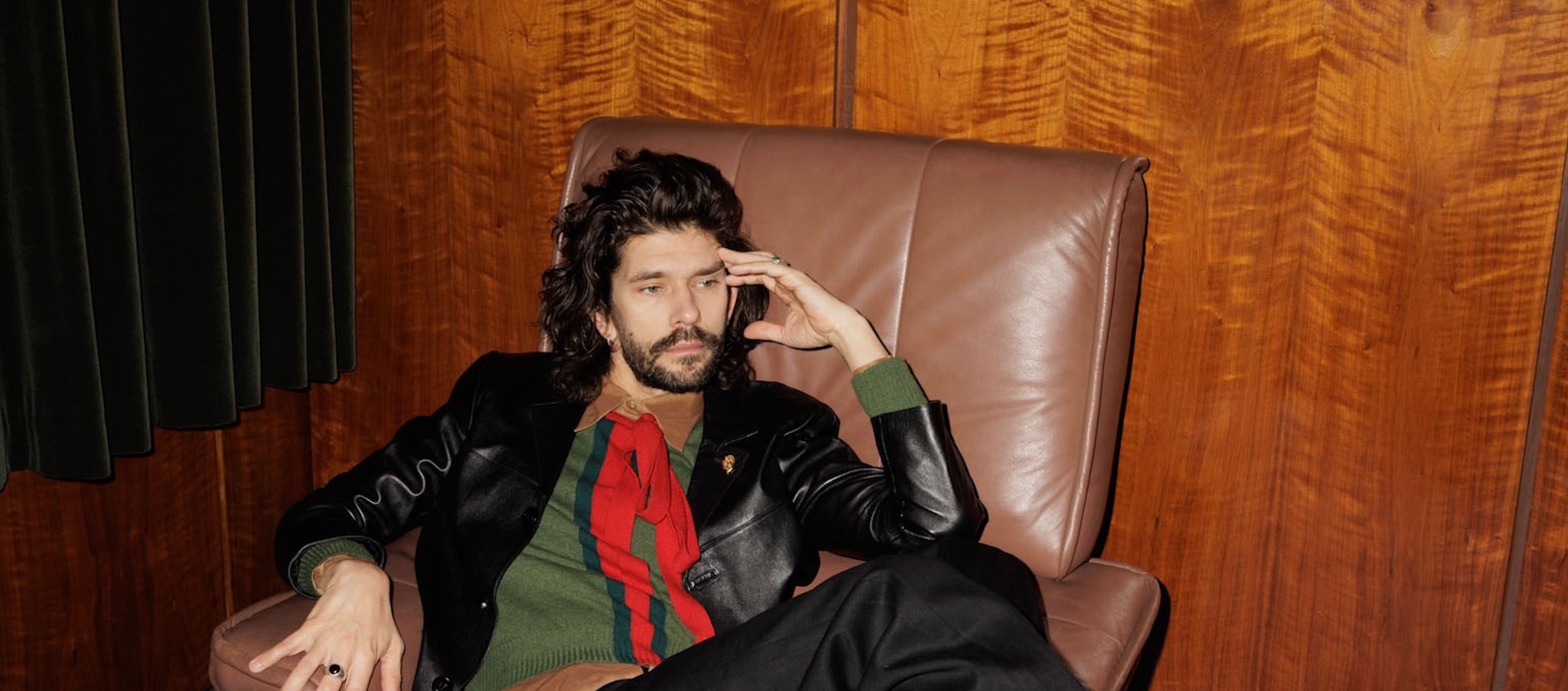

Full look FERRAGAMO, ring TALENT'S OWN

There’s less risk of Whishaw’s career contributions flying under the radar within his lifetime, although he’s unlikely to toast himself. Thankfully, Balogun is on hand for that. “Maybe, I’ll just start with some praise,” he tells Whishaw as they settle in. From Bond, a BAFTA, Emmy and Golden Globe-winning role in Russell T Davies’s A Very English Scandal, state-of-the-NHS drama This Is Going To Hurt and Yorgos Lanthimos black-comedy The Lobster, it’s when you attempt to recall a Whishaw exploit that you’re confronted with the wealth and breadth of them across stage and screen. And who could forget the masterclass in voice acting that is his lead turn in the critic and fan-beloved Paddington?

Balogun’s love of Whishaw’s work is reciprocated, however. Whishaw’s currently in the thrall of the actor, writer and climate activist’s appearance as merciless killer Amos, opposite Emma Thompson, in Apple TV+’s Down Cemetery Road. The last episode releases that evening: “I mean this as the biggest compliment, I really need someone to kill you,” Whishaw laughs, “because you are so evil and frightening.” However, Balogun’s changemaking power offscreen inspires optimism rather than fear, not least with Green Rider, the initiative he co-founded, which is proving a lifeline in the TV and film industry’s adoption of sustainable production practices.

Today, however, Balogun’s attention is on his subject. And Whishaw could prove a tough nut to crack. His masterstroke is, after all, his ability to surprise. “I really don’t like it in life or in acting when someone goes, ‘Oh, I know what you’re all about,’” he tells Balogun. “I hate being defined.”

Ben Whishaw: Hi Fehinti. How are you?

Fehinti Balogun: I’m alright, how are you?

BW: I’m okay, my love. Are you at home?

FB: I am at home. Long time no see. We’re due a big gossip, I think.

BW: Sorry, I didn’t make your birthday. How old did you turn?

FB: 31!

BW: How does that feel?

FB: Absolutely fine. Thirties are pretty good. You’ve found your people. I think the thing I’m proud of is that everyone who meets my other friends goes, ‘God, your friends are really nice.’

BW: Yeah, that’s always a lovely feeling. Forties is really strange.

FB: Why?

BW: Sickness and encroaching death.

FB: [Laughs]

BW: Not of yourself necessarily, although who knows? But of people you love. That can really come to anyone at any time. But it becomes more prevalent. But there are lots of really wonderful things about being in your forties.

FB: I’ve got loads of questions for you. I love homework, so I’ve done it. Ben – you’re so good at acting. It’s like palpably infuriating how good your acting is.

BW: You’re pretty good yourself.

FB: I’m fucking excellent [laughs].

BW: You are incredible. We’ll get to that, too.

FB: But I think one of the things that I like, and I think it’s one of the things that we – your friends, your colleagues, we who have worked with you – find really fascinating about you is that it’s always the bit between that you fill with this life. It’s always the bit between the words or the bit behind or in front of the words. It’s a hard thing to do. With the film itself, it’s a portrait of a day in a person’s life. How hard [was it] not trying to be interesting? I know I would personally be like, ‘Okay, and here’s where I put the razzmattas in.’ ‘And I’ll do a little something here…’

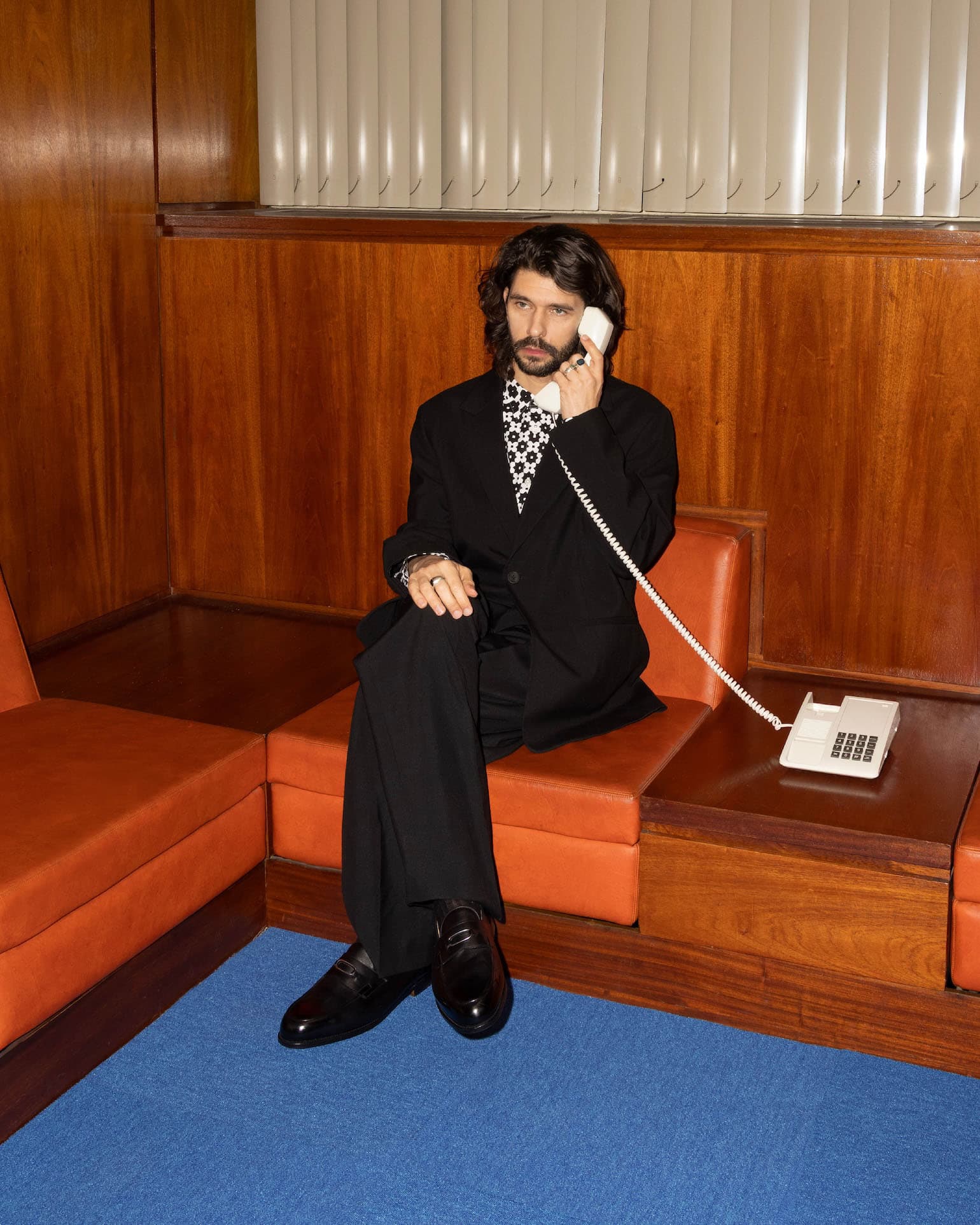

Blazer SOLID HOMME, Shirt COMME DES GARÇONS HOMME PLUS, Trousers FERRAGAMO, Loafers JOHN LOBB

BW: Basically, none of us – including Ira Sachs, our director – knew what this project was going to be. We just saw it like an art project. There was nothing defined about what it would ultimately wind up being. So that changes how you approach something, because there’s no definite audience. All that was concerning me was, ‘How do we realise as fully as possible what this peculiar thing is?’ And when I thought about that, I knew that we couldn’t do the thing that you just described, of being fearful that it was not interesting. You had to just go – ‘This may be not interesting at all. I mustn’t try and dress it up as anything.’ It was more like, ‘I just have to try to sink into this.’ I sometimes get very bored by very dramatic things. So, for me, this was kind of heaven. It’s like when you just watch someone lost in thought at a bus stop or a café, and it’s like no one is there. They’re kind of magnetic. It was an opportunity to explore something like that.

FB: I mean, every play I’ve seen you in, there are these little mundanities and clues.

BW: It’s something maybe that some directors or writers or people who run big studios don’t know so much about or aren’t so interested in. And also it can be, as you say, epic and very dramatic. I think there’s story in everything, and I really just like it when the canvas of a piece allows the eating of a sandwich to be that. Having said this, I am addicted to Down Cemetery Road, which is full of action. But I think what the central four of you do so brilliantly is grounded in character. I’m always just so interested in people and behaviour. I know it sounds like an obvious thing to say.

FB: It is the craft of the thing. You do the audition, you learn the lines, you get into the character. And then there’s what [the role] fucking feels like on your skin. What breathing the air feels like. All the stuff you learn at drama school, put away, never think you’re gonna use, then all of a sudden, you’re like, ‘Oh yeah, really? That’s how…’ With Cemetery, Amos always walks with his eyes open. He very rarely blinks. And [he] always [walks] in straight lines. And that was just like, ‘Yeah, because he’s fucking weird.’

BW: It’s true. You do magnificently the thing of being profoundly frightening without trying to be frightening. Again, I think that’s why you do the part so immaculately because, in life, that is what those people are like. It’s not because they are being threatening necessarily in some overt way, but you just get a feeling. You just go, ‘Oh, there’s something off about that person.’ I actually have wondered where that part came from in you. It’s a big thing because he’s a psychopath, probably, isn’t he?

FB: Yeah, he’s absolutely a psychopath.

BW: But [your character is] very intensely and interestingly moved about [his] brother’s death. I thought that was such another wonderful, human detail.

FB: Contradictions.

BW: Yeah.

FB: The best actors I know are very, very kind. And I think there’s something about that kindness that makes you available to that psychopathy. Because you know what it is to not have it. You play an assassin on Black Doves. Is that similar?

Full look DIOR

BW: Yeah, definitely. Well, I don’t think that they’re necessarily psychopaths… I sort of regret using that word, because I gather that not as many people are psychopaths as we might think. But perhaps the truth is that many people have elements of psychopathy. It’s to do with a lack of empathy. We all, whether we like it or not, sometimes lack empathy. And we all sometimes detach ourselves from what’s really happening in order to protect ourselves and survive. I do that all the time. And it’s only the same thing several degrees dialled up that’s true about a character like the Black Doves character, Sam. So you find a way in yourself. It’s somehow your own self you’re always using, which is why it’s interesting and why, if we’re lucky, you can keep [acting] for your whole life and get better at it.

FB: Yeah. And with [Peter], obviously, you’re playing an iconic figure in history. Did you get into photography? Have you been into photography?

BW: It’s an interest and hobby that I go in and out of doing. I discovered who Peter Hujar was because I started to take photos. I started to become interested in film photography. So [the film] just happened to cross over with an interest of mine that already existed. When I got to New York to make it, Ira sent me to a dark room to learn how to work in a darkroom, because I’d never done that. And Peter talks at some length about the darkroom and the whole process of producing a photo. So I’ve always loved images, image making, paintings and photographs. I nearly went down that route. And some part of me is still very curious about that and wants to explore it more. I think it’s a good thing for an actor because acting is so ephemeral and so ungraspable, but there’s something so wonderful about being able to make an image and capture something. You are a painter yourself, so you have the same thing. Do you find that?

FB: Yeah, I really do. A lot of the art is trying to get a very specific feeling in front of you. Almost like writing a poem and trying to convey something textural and deep. What’s that quote that’s like, ‘Those that are sensitive… their job is to feel the world and report back to everyone how it really is.’ I remember thinking about it the other day, because I was speaking to my therapist about anxiety. And she was like, ‘You know, it comes from you caring. You are affected by the world, which is why you want to affect it.’ This is maybe too much of a share for a magazine, but sometimes, especially when I was younger, I would write diary entries to be read. They were written in a way that if someone were to find them, they’d be like, ‘Oh fucking hell, this is good. And then what happened?’

BW: That’s really funny.

FB: I think there’s something [with art], where it’s like, ‘I need this to exit me so it is observed by someone else.’ I know you said earlier that you didn’t really know what the project was going to be, so you didn’t have to think about that. But, paying an homage to quite a figure in history, at a very specific time in history, was making that piece of art about it being seen and received?

BW: Well, I think it’s a strange balancing act of both things because obviously you don’t just do it for yourself – that would be some weird solipsistic thing that just looped in on itself and went nowhere. It is ultimately about wanting to communicate something with people and share something. But, in the making of it, I think you do have to sort of forget that. If I’m working in a way that feels truly exciting to me, I’m just living it for real. I’ve always felt like acting, for me, grew out of playing as a child and just being completely immersed in other worlds. And, for some reason, I decided never to stop doing that. So I think I’m always trying to get back to that feeling that I had of being completely lost in something. Of course, it’s not only that. You have craft, and you are making a living and all the mundane things. But there’s some little kernel of wanting to really live something.

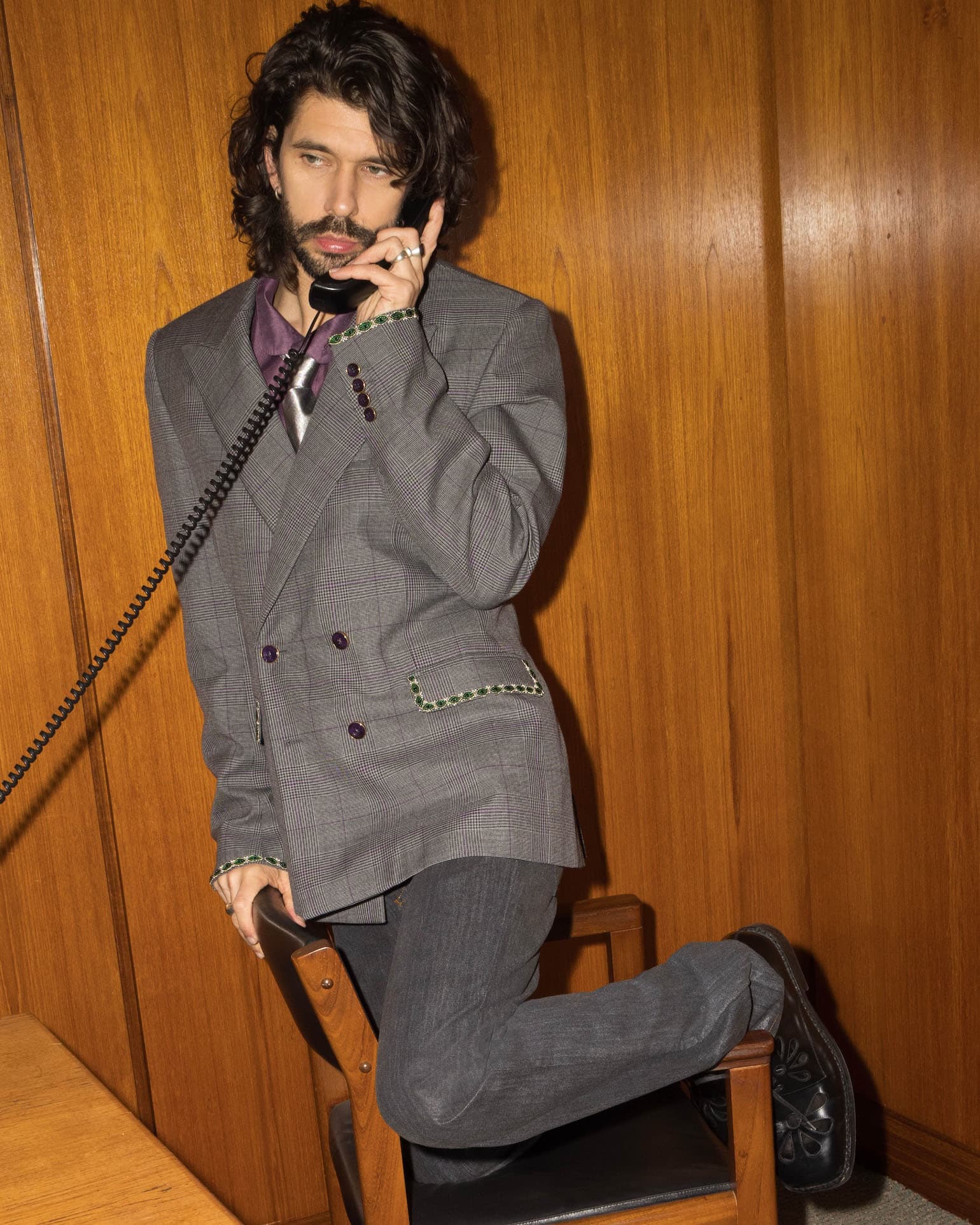

Blazer and tie LOUIS VUITTON, shirt ISSEY MIYAKE, trousers BURBERRY, shoes SIMONE ROCHA

FB: I used to – for longer than I will say publicly – dress up in robes. As soon as I got home from school, that would be my Roman toga and I would have my staff.

BW: Amazing.

FB: That’s where I learned my Shakespeare voice. In my living room.

BW: I think that every actor has that somewhere, going on.

FB: There’s something in the playfulness. In the world of adulting, it feels like everything is very serious, but ingenuity, creativity, solutions that solve huge problems – they come from playfulness, from joy and creativity.

BW: A hundred per cent. And also, it doesn’t have to be one thing and not another. It can be serious and playful. Children are both. At least I was. The game is only fun because it’s taken seriously. If you break the game, it doesn’t make sense.

FB: Absolutely. Peter Hujar’s Day itself is like a snapshot in history. A snapshot where it felt, maybe I’m glorifying it, but the artistic effect on society was more directly impactful and easier to access and create. It’s this time where your picture begins a conversation. The culture of queerness is changing how people are allowed to live their lives. Whereas now there are so many different barriers to making accessible work. Or the way that you can make that work is so altered by those bodies that it’s not the work that you wanted to make. With the time that we’re looking at, it’s like, ‘You had an idea, you had the people, you made the work, and the rawness of it was the art itself.’

BW: I totally agree.

FB: So I think my question to you is, how important do you think art is now in order to create change?

BW: I guess that’s such a big question, and in a way I feel a bit unqualified to really answer it. I guess what I would say I feel is that people can be changed by all sorts of things, in all sorts of ways, and they may not always be massive, but they may be massive. They may be like, ‘I’m going to support this cause.’ ‘I’m going to speak out about that.’ But it can be something internal. I think all of that’s good. Something really changed me the other day, and I’m trying to remember what it was. Something made me think about my mother, and I thought, ‘I have to be more something towards my mother after watching this.’ My point is that I think it happens continually. And as people who make things, you don’t know how it’s going to affect people.

But what do you think, Fehinti? I guess the reason I feel a bit phoney talking about it is because I know that you really do do a lot. You are an activist, so you have a public voice that’s really changing things. And I admire that very much. I don’t have the kind of personality, at least at the moment, to face the public like that. But you may not feel that way either. You may have just wound up doing it through circumstance.

FB: It’s so interesting because I think we work in such a public-facing industry that’s not just about our work. Like we do our work and then we kind of [leave] it alone, and then people intuit, infer and create narratives just around that, let alone us literally going, ‘Hi, I’m Fehinti Balogun, and this is something I believe.’ So there’s that. But Ben, I think you’re doing yourself a disjustice with how you view your validity to talk onto art and change. I think immediately about the integrity of the roles you pick. I think about the LGBT representation you bring into it. From Black Doves to this to, what’s that BBC spy series you did? London Spy. The representation of the work that you choose still, to this day, affects the culture and conversation around LGBTQIA+ things. When we talk about culture and change and choice, I think you are a huge voice in that space.

Full look PRADA

BW: Oh, that’s nice. That’s very nice feedback. Thank you.

FB: I think it’s very much true, and I think that that informs what is commissioned and what is written – what people feel inspired to write. We live in a time and age where there is this rise of very old rhetoric and philistine beliefs that are pushing back the Overton Window of what society deems we’re gonna talk about. So I think that in itself has a huge cultural impact. But being an imperfect person doing the best that you can is so much better than this idea that we have to be perfect and always well-informed.

BW: I know exactly what you’re saying. I agree.

FB: And Ben, also, you were one of the first people I talked to about Green Rider. And you were so supportive.

BW: Yeah, I mean, I’m grateful you spoke to me. And that’s really had an impact on the industry.

FB: Part of the campaign is that you get people who have been in this business for a long time to talk about this thing, and things just get done. Like Charity Wakefield and Bella Ramsey, they’ve engaged with us, and when they get signed onto a project, literally all it takes is, ‘Hi, I’m interested in sustainability.’ ‘I’m interested in this thing…’ ‘Here’s my Green Rider.’ And because we’re connected to the producers on the other side, they then call us and go, ‘Oh my God, this has changed the entire game.’ Because, before that person gave them a call and said, ‘I’m interested in this,’ it was like, ‘Oh, we might have a sustainability person, maybe.’ After the call, someone gets hired, and the whole department is there.

BW: Amazing, amazing, amazing.

FB: Number one, number two, number three on the call sheet is like, ‘This is something I’m interested in,’ the cultural impact of that engagement is fucking huge. Gangs of London reduced 80% of its emissions by changing to HVO fuel, because Sopé [Dìrísù] was interested in having those conversations.

And also, one thing I really want to ask is… your kindness is something I have really internalised. But the culture of our industry is not based on kindness. What is a cultural thing within our industry that you’d love to see changed?

BW: Well, I’m going to just go immediately with what comes to my mind because of conversations I’ve had. In a sense, I’m not the right person to talk about this, but basically, I still think we’re very far from where we need to be in terms of diversity. It’s still too one thing, which is white. The thing I feel that needs to change is who’s being cast, who’s telling stories, and who’s making the decisions about who’s cast. I mean, I don’t need to tell you all this stuff, but I feel also like I can’t be silent about it. And I just feel like aside from everything else, we’re just missing out on richness of stories and storytelling and creativity. And I find it doubly galling after 2020 and Black Lives Matter, when things seemed to be brought to the top of the pile of things that needed attention. And it’s just been relegated to something else again. And I think it’s time to bring it right back up to the top of the agenda to discuss, especially with everything that’s happening in this country at the moment.

FB: I could not agree with you more. And it’s interesting as well because so much of what is in racism and xenophobia is a lack of knowledge. It’s like, ‘Somebody somewhere told you that other means danger. And because you do not know other – you do not know someone who looks like that – then they must be a bad thing.’ And so much of The Kumars, The Real McCoy, Desmond, all of these beautiful cultural windows, change completely how people are viewed and understood. You stop labelling someone as other, and you start to see them as human.

BW: I guess it goes back to the ‘How does work change things?’ discussion and, in that sense, it’s enormously important. But it’s very hard to change people.

FB: Which people?

BW: Whoever is deciding, ‘We will tell this story, but not this one.’ ‘We will cast that person, but we’re not interested in this.’ Whoever those people are, they need to do something – or go. We’re just going through a very conservative phase right now. It will shift again, but we have to keep riding it through, and keep pushing for, as you said, more humanity and not so much othering. More kindness.

Full look DIOR

FB: It does exist. I think sometimes it’s like it isn’t there. But I’m like, ‘Those stories are there. They just need the funding.’ I think there’s something to be said about the wealth of work in this country that we could make. Life-changing, beautiful, culture-creating stories.

BW: I know, and it’s frustrating that it’s not being utilised. I haven’t figured out precisely how yet, but I really want to do more. I would like to use whatever presence I have to do more in that regard.

FB: Also, just really quickly – no rehearsal?

BW: Yes, you did ask me that. I actually love it.

FB: Really?!

BW: Yeah, I love it. But you have to be working with someone like Ira Sachs, who has chosen to do that for a very specific reason and is holding you and supporting you through it. If there’s just no rehearsal because there’s no time and no one cares, and no one’s paying any attention, that’s a very different thing. But if the reason is to capture something that’s very alive and very in the moment… I love those qualities in performance.

FB: I think sometimes – especially for people who haven’t done the job for very long – unrehearsed can be conflated with underprepared. Those two things aren’t the same. Or is it something in the underpreparedness that brings it to life?

BW: I think you’re quite right to say that. I think it’s being very prepared, but in a specific way. It’s absolutely being prepared. It’s like a director who I worked with when I was very young would say to me, ‘Drop the plan.’ Drop the thing that you’ve practised in front of the bedroom mirror or in your bedroom, because, particularly as a young actor, you have to plan. You have to prepare. But when it comes to the filming, you have to be wide open, or try to be. And in a way… be completely in the unknown. It’s very hard, I don’t always manage it, but it’s my aim always. So yeah, you’re right, it’s not about being lazy.

FB: What else did I write on my little pad? I think one thing that I would like to ask you, because I’m curious… you’ve got a really fucking wide portfolio of work. It could just be Bond, one, two, three, big Hollywood thing, one, two, three, four, couple series, three, four, out for a couple years, maybe come back for another Hollywood thing. But there seems to be a really deliberate choice to do things that are fucking interesting. And that are, as you said, close to those mundane but operatically normal moments in life. Why have such a varied career? And is there a risk in doing that?

BW: Everything in me is always trying to keep everything very dynamic, mobile and changing. So once you do something, you want to do something that’s very different.

You’ve got to get fresh air in or change it all up. And I’m feeling it now, actually. I’ve got to find the next thing that’s going to really terrify me, and really challenge me and push me someplace new. And so that is all I’ve really tried to do. I don’t always manage to do it as much as I would like, but it’s always on my mind. And also, it’s just more fun to be very various and unpredictable.

FB: I think I’ve asked you all of my questions. I think the last thing that I will say is a quote from Rebecca Hall. It says, ‘Ben Whishaw is touched with a kind of magic.’

BW: Oh well, so is she. She’s absolutely magical. Look, that’s a wonderful thing to hear, and I’m very touched. But as I get older, I really, truly, absolutely believe that what’s magic is what happens between actors. [The way] that we bring things out of one another. No one is acting in a vacuum, and actually, the true joy is the thing you share with each other. Really, you’re only as good as the person you’re opposite and how present everyone is willing to be.

FB: Yeah, I think it is that. It is being open. It’s exactly what you said about when you play, and you’re in your living room, with the cape. You’re not thinking about when mum’s going to get home. You’re perfectly, perfectly present.

BW: The best things are always the things that you don’t plan, really. The more I get older, the more I’m interested in how everything is an improvisation, and you’re discovering it as you go along, and trusting more.

Photography

Elliott MorganStyling

Jordan LittletonSet Design

Annie AlvinStylist Assistant

Giorgio BonaddioPhotography Assistant

Oliver BrandSpecial Thanks

CLD Communications