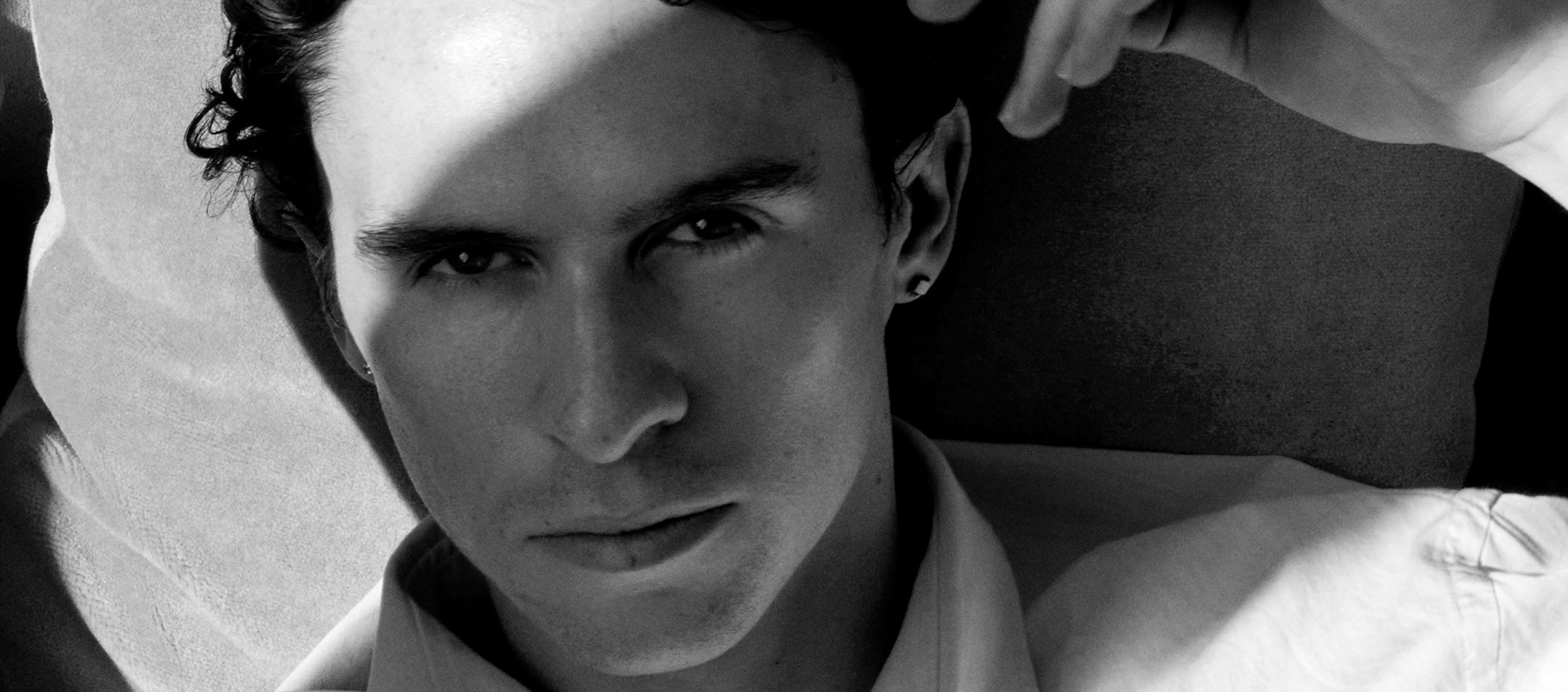

Neither time zones nor career jealousy could stand between the transatlantic friendship of Russell Tovey and Pedro Pascal. It’s a bond that deals in love and schoolboy humour in equal measure. As Tovey covers our Autumn/Winter issue – with a quartet of upcoming releases in 2025’s final quarter (Plainclothes, a Doctor Who spin-off, children’s book and BBC comedy Juice) – he calls on Pascal for a debrief.

Pedro Pascal is envious of Russell Tovey’s career. “In a lot of ways,” he admits. “I’m always telling you [this]. Seeing you at The National Theatre in Angels in America, or in Harold Pinter plays [in the West End]. You don’t know how good you have it!” Tovey’s theatre exploits sit front of mind for Pascal. Still, he’d also have liked a gig like Him & Her – the vérité 2010s BBC Three sitcom, in which the Essex-born actor starred as one half of a 20-something couple who rarely passed the threshold of their East London bedsit. Pascal discovered it while working in the UK and would quote lines to Tovey when the pair first met.

In fairness, Tovey has a CV worthy of coveting. He’s now co-leading Plainclothes, alongside The Hunger Games’ Tom Blyth. Carmen Emmi’s taut, affecting look at the police entrapment of queer men in cruising spots in the ‘90s is being hailed as one of the standout LGBTQIA+ releases of the year. It’s the latest addition to the constellation of genre and intention that is Tovey’s portfolio. Since breaking out in critically-adored grammar school drama The History Boys in 2006, British comedy institution Gavin & Stacey, Andrew Haigh’s 2014 portrait of millennial gay life Looking, and the prophetic near-future dystopia of Russell T Davies’ Years and Years are among the projects to be graced with his protean thespian ways. He’s also co-hosted Talk Art with gallerist Robert Diament since 2018 – a hit podcast, also spawning books – that decodes contemporary art in defiance of industry elitism.

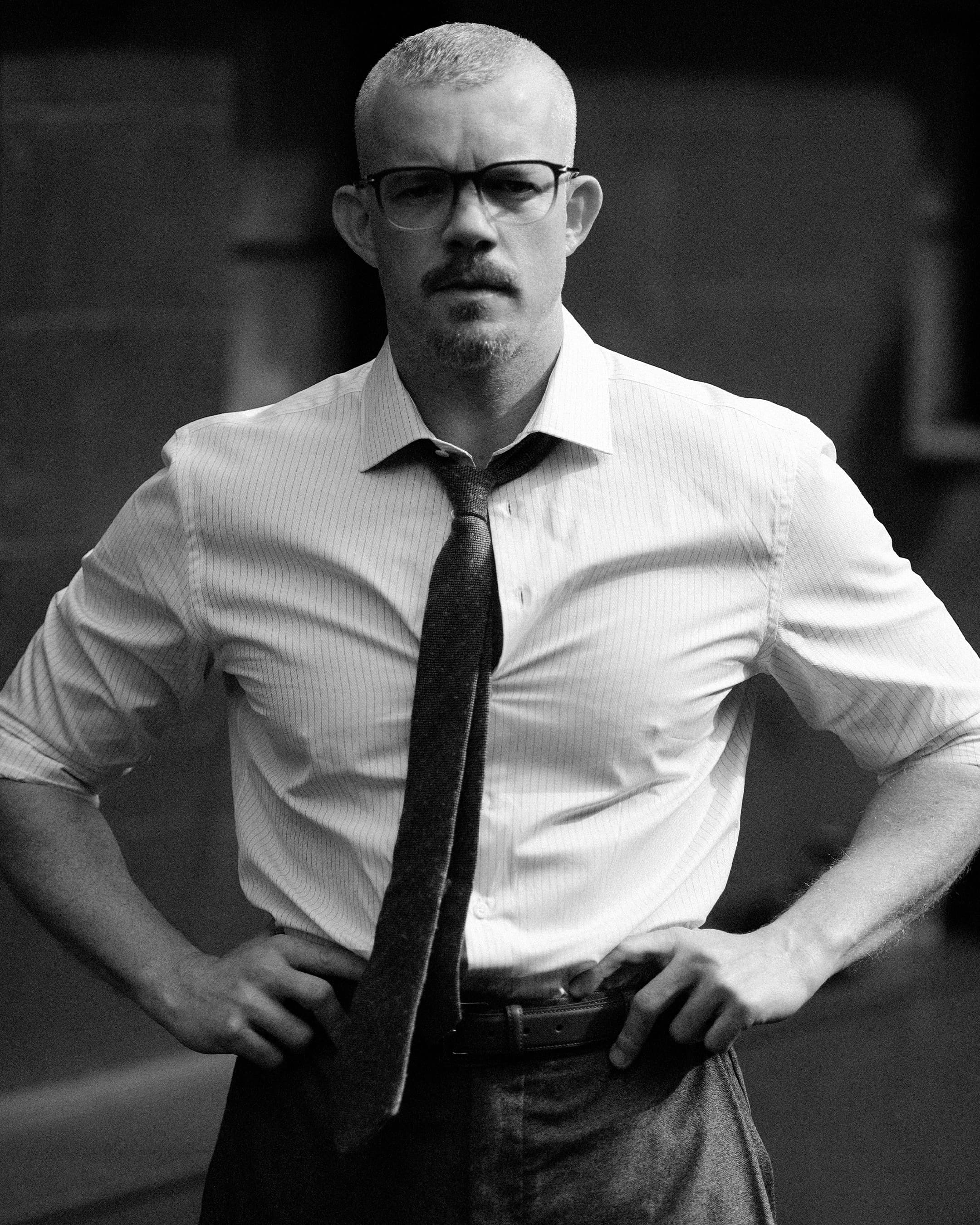

Russell wears shirt THOMAS PINK; tie BRUNELLO CUCINELLI; trousers & belt GIORGIO ARMANI; spectacles MONTBLANC

Envy aside, Pascal’s own professional fortunes are far from faltering. His 2022 international breakthrough in the appointment-viewing The Last of Us has made him one of his generation’s foremost A-listers – complete with SAG and Golden Globe nods, plus successive blockbusters (Gladiator II, The Fantastic Four: First Steps). But, today, affable as ever, he’s simply being candid with his old pal. And he can be – this transatlantic bromance is almost 10 years strong, after they connected when Pascal was on UK soil for work in 2016.

Last year, the pair were in touch every week when Pascal’s shooting commitments brought him across the pond once again. There are some discrepancies in Tovey’s memory of their correspondence, however. “[Were] we?” he laughs. Tovey was in Cardiff filming upcoming Doctor Who spin-off The War Between the Land and the Sea. “Are you stupid?” Pascal quips. “I had tabs on your schedule and I’d be like, ‘Are you going to come [to London] for this long weekend or not?’ But, you know what they say, ‘People with bad memories are happy people.’”

“Ignorance is bliss!” Tovey concedes. A level of ribbing not out of place at The History Boys’ Cutlers’ Grammar School would appear to be the cornerstone of this attachment. They swap out each other’s names for “Stupid” upon address. Pascal quickly takes Tovey to task on his askew pronunciation of the Plainclothes filming location, Syracuse, before they piece together a drag name from it. They conclude that being “vers” is the “best way to be” less than 15 minutes into their call. But as any sturdy male friendship requires, they can flit from sarcasm to the serious stuff in seconds. Tovey’s frank on the shame – a tentpole theme of Plainclothes – ingrained in gay men of his generation. So too is Pascal on how the film opened his eyes to the persecution the community faced just a stone’s throw from his “bubble” socially progressive existence as a ‘90s NYC drama student.

Russell wears shirt & trousers DUNHILL

And, perhaps, best of all, they’re forthcoming with praise – envy or not – for each other’s talents. Pascal thinks Tovey looks “great and very handsome” in The War Between the Land and the Sea trailer. “You always deliver, you little bitch,” he beams of one of Plainclothes’ perfectly-pitched moments. And Tovey’s also on hand to walk him through the unfamiliar lark that is interviewing – playing his own publicist when he has to jog Pascal’s memory on the many upcoming projects that figure in his horizon.

But Pascal is, in fact, well researched. He’s just watched Plainclothes as an accompaniment to his morning coffee in LA. Now he’s snacking on some almonds. Tovey’s at a different end of his day in London, perched on his bed with French bulldog Rocky reclining at the bottom.

Russell Tovey: Talk to me, Pedj.

Pedro Pascal: Where are you, Stupid? Are you at home?

RT: Yeah.

PP: Why are you in bed?

RT: It’s cosy and Rocky wanted to hang out. What are you eating?

PP: Almonds. Yeah, anyway, I just finished Plainclothes, so it’s fresh.

RT: Did you watch it this morning? First thing?

PP: Yeah. It was a cosy thing to do with my coffee, not that it’s a cosy movie, although it is quite in the end. Where did you shoot that?

RT: Syracuse.

PP: [The director] Carmen – where’s he from?

RT: Syracuse. So all of his family were like helping out.

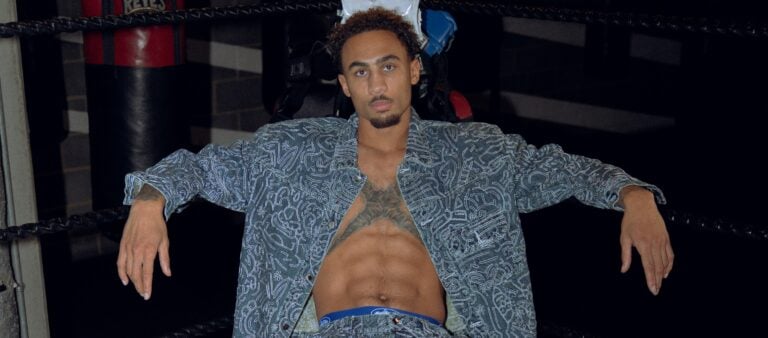

Russell wears jacket LANVIN; trousers BERLUTI; shirt EDWARD SEXTON; tie STYLIST'S OWN

PP: Oh, wow. It’s so interesting, because it’s a period film, amongst many other things, and [in 1997, when the film was set], I was in my final year of college. And after two really rough years of an adjustment period, having moved there to go to school, by 97, I was sort of hitting my groove, or so I thought. Anyway, I was watching this movie, like, ‘Where is this? Is this New York State? This is clearly the East Coast.’ There’s footage in it that makes you feel like it’s 1960s London, where gay men were being hunted. And men were being hunted in this period, even within Manhattan, I suppose. But, in my little bubble, it was just so horrible to be homophobic or bigoted, and all of these were such clear injustices in such an obvious way, and yet it was still completely going on. And I don’t know. I’ve not asked you a single fucking question…

RT: No, I like it, it’s an interesting observation.

PP:That period in my life is such an imprint of learning so much and knowing what’s right. And right outside, as close as across the street or in a town right outside of Manhattan, was this scary repression. I mean, it goes on today. You know, it’s kind of a timeless thing. Some things have changed, and some things fucking haven’t.

RT: Yeah, it’s cyclical, isn’t it? Well, this is set in ’97, which is the year [before] George Michael got busted.

PP: And he got busted in the US or in the UK?

RT: Los Angeles.

PP: So ridiculous. So he got targeted. And it is, it’s targeting, because you’re sort of manipulating a taboo number one – a vulnerability. And some good-looking cop flirting with a closeted man or a man just going through their innocent day.

RT: It resonates.

PP: Yeah. And we know you’ve been busted 100 times.

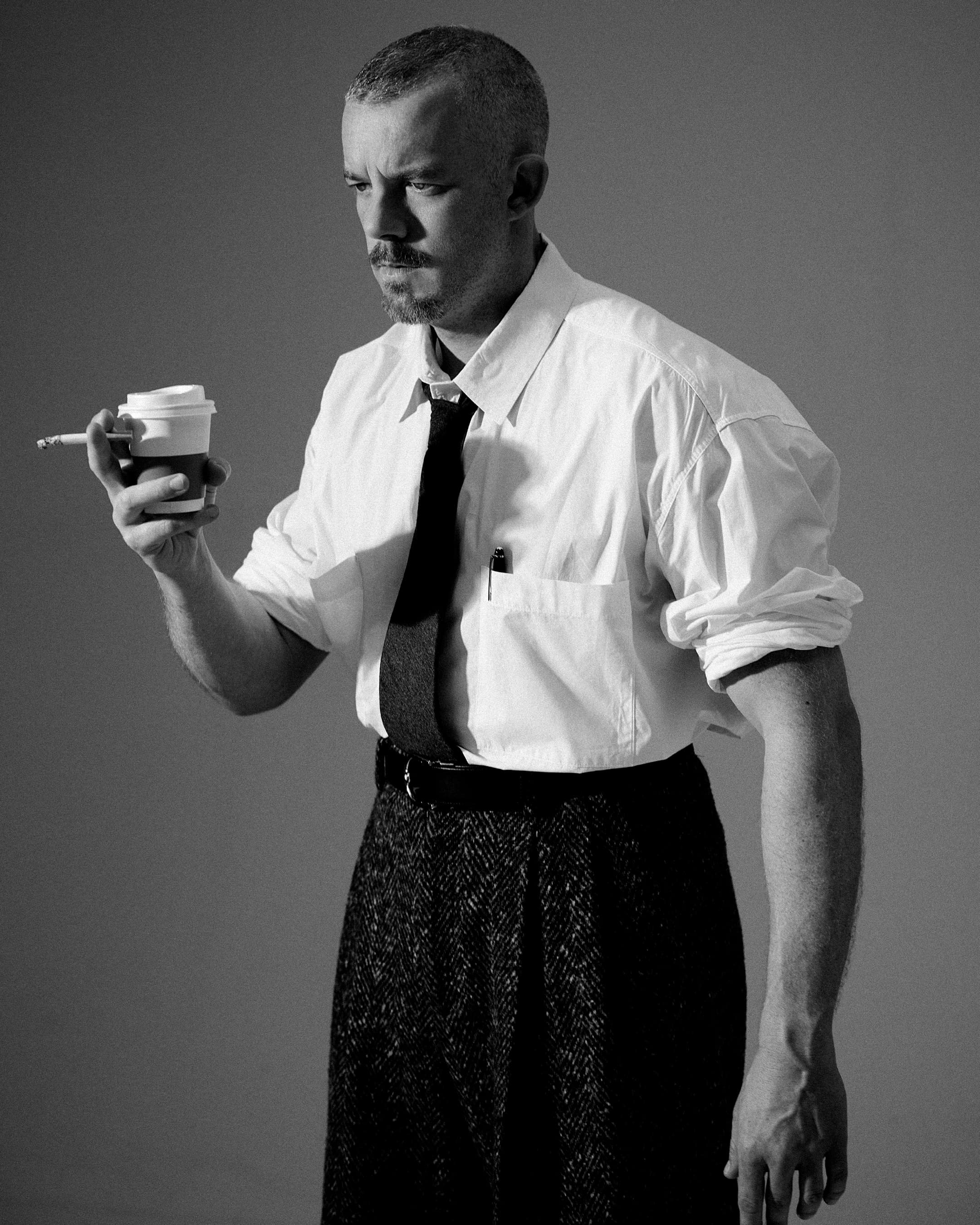

Russell wears shirt FRANKIE SHOP; trousers DOLCE & GABBANA; tie PAUL SMITH; belt & pen MONTBLANC

RT: [Laughs] Yeah, this is a documentary.

PP: ‘Inspired by true events’ was in the talking points! How did this come your way?

RT: It was a conversation with a producer who I made a short film with a couple of years back, called April Kelly. She’s one of the many producers on this. She got the script to me and said they’ve been trying to get it to me. ‘Will you have a read?’ I read it and loved it. And then they said that Tom Blyth was attached, and he’s super cool.

PP: Did you know Tom before working with him?

RT: I didn’t know him, but I didn’t know he was British. He went to Juilliard in New York, and I assumed he was an American actor.

PP: What a traitor. Take that, RADA.

RT: Yeah, exactly. Go to Juilliard! But then Carmen just said, ‘Come on and have a conversation with Tom.’ And I did, and I was like, ‘This guy’s fucking great.’ And we read a bit, and it felt amazing. I was like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’ So I got out to Syracuse two weeks into filming, because, as you know, the film is two [narratives]. You’ve got [Lucas] before we meet, and then you’ve got [Lucas] after we don’t talk anymore, and his life then. And they filmed all [the latter] first. So I turned up and they were already two weeks in. But it was a beautiful job. And I felt very romantic about Syracuse. I remember I dated someone from Syracuse, and it always sounded so like a nursery rhyme, ‘Sir-uh-coos’. It’s something about the word…

PP: Well, it’s pronounced ’Sir-uh-kyoos’, so your nursery rhyme is already off [laughs]. If you’re gonna romanticise it, at least romanticise it correctly.

RT: Syra-cute.

PP: Syra-cutie…

RT: That’s my drag name. Anyway, I was there and I fucking loved it. And it was one of those – I’m sure you’ve done many as well – where you have a wonderful time but you think, ‘Nobody’s going to see this. It’s never going to see the light of day, but great memory.’ And then the film is now having this thing. It won an award at Sundance. It got proper distribution, it’s so exciting.

PP: There’s something so nostalgic about the movie, too, thinking about what independent queer cinema was in the ‘90s as well. It feels like it isn’t existing [today] with the voice it had in the ‘90s. It was a really, really great chapter of independent queer cinema.

RT: What do you remember?

PP: I remember Gregg Araki. I remember Todd Haynes. I remember a movie called Go Fish, High Art, which I think came out in 1997. Jeffrey, which was in the mid-’90s. It’s not enough, clearly, but it felt like a really important period of movies that were being made and multiple a year. And they were celebratory in terms of the queer experience. I love that this is sort of a dark thriller, and even an erotic thriller, really, because something is so heightened in these archetypes. You have a priest, you have a cop, and so there’s all this fantasy there. And then the eroticism of danger, and also just beneath all of that, the grief of shame and the poison of shame and the liberation from it, which is really, really beautiful. So talk about all of that. Even though you’re not very smart.

RT: I like shame as a theme and how we can be highly functioning and full of shame.

PP: How we basically are highly functioning and full of shame…

RT: I mean, yeah, myself as a gay man, I do find that inherently, I have been embedded with shame from a young age – the year I was born, the coming of age, the way the history was, the way that society was built for queer people. I just didn’t feel like I was safe, and I think I had inherent shame. And I think you always have that. I feel like my character, Andrew, is filled with shame, but he’s highly functioning, and he knows how to survive. He knows what he has to do and how he wants to be, and he knows how he can’t be, and he’s accepting of that, but he does what he has to do. And he meets Lucas, and it’s meant to just be a hookup, but there are emotions involved, and for him, emotions are dangerous. They are not things that he wants to have to think about. It’s just functional. ‘Do that, go back to my wife and kids, go back to my community, do my thing, go back to the congregation, and then go back out again when I get the urge. And then suppress the urge.’ And then he meets Lucas, and it completely flips him around – literally, metaphorically and physically.

PP: He’s vers…

RT: Yeah. And so is Lucas. It’s the best way to be. Vers is the best.

PP: Lucas discovers that he’s vers.

RT: But the whole thing with Lucas is… because of this period in history, I wanted Andrew to be a positive figure. He knows it’s [Lucas’s] first [gay sexual] experience, and he continues with it. I didn’t want it to be a malevolent, dark energy that gives him his first experience.

PP: Are those conversations that you had with Carmen?

RT: Yeah. And I said, ‘I want condoms to be visible. I want Andrew to make sure that he’s kind to him. He’s very clear. He’s very boundaried, and he’s like, ‘This is what happens…’ So it’s more of a shock to him when Lucas overrides that. But I wanted Andrew to be someone that when Lucas walks away from it, he can be like, ‘I practised safe sex. He was very clear with me. He said, “This is the situation…” from the start. “I don’t meet people more than once. This is what I do…”’ I would have liked my first experiences to be with someone like that, if that was the case. It wasn’t the case; I was all over the shop. But that I feel was really important for the period and for that character, and, you know, it’s a power dynamic, where I have all the power. I’m the older man, I’m the more experienced. Then you find out suddenly that he’s a cop, and the power shifts incrementally in a second. And [Andrew’s] like, ‘Oh, fuck. So you were trying to target me in the bathroom?’ It’s all of those conversations. And I love the fact that this film just flips it around like that. And I’d say it is a romantic thriller, because you do care about this couple.

PP: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. It checks all the boxes around thriller. It’s a highly erotic thriller, a highly dramatic thriller, a romantic thriller. It’s full and vers.

RT: What was your favourite bit, Pedj?

Russell wears Jacket, shirt, trousers DUNHILL; tie KINGSMAN

PP: There are a lot of things that I loved. I loved how, in such a small-scale way, there was such a Brokeback element to when they go into a greenhouse, and despite how hidden and forbidden and still secret and dangerous the circumstances were, they’re surrounded by flowers and colour.

RT: Someone said it was like The Wizard of Oz.

PP: It creates a positive portrayal of what [Lusas’s] first experiences of intimacy are. You know what I mean? In spite of the fucking pagers. Pagers, man, what a nostalgic thing, because I was auditioning in New York [in the 90s], and it was all pagers and pay phones. Whenever you had a fucking audition for a bubblegum commercial or something, you got paged. You had to call your manager from a pay phone, carry quarters around with you, and they’d be like, ‘They need you to be on 37th by three o’clock, can you make it?’ Unfortunately, it wasn’t pagers for sex.

RT: Andrew’s pager wasn’t for sex; that was for his wife. She probably does want to have sex as well.

PP: The wife? She may need it.

RT: She’s got needs.

PP: She may need it more than anybody. The poor thing, she’s the only one who’s not getting it. So anyway, I guess that’s my favourite bit. I also loved when he confronts you and you’re so vulnerable and beautiful, and it’s just such a 10 out of 10 scene. Where in shooting was that, in the church? How much had you gotten to know the experience? And what’s this goatee [you’re sporting]?

RT: I’ve done it for a short film where I’ve played a man who’s part of the manosphere, like incel culture.

PP: All right, back to Plainclothes – that scene, you know, when he confronts you and you really are… not broken down, but you’re [showing] fear, because there is love between you and Gus, and its limitations are quite tragic. And you play that really beautifully. And I was just wondering where in your shooting experience that day came?

RT: It was towards the end, I think.

PP: And what was that day like?

RT: You know what? I woke up every single day, and I was excited. That doesn’t happen all the time on jobs. I was keen to get on set. What Carmen created on set was beautiful. Something which I’ve taken on to every project since is that he played music into every scene. So during rehearsals, or if it was a scene where there was a lingering look, he would just play music in, and it would be like emo stuff from the ‘90s or classical music or whatever. It’s an instant hack when you hear music.

PP: Instant. It’s the best. It’s diabolical that people don’t do that more on sets. I mean, I’m always going around with my headphones.

Shirt THOMAS PINK; spectacles MONTBLANC

RT: To actually be able to play a scene where they play music – I took it on to my next job, The War Between the Land and the Sea, this Russell T Davies show. And I said, ‘I really want you to put the speakers on and play music.’ And it was basically the end of Gladiator music. So Hans Zimmer – the original film. We didn’t have your one at that point. And, instantly, I was just like, ‘I’m there. It’s drama, it’s fucking rousing.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, is the crew gonna get pissed off?’ They’d be like, ‘This fucking music.’ And then you look at everyone, and they’re all locked in, because we all love film. So we all buy into that. So Carmen gave me that. Every day on set, I was learning, and he was so open to improv, quietness and pauses and again, so often you get told to, ‘Let’s do one [take] a bit quicker.’ ‘Let’s make sure we get all the lines on this one.’ And there was such a beautiful, loose kind of queer love energy. And me and Tom loved each other, so we were locked in. It was just really fucking beautiful. And it’s such a privilege now that people like it, and it’s getting such a response.

PP: That’s the greatest thing about a more small-scale experience that, ironically, [despite] the budgetary limitations that exist, the creative is so much more free and liberated. And everyone’s there because they really fucking care. Nobody’s there for the paycheque, and it’s such a creatively nurturing and liberating environment to be in. I’m really glad you did it, and you’re wonderful in it as always.

RT: But that’s what Sundance was like. And it was my first time at Sundance, you’ve been before…

PP: I went, but I went so late in my life, and I think it was sort of a different experience. I’m happy you got to go with a movie like this.

RT: It’s just beautiful because there’s a real community of filmmakers and storytellers, and everybody knows what everyone’sdoing, and everyone is upbeat and conscious to connect and learn and educate each other. And it’s because there’s no money. Everybody there is going, ‘We’re doing this because we care about the arts and we want to fucking connect.’ You go, ‘Wow, that’s why it’s so special.’ Because at that level, it’s like people are literally just going, ‘I have to fucking tell stories. I have to do it, even if I’m losing money. I have to put myself out there.’ And that’s beautiful. So this film has been wonderful. Thank you for watching.

PP: You’re welcome. Thank you for forcing me to watch it.

RT: And making you do this interview [laughs].

PP: So now let’s pivot to franchise and go into Doctor Who. All I’ve got to see is the trailer, but it looks so fucking cool. It looks like another really rich, wonderful character.

RT: Well, it’s Disney… What was The Mandalorian? That was Disney, wasn’t it?

PP: Yeah. The Mandalorian premiered with the premiere of Disney+.

RT: Wow, fucking hell. So, yeah, this is like a five-part Doctor Who spin-off by Disney and the BBC. I fucking loved making it. I mean, I have no idea what it’s going to be like. I’ve sat through three days of ADR dubbing, looking at my own face, having to do a breathing track for every episode, where we just watch every single scene, and I’m breathing in and out.And I left there basically having a panic attack, just thinking, ‘What the fuck is this?’ But, again, I love doing that job, and I hope that really connects with people. And the character is an everyman, and I really am drawn to those guys that are flawed or have been overlooked and slipped between the cracks.

PP: I got chills watching the trailer. It looked really good.

RT: I appreciate that.

PP: I don’t know a lot about Doctor Who, but it felt like an elevated, less sort of procedural version of epic, sci-fi television.

RT: It’s in the umbrella of Doctor Who, but it’s very different, I think, from Doctor Who.

PP: Yeah, it looked so. I’ve got to open up the email and see what else the fuck I’m supposed to ask you

RT: You’ve got to talk about Juice, which is a second series of a comedy I do.

PP: I don’t need to talk about Juice!

RT: Something that you always used to say, which always astonished me, and still does, is that when we first started hanging out, you really got into Him & Her. You watched all of Him and Her, and you used to quote bits, and you were really into it. I mean, I love Him & Her, but it always astonished me that you were so enthralled by it, because not many Americans know of it, or have really committed their time to watching the whole thing.

PP: Well, the great thing about streaming is that you get access to so many things that you don’t know about. And there are so many great English comedy series that lots of people don’t know about. There have been the big crossovers, of course, but there’s Peep Show and then Him & Her. It was a BBC show, wasn’t it? But it was streaming on Netflix when we met, when I was shooting Kingsman. And, I mean, it’s a great show. It’s very well written and hilarious and sweet. When it’s not the four [core cast], it’s very much a two-hander. Anyway, I haven’t seen Juice Season 1.

RT: I think you’d like it.

PP: I saw the trailer, and I know I would like it.

RT: It’s written by Mawaan Rizwan, who I saw in Edinburgh in like, 20-fucking-18. And he did a stand-up routine about his life. I met him afterwards, and I went, ‘If you make that into a TV show, I want to play your boyfriend.’ And he was like, ‘Okay.’ And then, literally, a few years later, he sent me a pilot and said it’s been picked up and went, ‘I want you to play my partner in it.’

PP: Oh, wow.

RT: I was like, ‘Great. ’ So I play his partner, who’s a therapist, and his mum is played by his real mum. His brother’s played by his real brother, Nabhaan Rizwan, who’s a superstar. His best friend is played by his real-life best friend. So it’s a really beautiful energy and really kooky and abstract. We’ve now got the second series that comes out soon, and it’s completely flipped on its head what happened in the first series. He pushes that abstract humour even further. I’m really proud of that, and proud of Mawaan and what he’s achieved.

PP: I’m really glad to see it. And what I love is that you’re out there in the world, seeing work that’s new from people we haven’t met yet and then helping make it happen, like, seeing something in Edinburgh, and then now it’s a series. There’s just such an element of hope to know that that’s happening, and that that continues to happen. Do you know what I’m saying?

RT: I do, but I also feel like that’s an energy you possess. You’re endlessly curious and enthusiastic about what we do – new talent, emerging talent, emerging voices. If you can even just DM someone and go, ‘That was fucking great.’ I love that. That encouragement, whatever field it is, from someone who’s already established themselves in a certain position – you have no idea of the impact of that. When I’ve had people DM me who I respect and say, ‘That was great work.’ It feels fucking brilliant. Or when someone you like goes, ‘Oh, I like what you do,’ you just go, ‘Wow, you know who I am.’ So to interact and connect and attach yourself to projects with young, emerging voices, there’s nothing more exciting, is there? I love a new play by a new writer and that freshness. That’s why working with Carmen on Plainclothes was so wonderful, because this is his first film. For him, it’s like, this must be so exciting because he can really curate what he does next. And people want to work with him because of the impact so far. It’s not even been released, but just the reactions from people.

PP: I think you’re right. I think the most important function is being a cheerleader to anybody with a creative voice and a support system in any fucking way that you can in the hope that that individual will continue fighting another day. Or that it could possibly help in a small or big way to put their work out there. It’s kind of the meaning of life, in a way. The testimony of people’s experiences and telling stories. Alright, stupid, is that enough?

RT: I think so. This has been wonderful. I love you, Pedj. Thanks for this.

PP: I love you more. I’ve always loved you more, which is a real shame. I’ve been on Talk Art. I haven’t been asked back…

RT: We’d love to have you back.

PP: Appreciate it. Jeez. You’ve got another book coming out now [Art School (in a Book): A Future Artist’s Guide to Contemporary Art]. It’s a kids book. Tell me about that.

RT: It’s a call to arms. It’s encouraging children’s creativity, whether they want to be artists themselves, or to be allies of art, to be fans of art, to feel like art is for them. I think as we get older, we lose our ability to access creativity, especially when it comes to art. And as kids, we’re so open to it with no embarrassment or no perception of judgment, we just get given a task and we do it. And this is the sort of book that I would have wanted as a kid. That was the reason we started Talk Art. I wanted to create something that I would want to listen to, that gives me an invitation and access into this world that feels very frightening at times, and not set up for someone like me. And that’s why we keep doing these books.

PP: I think that is so well-threaded to what we were saying before. It’s taking cheerleader to another level, and to anyone young, it’s guidance and inspiration to exist in the world as they want to exist.

RT: Correct. I think art is the greatest way to work out how the world is, who we are as humanity. Would you buy the book?

PP: No, you’re going to gift it to me.

RT: I am. Talk Art will gift you that book, I’m sure.

PP: Thank you.

Photography

Jason HetheringtonStyling

Luke DayEditor-in-Chief

Luke DaySenior Editor

Andrew WrightArt Director

Michael MortonProduction Director

Lola RandallJunior Art Director

Natasha LesiakowskaPhotography Assistant

Alfie BungayStyling Assistant

Zac SunmanStyling Assistant

Nicholas SkeensVideography

David J Adams

![Picture of “When We Were Developing Series [2], We Were Very Conscious Of The Live Debate About What It Means To Be British”: Tom Hiddleston On The Night Manager’s 2020s Comeback](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2Fdigsfo-768x338.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_AhPDpVcvBHi6ZdoK89nsTL2Qj1WA)

![Picture of “[The Bridgerton Press Tour] Is Like Being On Some Sort Of Hallucinogenic Drug”: Luke Thompson Is Next In Line](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F01%2FLUKE-THOMPSON-hero-768x339.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_AhPDpVcvBHi6ZdoK89nsTL2Qj1WA)

![Picture of “[Whether Photographing] A Dustman Or The Queen, I Will Try My Best – But, Naturally, The Queen Was A One-Off”: David Montgomery On Capturing Icons](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F12%2FDM-Hero.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_AhPDpVcvBHi6ZdoK89nsTL2Qj1WA)