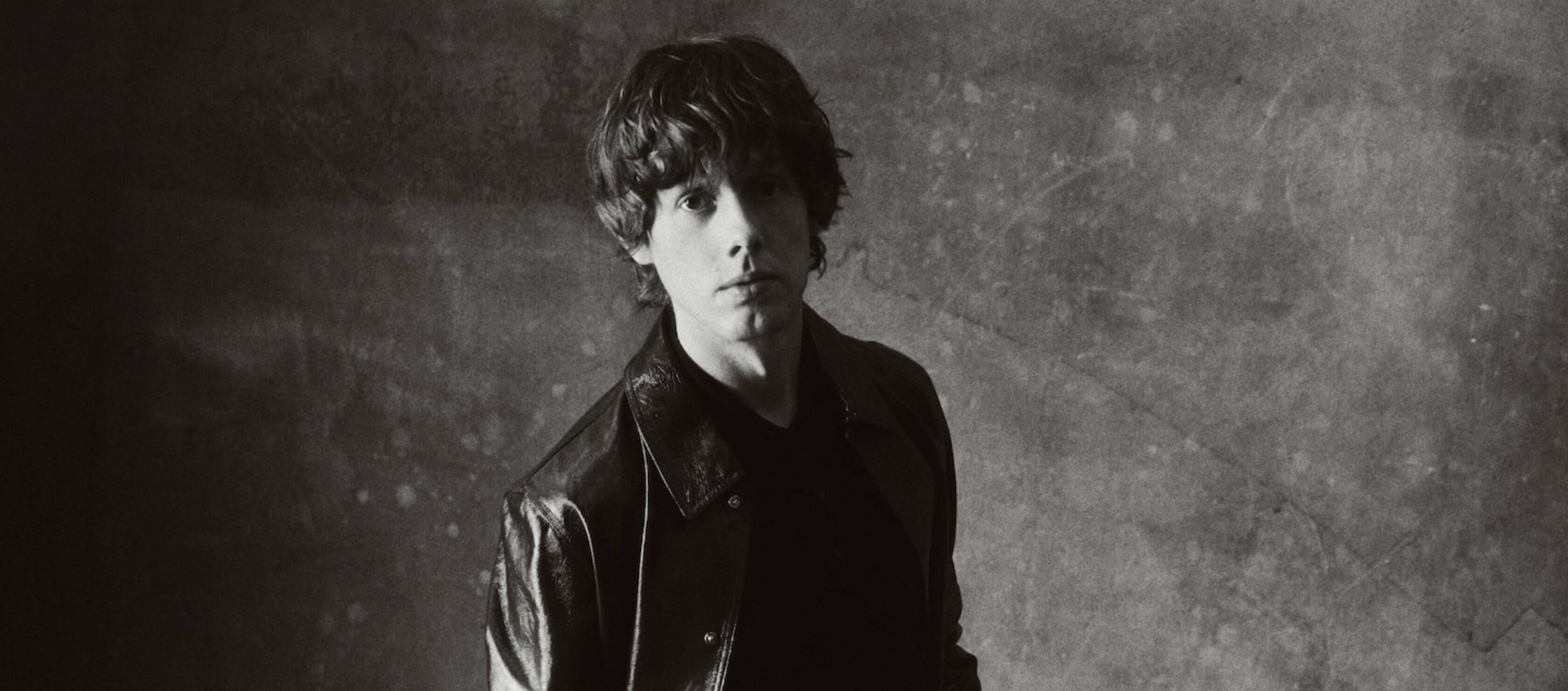

As the son of a triple Oscar-winner, the 27-year-old has a lot to prove in a nepo baby-fatigued world with his new art exhibition (Anemoia) and debut feature film (Anemone). Thankfully, his talents far outweigh his surname.

“I’m definitely slightly shitting myself,” Ronan Day-Lewis quips with a boyish smirk. A duo of significant checkpoints in his two creative passions, filmmaking and art, lie directly ahead when we catch up in the opening week of September. His debut picture, Anemone, will soon appear before audiences at both New York and London’s film festivals before premiering in UK cinemas on 7 November. His largest solo exhibition, Anemoia, will show at Megan Mulrooney Gallery in West Hollywood from 13 September. “There were times when I was making the show that I was like, ‘Why have I done this to myself? Why am I doing these both at the same time?” he reflects. “But I actually now am grateful for it.”

Put yourself in Day-Lewis’s shoes for a moment, and you can understand why he has felt that this enterprising level of polymathic ambition is necessary. His grandfather, Arthur Miller, was perhaps the apexian US playwright of the 20th century. Texts like The Crucible and Death of a Salesman have been mainstays on stages across the Western world for the last 70 years, and are etched in English literature syllabuses to this day. His mother, Rebecca, is an acclaimed painter, writer, actor and director, most recently behind the camera for 2023’s quirky comedy She Came To Me, starring Peter Dinklage and Anne Hathaway. And his father, Daniel, is widely regarded as the greatest actor of his generation, with seminal roles in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, Martin Scorsese‘s Gangs of New York, and Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. He has been retired for the last eight years – until now, returning to co-write and star in his son’s peculiar and understated drama about familial turbulence and the suppression of male emotion, Anemone.

It’s quite the pack of high achievers to live up to – and cynics would argue one hell-of-a-career leg-up. But while the nepotism label will invariably be one that he struggles to shake off, at least in the early parts of his career, once you see his work and understand what makes him tick, it’s clear that Ronan Day-Lewis is more than a product of his family’s fame.

He is a unique, specific filmmaker and a fearless, evocative painter. His work across both of his chosen principal disciplines is dense and serious, but the man himself is lighthearted, amenable and sharp of wit. He calls in from his apartment in Williamsburg, New York, cheery in his natural habitat, having recently returned home from 10 or so months living in Dublin for Anemone’s post-production. There, he drank “a lot of Guinness,” got to know the capital of the country in which he spent six years of his childhood – in east coast town Wicklow, between the ages of seven and 13 – and worked on pieces for his aforementioned art show.

“Anemoia is a concept I came across online,” he explains on the exhibition’s inspiration, shifting his lawless waves away from his eyes. “It’s about nostalgia for a time or a place that you haven’t experienced. That’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot in my work for years, this idea of creating the sense of something that feels oddly familiar to you – almost like it could be your memory as the viewer, but it’s not.”

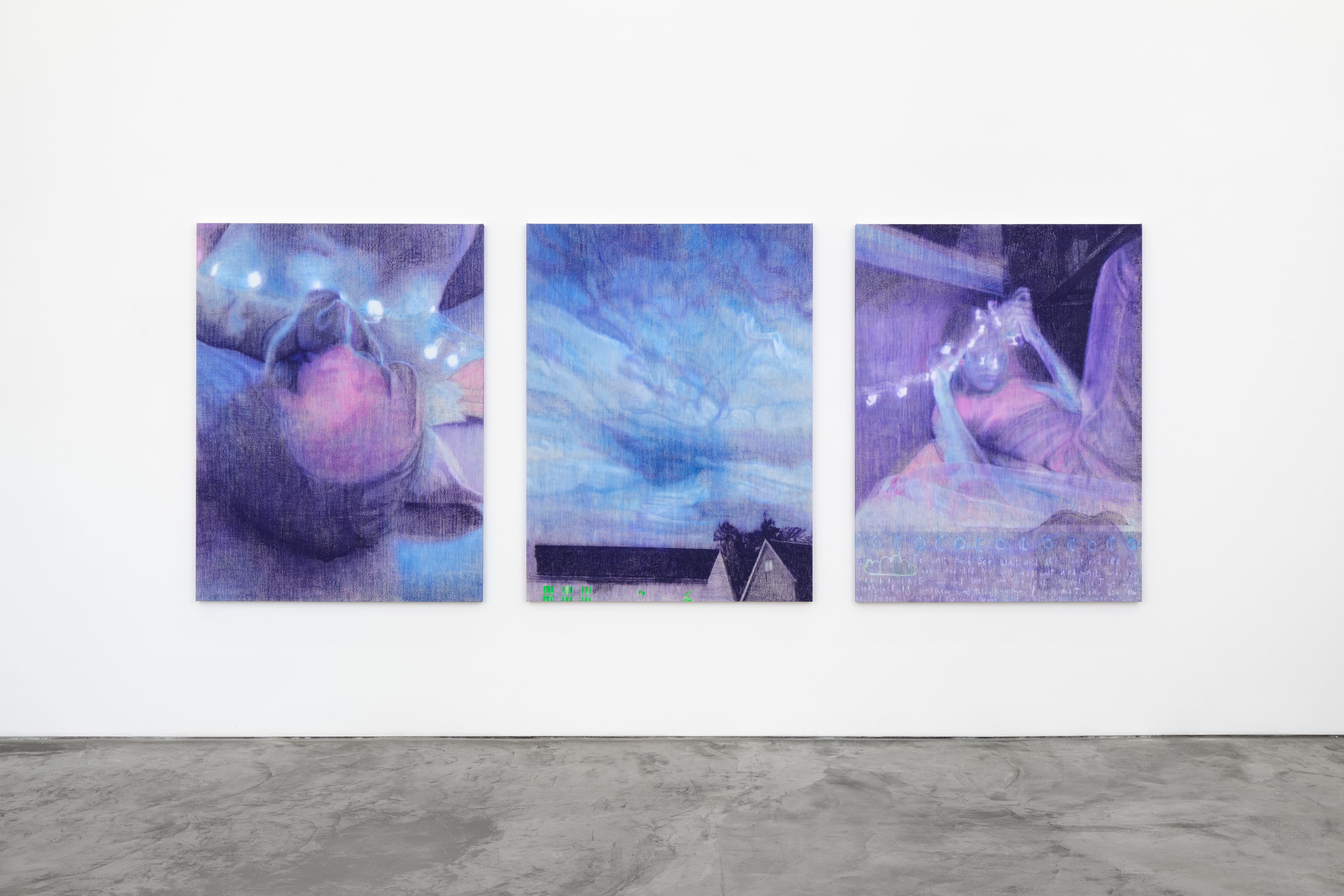

To achieve this, he scoured a forgotten age of the internet, searching through Flickr images from the early 2000s, mostly set against the backdrop of middle America between 2003 and 2007, and emulating specific pictures into ghostly, haunting collages. The colours throughout the pieces are muted and pastel, and the structures are sketch-like, bringing a mystic, piercing ambience to the exhibition that explores uber-consumerism and societal dread.

“It is very much about this yearning for a false version of the past,” he continues, fascinated by modern society’s constant inclination for a retrograde glance. “It feels like nostalgia is really present right now in general, which I’m cynical about. But at the same time, that is basically what the show is – looking at nostalgia and the darkness of nostalgia from an outside perspective. But then it is also participating in that nostalgia by depicting all these relics of consumerist culture from a pretty recent time in American history.” One image in particular proves an emblem of the wider collection: a portrait of a girl with a gun, smiling almost gleefully, with a totemic apocalyptic storm approaching behind her. “To me, that sort of sums up the feeling [about the world] right now – this general sense of despair and of fear.”

Day-Lewis created much of the exhibition on evenings spent in solitude in the Irish capital. The conjunctive process – though full of juxtaposition between the “intensely collaborative” nature of making a film and the “meditative” inward state of painting – brought an overwhelming clarity. His forays into the two disciplines are inherently linked. So much so that The Creature, an oddly beautiful silhouetted motif – originally drawn during his Art BA at Yale in the late 2010s – makes a largely unexplained but deeply impactful appearance in the film. “I’m thinking about how painting and film are bleeding together for me at the moment,” he muses. “And the way certain impulses of certain settings and images are infiltrating both for me or are constant between the two.”

It’s not just in their phonetic resemblance that Day-Lewis’s exhibition and film are interwoven. The thread of nihilism and unorthodoxy that permeates the art of Anemoia is mirrored in the dark and transgressive pits of Anemone. Mutually influenced by a German 16th-century manuscript Book of Miracles, which depicts illustrations of real and supernatural biblical events, and a monograph from photographer Nick Waplington of Sheffield in the mid-90s, the film’s visual and thematic tone is built on disparate ideas. “There’s this realism, this historical specificity in the backstory and in the setting. But then it also has these moments of magic rising to the surface. I wouldn’t say surrealism. It’s almost more like hyper-realism – where the internal currents in the characters get projected outwards. So you get these moments that feel surreal, but hopefully come from a very real, emotional substrate.”

Anemone is a slow, creeping spectacle that weaves flashes of horror, humour and fantasy into a gritty, urban tale. It follows Ray (Daniel Day-Lewis), a self-banished ex-soldier who lives an isolated existence in the moors of North Yorkshire, and the impact of his sequestered life on his brother Jem (the ever compelling Sean Bean), his previous wife Nessa (the wonderfully restrained Samantha Morton), and his son Brian (How To Have Sex breakout Samuel Bottomley). Thematically, it lives in the long-term shadow of The Troubles, with the two brothers having fought in the conflict, influenced by Ronan’s time growing up in Ireland and learning about the decades-long hostility in school.

The familial notes prove the most striking – perhaps unsurprisingly given the journey that was undertaken to bring the initial idea to life. It began as a hobby, a pastime between Ronan and Daniel. “We just started writing something together, around 2020, and at first there was no real ambition for it to really turn into anything,” the former says. It quickly came to be that whenever the two men were in the same place, they’d “just sit down at the kitchen table and write a few more pages, get to the next scene and slowly follow these characters in these scenarios we had put them in and just see where it led.”

Both upholding a fascination with the subject of brotherhood (Ronan is the middle child of three boys, whilst Daniel has two older half-brothers), it proved a bonding experience as much as a creative endeavour. But as they got closer to a fully formed story, decisions needed to be made – Daniel, ever since his latest Oscar-nominated performance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2017 period drama Phantom Thread, had declared himself retired. “It was a surprise to both of us when it became something tangible that we were both happy with and genuinely wanted to enter into this world. It was hard for either of us to deny it at that point because the script was existing as its own entity,” Ronan explains. “So it was like, ‘If we’re gonna do this, now is the time. We’ll both regret it if we don’t end up having this cosmically lucky experience of being able to work together like this.’”

Still, did the emeritus Day-Lewis take any convincing to get back in the onscreen saddle? “If there was, it was a very unspoken, gradual thing,” smiles his son coyly. “The idea for me was always for him to act in it; we just didn’t talk, I guess, explicitly about it. It’s funny because I always assumed he was going to be Ray, the main character. We were doing an interview the other day, and it turns out that he actually had originally been unsure about whether to play Ray or Jem. But over time, as we continued writing, the way we talked about it, it became increasingly certain that he was going to be Ray. It was strange. It felt like he was growing into him. I felt at times that he was really speaking as the character because we would do these improvisations as we were writing, where he would start talking as Ray and then fragments of scenes and dialogue would just appear. At a certain point, it was just, ‘Oh, okay – you’re Ray.’”

Aged 26 during the film’s production, Day-Lewis was a young debut director, plunging into the daunting task of managing a cast and crew for the first time. Did he feel ready? “I think I had thought I was ready even younger, but looking back on it, I don’t think I was,” he admits. “I had a ton of anxiety going into [the production] about being too young, often being the youngest person in the room on set. I think it meant that I had to, combined with it being my first film, really earn the trust of my collaborators.”

Those partners include the likes of composer Bobby Krlic (The Haxan Cloak) – best known for his work on Netflix series Beef and multiple Ari Aster films – as well as Love Lies Bleeding cinematographer Ben Fordesman. Hollywood heavyweight Brad Pitt is an executive producer. And then, of course, there’s Ronan’s dad.

Naturally, directing Daniel would be complex. “I think most young directors, especially a first-time director, would be extremely intimidated at the idea of giving him direction or notes, or just the actual process of working with him on set,” Ronan clarifies. “But the fact that we had written the script together was great, because it meant that we had done so much talking about the character and the emotional trajectory of the film, that by the time we got to set, there wasn’t that much that needed to be said. We had this shorthand about the character and about the world, which meant we could work pretty quietly and intuitively.”

Add in the fact that “Obviously, he’s my dad,” and the process became cathartic as well as educational. But despite their emotional intimacy, his father’s methods still remained somewhat of an enigma. “We had this level of comfort together, but his process has always been behind a curtain to me, growing up. I always had that sense of this mythic process as much as everyone else did. So it was interesting to pull the curtain back in some ways, but then in other ways, aspects of his process remained a mystery to me in a way that I wanted them to.”

Aided by Daniel’s magnetic central performance, a thunderously grungy musical soundscape and rich, operatic monologues, the film is an impressive inaugural effort. It’s imperfect and idiosyncratic but brimming with humanity and cinematic potential. Alongside the exhibition, it’ll see Ronan’s own reputation expand and acquire a fanbase to boot. How does he feel about the prospect? His father, after all, is infamously anti-fame, keeping himself – and his family – away from the spotlight as much as his job allows. “Luckily, I feel like directors can hide behind their films in a way,” Ronan says. “Even if you do gain recognition, it’s not in the way an actor does, which is something that’s comforting to me. The idea of fame is something I’m ambivalent about, and having seen my dad’s experience with it, it’s definitely something that I find scary.”

It feels unlikely that Ronan Day-Lewis will be topping box offices anytime soon – in fact, it seems like it’s the last thing he’d want to do. His is an inward and nonconformist vision, enduringly cross-disciplinary and grounded by a desire for discovery rather than glamour. He’ll naturally continue to pursue his art and his filmmaking, but would he ever follow in his father’s footsteps in front of the camera? “The idea of that is pretty terrifying to me,” he chuckles. “I think I’ll just keep on putting one foot in front of the other.”

Anemone is in UK cinemas on 7th November.

![Picture of “When We Were Developing Series [2], We Were Very Conscious Of The Live Debate About What It Means To Be British”: Tom Hiddleston On The Night Manager’s 2020s Comeback](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2Fdigsfo.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_6ReezG1f25wwuNo4gDTgLkaVyPSM)